The Real Story of John Ford's Navy on D-Day

By Tom Hogan

In his 1994 book about D-Day, historian Stephen Ambrose wrote that during the Normandy landings, Hollywood director John Ford led a team of cameramen on Omaha Beach whose job was to “take movies of everything.” As the battle raged, Ford dashed about, placing his men behind obstacles to shield them from enemy fire. Their film—most of it in color—was then sent back to London for processing but was never seen by the public. “Apparently,” said Ford, “the Government was afraid to show so many American casualties on the screen.” The Ford quotes came from a 1964 interview published in The American Legion Magazine. Ford went on to say he believed his footage had been preserved after the war. After the report appeared in Ambrose's book, historians began a decades-long hunt for the missing film. It has never been found. Now, recently discovered documents from the US National Archives shed new light on the lost film of D-Day.

A Forgotten Chapter: In 1850 a Kentucky Regiment Invaded Cuba

By Dave McCormick

By Dave McCormick

As the Kentucky Regiment entered Quintayros Plaza a Spanish sentinel called out three challenges, hearing no response from the oncoming Kentucky militiamen, he fired his weapon. This alerted the 15 soldiers defending the jail to respond with a deadly barrage, that wounded a few of the Kentuckians, including their commanding officer, Colonel Theodore O’Hara, who suffered a wound to his thigh. The Kentucky Regiment known as the Kentucky Filibusters, was a diverse mix incorporating members from all social strata: unemployed laborers, tradesmen, store clerks, lawyers, and physicians. This was a group of hale and hearty Americans, not a ragtag bunch. Of other fighting units, American and Cuban, the Kentuckians were the first to land on the shores of Cuba and performed as the van of the operation. They were the first to shed blood in in battle; their casualty rate represented one-third of the total casualty count. And these Kentuckians came close to altering the future of Cuba.

How Total War Redefined Competition and Conquest

By Mr. Shawlinski & SGM Lusiani

Total war refers to a type of warfare in which there are no limitations on the methods or means employed to ensure victory. The foundation of this concept of competition are the disregards of traditional boundaries, involving unrestricted use of weapons, targeting of territories, and engagement of combatants without distinction. In total war, the pursuit of strategic objectives often takes precedence over adherence to the established rules and conventions governing warfare, including the laws of war. The scale of destruction extends beyond military targets to impact civilian populations, infrastructure, and resources, reflecting a comprehensive mobilization of all available societal, economic, and military assets toward the war effort. This peculiar form of war has accompanied the history of humankind from the ancient times into the present day (Encyclopaedia Britannica, n.d.).

Transcontinental Convoys Contributions to Development of Army Motorization and Interstate Highway Development

By Mike Miller

Occasionally one comes across references to the 1919 Transcontinental Convoy that traveled from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco. The significance of this and surrounding events is glossed over and treated as a minor historical occurrence hardly worth note. It has a greater impact and meaning to the motorization of the U.S. Army and development of the U.S. highway system deserving more attention. The existence of what could be considered a national road system in 1919 was only notional and good paved roads between select cities existed only east of the Mississippi and in California. The rest of the rural roads in the country were graded gravel or dirt paths, at best some still only the remnants of wagon wheel ruts from western migration in the 19th century. With the introduction of the automobile, several hardy individuals and daring manufacturers dared to cross long distances in their vehicles as a challenge or to promote their products. In 1903, a single vehicle was able to make a transcontinental crossing in only 65 days.

Battle of Blue Licks

By Isaac Mounce

The Western Theater of the American Revolutionary War is an obscure topic in United States history of the period. Compared to the war in the original Thirteen Colonies, the Western. Compared to the war in the original Thirteen Colonies, the Western Theater – in what became Kentucky, Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois – is a side note. Nevertheless, the war that saw the beginning of the United States’ western expansion saw some of the most brutal scenes of the war between American settlers and British-backed Native Americans. The primary focus on the American’s expansionist ambitions was on Kentucky. Furthermore, while many Revolutionary War enthusiasts think of the Battle of Yorktown as the war’s end, Kentucky would serve as the site for the last major battle on August 19, 1782. Though small-scale by eastern theater standards, the Battle of Blue Licks went down as one of the most bloodiest and heart wrenching battles in Kentucky. However, Blue Licks turned out to be pointless victory for the Native tribes in their effort to force the settlers out of their homelands.

The Marble Man and Mac: Theories of Victory and Peninsula Campaign of 1862

By Patrick Smith

McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign could have been the decisive campaign of the American Civil War. As General-in-Chief of all Union Armies, McClellan proposed a national strategy that embraced joint and coordinated operations complementing President Lincoln’s wartime policy. His theory of victory was the product of a comprehensive understanding of both combatants, geographic and operational challenges, and tactical realities of mid-19th century war. Nevertheless, interference at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels by President Lincoln ultimately disrupted the execution of the campaign. Lincoln’s meddling was informed by a limited understanding of military operations, an impatience to end the war quickly, and goading from his political backers. As McClellan’s command was dissolved, strategic priorities changed. Operational support, muddled by military amateurs, ground the campaign to a tragic halt on the banks of the James River.

Kosovo: Sovereignty versus the Responsibility to Protect

By Jorge A. Rivera

Sovereignty is the idea that an independent state can and should govern itself without external influence or interference. The philosopher Thomas Hobbes “argued that in every true state, some person or body of persons must have the ultimate and absolute authority to declare the law; to divide this authority, he held, was essential to destroy the unity of the state” (Sovereignty, 2009, p.1). A problem then arises if a sovereign state violates international law or the natural and legal rights of its citizens within its own borders. What is the legal or moral basis for external actors to interfere in a sovereign state? For example, from 1939 to 1945, Nazi Germany systematically executed millions of Jews as a means to exterminate the Jew problem. “The Nazi trials and the 1948 Genocide Convention reflected a determination in the world community to prevent a recurrence of the Jewish Holocaust” (Sindelar, 2005). Unfortunately, cases of genocide or ethnic cleansing continue to the present day. The international community still cannot find the correct legal and moral balance to ensure the sovereignty of nations and uphold the inalienable rights of people.

Battle of Camden: False Hope

By Vernon E. Yates / Robert Shawlinski

With the fighting in the North at a stalemate during the revolt, the British needed a change and direction, this slowly begin to take shape in London. This change of policy called for the British to become more mobile and to use its littoral advantages over the rebels. The British decided that they would leave the troublesome New England Colonies for the vast plantation grounds of the South. This new strategy pushed from London came in the form of the Secretary of State for America, Lord George Germain. Lord Germain faced calls for his resignation and the prospect of falling out of favor with King George III. He had to put down the rebels’ revolt and check the rising cost of the conflict by moving South to conduct operations. This planned move to the South appeared on paper to be an excellent decision to recalibrate the British war effort. The main target would be Charleston with its deep-sea harbor for the Royal Navy and the resupply for the troops. Controlling the harbor city of Charleston also gave the British the ability to attack French interests in the Caribbean. This work will analyze the Battle of Camden and its role it played in giving false hope to the British. The lens for this analysis of the Battle of Camden will use the setting, forces, sequence of events, the battle, and conclusions. This analysis will show how the Battle of Camden gave the British “False Hope”.

A Summary of U.S Nuclear Policy World War II to SALT

By HD Bedell

United States (U.S.) nuclear policy and strategy changed dramatically in the early years following WWII. Policy evolved from the view that nuclear weapons were a powerful tool for war and policy to the view that nuclear weapons had no utility and were a Pandora's box to be isolated from all other national interests.[1] In the end, nuclear management became a strategic policy around two themes: preparation and disavowal.[2] Following Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the end of the war, nuclear weapons did not figure prominently in U.S. foreign policy. Several factors contributed: (1) Technological scarcity made them rare instruments of war; (2) the U.S. possessed a monopoly on an item with undetermined implications; and (3) the U.S. was not entirely comfortable with what it had wrought.[3] The seeds of disavowal were sown and the first fruit was the Baruch Plan.[4]

"Two Arrows Crossed" A History of U.S. Army Special Forces Branch Insignia

By Bob Seals

On June 19 1987, Department of the Army General Orders Number 35, Army Special Forces (SF) Branch, was issued. By order of General John A. Wickham, Jr., the thirtieth Army Chief of Staff, SF was “established as a basic branch of the Army effective 9 April 1987.” The insignia for the newest branch in the Army was “Two crossed arrows 3/4 inch in height and 1 3/8 inches.”[1] Originally worn in 1890 by U.S. Indian Scouts, the arrows are now on the uniforms, regimental insignia, and coat of arms for all Active Duty and National Guard SF soldiers.[2] This Army history is generally known. What is not commonly known is the story of the visionary First Lieutenant who designed the insignia, his tragic death, and the events that led to reintroduction of the arrows. This article surveys the history of Army crossed arrows including their initial use, wear, and numerous unsuccessful SF attempts to wear the arrows again before 1987. Over time, this advocacy led to the 1st SF Regiment “tribe” of Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) wearing the insignia first worn as the Indian Wars came to an end.[3]

Dangerous Liaisons: The Deadly Consequences of WWI's Alliances

By Daniel McEwen

[November, 1918] With the signing of the armistice, German soldiers, hollow-eyed with battle fatigue and hunger, abandon their trenches and begin walking home from France four long years after Kaiser Wilhelm 2nd had boastfully promised them victory there within four months. Their dirty gray columns are escorted to the German border by squads of Allied troops who follow at a prearranged distance. Victor and vanquished alike, these men are among the lucky survivors of a war that had just killed 40 million men, women and children while also triggering the most momentous reset of the global order since the Fall of Rome. Although the judgment of history is that Germany’s military leaders were most at fault in starting the war, there’s always been plenty of blame to go around.

The History of the Panzerwaffe: Volume 3: The Panzer Division

A review by Chris Buckham

Thomas Anderson's "The History of the Panzerwaffe Vol 3: The Panzer Division" is a meticulously crafted and insightful addition to the study of World War II military history. In this volume, Anderson delves into the evolution, strategies, and impact of the German Panzer divisions, shedding light on their pivotal role in shaping the course of the war. Livingston's narrative begins by setting the stage, delving into the political and military backdrop of 14th-century Europe. He skillfully navigates through the complex web of alliances, rivalries, and ambitions that shaped the events leading up to the battle. The author's ability to blend historical context with the personal stories of key figures creates a rich tapestry that engages readers from the start.

21st Century Multinational Operations at the Siege of Yorktown, 1781

By Mark R. Froom

Many authors and historians have written about the importance of the Siege (Battle) of Yorktown that led to the defeat of the British Army under Lieutenant General (LTG) Charles Cornwallis and cessation of any further military operations against the newly formed United States of America. The success of General George Washington’s Continental Army and their French allies at Yorktown played an important role in achieving American independence. This article will not analyze the tactics at the Siege of Yorktown but analyze the siege from the perspective of multinational operations. The aim of the article is to examine the operation at Yorktown through current multinational operation doctrine specifically from Joint Publication (JP) 3-16, Multinational Operations, Field Manual (FM) 3-16, The Army in Multinational Operations, and Allied Joint Publication (AJP-3), Allied Joint Doctrine for the Conduct of Operations.

Crecy: Battle of the Five Kings

A review by Chris Buckham

In "Crecy: Battle of the Five Kings," author Michael Livingston takes readers on a gripping journey through one of the most pivotal battles in medieval history. With meticulous research and a captivating writing style, Livingston masterfully reconstructs the Battle of Crecy, providing a vivid and detailed account of the clash between the English and French forces. Livingston's narrative begins by setting the stage, delving into the political and military backdrop of 14th-century Europe. He skillfully navigates through the complex web of alliances, rivalries, and ambitions that shaped the events leading up to the battle. The author's ability to blend historical context with the personal stories of key figures creates a rich tapestry that engages readers from the start.

The Contemporary Operational Environment of Afghanistan

By James F. Seifert Jr.

"Therefore, just as water retains no constant shape, so in warfare, there are no constant conditions" (Tzu, 2000, p.23). Afghanistan is a unique country that holds all terrain, from flat deserts to arduous mountain ranges. The country is sparse, with large cities and infrastructure compared to the westernized neighboring regions. The United States (US) military, along with North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) partners and allies, had occupied Afghanistan for over 20 years in the War on Terrorism. Though superior in tactics, weaponry, and personnel strength, the militaries fell victim to relentless adversaries in the region. Primitive means, with the adaptation of modernized weaponry, proved to either match or some instances, overpower the might of friendly forces. The traditional means of war with a near-peer threat did not exist as the enemy did not identify under uniforms and traditional combatant identity. For instance, the enemy identified as a farmer or shopkeeper during the day and night as a lethal force. The battlefield continually changed as time passed, as did the engagements and maneuverability of friendly forces. The US military's challenges presented by the contemporary operational environment (COE) of Afghanistan negatively affected the military's ability to fight in future large scale combat operations (LSCO).

The Battle of Gettysburg: A Synopsis

By Robert D. Wall Jr.

The beginning turning point during the American Civil War occurred between July 1st and 3rd in 1863, in and around the small town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania (PA). Historians and military leaders consider the Battle of Gettysburg the most critical engagement of the American Civil War (History.com Editors, 2009). The battle between the Army of the Potomac, Union Army (USA) led by General George Meade, and (Confederate States of America, CSA) led by General Robert E. Lee in a town 35 miles south of Harrisburg, PA would become the turning point between continued Union defeats and Confederate victories within the Potomac. Over 165,620 forces engaged during this time, with an estimated 51,112 casualties from both sides (The American Battlefield Trust, 2022). The invasion of Gettysburg was General Robert E. Lee's second attempt to invade the North with the hopes of a quick end to the Civil war. President Abraham Lincoln heavily criticized the Union Army, General Meade, for not perusing General Lee across the Potomac even though the Union Army won the battle (History.com Editors, 2009; The Lehrman Institute, 2016). Despite heavy criticism, General Meade was valid in not pursuing General Lee after winning the three-day battle at Gettysburg.

Mission Command During the Battle of Mogadishu

By Garrett D. Roberson Jr.

The Battle of Mogadishu, one of the most intense urban battles of modern times, demonstrated the crucial role of mission command in achieving success in military operations. The concept of mission command has been a cornerstone of the U.S. Army's doctrine for many years. It refers to the ability of a commander to effectively direct and coordinate their forces to accomplish assigned tasks and objectives. At the core of mission command is the idea of decentralized execution and leadership, which empowers subordinates to take disciplined initiative and make decisions within the broader framework of the commander's intent (Department of the Army [DA], 2019). This paper examines how the principles of mission command, the elements of command and control (C2), and the C2 warfighting function played a critical role in dealing with the complex and unpredictable scenarios encountered during the Battle of Mogadishu.

The Siege of Vicksburg: A Crucial Win for the Union Army

By Garrett D. Roberson Jr.

The American Civil War saw countless numbers of skirmishes, engagements, bombardments, and battles throughout its duration; however, some battles posed greater significance than others. Perhaps the most famed battle of the Civil War was Gettysburg, where the Union Army decimated the Confederate force over the first three days in July of 1863 (Reardon & Vossler, 2013). While the Union's win at Gettysburg was significant to the North's war effort, General Ulysses S. Grant won the Vicksburg Campaign during the same timeframe. The Battle of Gettysburg vastly overshadowed the Vicksburg Campaign, even though the Union Army's victory at Vicksburg played a critical role in turning the tide of the Civil War in the North's favor. Vicksburg served as an even more crucial victory for the North than Gettysburg because the Union Army cut the South's supply lines from the Mississippi River, forced the surrender of 29,000 Confederates, and ultimately broke the fighting spirit of the South.

Operation Junction City: Through the Lens of Operational Art and Design

By Jeremy C. Sims

The Vietnam War posed significant challenges to the U.S. Military, requiring a multifaceted approach in order to achieve strategic objectives. Operation Junction City, one of the largest military operations of the Vietnam War, exemplified the importance of strategic planning and coordination at the joint level (Paschall, 2016). The effectiveness of joint planning and the elements of operational art and design, utilized during the planning process proved invaluable in the operation’s success. This success hinged on the ends, ways, and means used by the joint force, identified, and assessed through the execution of friendly and enemy centers of gravity (COG), lines of operation (LOO), and lines of effort (LOE). The purpose of this paper is to offer a comprehensive analysis of joint planning and the application of the elements of operational art and design during Operation Junction City; as well as provide insight into the application of joint planning within a complex operational environment and its efficacy in achieving strategic objectives.

The South China Sea: Regional Struggle of Global Proportions

By Christopher S. Patel

China has a containment problem. Or to be more accurate, the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has numerous physical and geopolitical containment constraints that impede their ambitious goals of becoming a global economic superpower and the preeminent regional military power. The First Island Chain, an approximate line of large and small islands that starts in peninsular Southeast Asia and then runs north through the Philippines, Taiwan, and Japan (Kouretsos, 2019), is the first and most evident of these physical and geopolitical constraints. The CCP has ambitions of reclaiming Taiwan to break through part of this physical containment to their east, but that is only one small part of this containment problem. No single containment issue confronting the CCP better encapsulates physical and geopolitical constraints than the South China Sea.

Geopolitik: The Twentieth Century Perspective for Today

By HD Bedell

In the Twentieth Century, geography was an essential feature of national security, followed closely by industrial base technology and strategic resource availability. Geography, technology, and material resources were measured in exhaustive detail. However, the qualitative factors of geopolitics – territorial integrity, social and political systems, historical perspectives, and religion – were the real determinants of vital interests. Succinctly, the statisticians did not make good geopoliticians or strategists. Early Twentieth Century political geographers, in overzealous belief in the "basic tenet of nationalism"[2] – pro patria mori – "stressed the importance of geography in determining the power of a state,"[3] i.e., a state's power was derived directly from the nature of the territory it occupied.[4] Their arguments in an era of popularized science convinced followers that a state was an organological[5] entity, and that idea quickly became systemic to the major powers.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf

By James F. Seifert Jr.

During World War II, many land, sea, and air conflicts shaped the course of victories and setbacks for the United States in the Pacific region. The Navy’s Pacific Fleet endured several challenges before and during the battle consisting of command structure fluidity, land-based air forces, carrier-based air forces, and geographic force alignment changes. Toward the end of the war on the naval front, the Battle of Leyte Gulf in the Philippines punctuated the end of the Japanese naval threat (Hone, T., 2009). The battle lasted only four days, from 23-26 October 1944, off the coast of Leyte, Samar, and Mindanao islands, and claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands and hundreds of naval vessels and aircraft (Cutler, T. J., 1994). The American Navy’s effects on the Japanese naval forces ended their capacity to engage in conventional offensive operations with minimal losses to Americans (Hanson, V. D., 2017).

Mission Command: Chosin Reservoir

By James F. Seifert Jr.

"Mission command is the Army's approach to command and control that empowers subordinate decision making and decentralized execution appropriate to the situation" (Department of the Army [DA], 2019, p. 1-3). Army doctrine publication (ADP) 6-0 states that mission command relies on critical and creative thinking from subordinates that seize the initiative to develop plans and concepts to accomplish the mission (DA, 2019). Additionally, the mission command process requires leaders who understand and assume the appropriate risk levels to operations, not risk-averse or risk-tolerant. The Battle of Chosin Reservoir highlights some positive and negative takeaways of mission command from both the Chinese and American sides. The battle also spotlights where mission command and other components of mission command did not occur, causing blind spots leading to the withdrawal of United Nations (UN) forces from northern Korea.

Executive Leader Failures During the Korean War

By Jacob B. Dockery

The end of World War II led to a dramatic reduction of American military forces worldwide. While requirements to sustain soldiers in occupied countries existed, the offensive campaigns of World War II had ended, and America wanted its soldiers home. Post-World War II demobilization left the United States with a total of 590,000 soldiers, down from 1.9 million soldiers in 1946 (Longabaugh, 2014). Executive leaders continued to deliver poor strategic decisions in the Far East theater in hopes of preventing another conflict. False confidence in U.S. air superiority and nuclear deterrence led executive leaders to believe South Korea was safe from the North Korean invasion. As a result, force readiness deteriorated rapidly, and the South Korean Army and American forces with Task Force Smith were no match for the initial onslaught of North Korean and Chinese soldiers during the beginning of the Korean War.

Battle of Ia Drang

By Sgt. Maj Clayton Dos Santos, Sgt. Maj Dale J. Dukes and Mr. James Perdue

During the Vietnam War, the United States (U.S.) forces launched a bold mission in the contested region called the Ia Drang Valley.[1] Considered for many as the first major battle during the war between the U.S. Army and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), both sides showed the importance of tactics, key equipment, and capabilities to overcome an enemy in severely restricted terrain. The Battle of Ia Drang brought a clash to the confidence of U.S. Soldiers, who possessed effective fire support and close air support during operations, against a trained indigenous enemy who knew very well the terrain and was acclimatized to the weather in that region.[2] This article will explore the intent of the forces engaged in this battle, some of the important actions developed during this conflict, and the aftermath that ensued. With these topics in mind, it is relevant to first examine the historical background in order to better exploit the lessons-learned and the outcome of this battle.

An Overview of the 1944 Burma Campaign

By HD Bedell

The 1944 Burma Campaign is unique in World War II for both its aims and operations and one not frequently seen in popular WWII programming. The tragic drama, from individual survival to international political maneuvering, was played out in the seldom mentioned, but perhaps the most complex, theater of World War II – the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater.[1] The United States Army role in the CBI Theater initially was planned as a task force supporting Chinese operations.[2] Committing significant numbers of American forces was considered unnecessary due to China's vast manpower reserves, and, in addition, combat commitments in Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific meant large numbers of American troops simply were not available. The task force units assigned were logistic and training personnel based in India with supplemental liaisons stationed in China.

British Strategy in the First Anglo-Afghan Wars

By Robert F. Williams

Throughout the nineteenth century, Great Britain, the world’s preeminent naval empire, and Russia, one of the preeminent land empires, vied for control throughout Central Asia in the “Great Game.” Twice in forty years, Britain invaded Afghanistan to expand its security bubble in South Asia and prevent Russia from threatening the “crown jewel” of the British Empire—India. However, the British failure to align ways and means with a sensible political end was a critical component of this “Great Game” between the two imperial powers and led to unnecessary bloodshed. The initial invasion in 1838 was prompted by faulty assumptions about the geostrategic situation and the Anglo-Indians’ ability to pacify a politically fractured country by appointing an unpopular former leader as its head. British strategy for occupation focused on creating a strong central government in a country where power was, traditionally, local. Britain had the means to invade the country yet failed to apply its material strength to realistic political ends.

The Battle of 73 Easting

By Sgt. Maj Clayton Dos Santos

During the Gulf War, more specifically Operation Desert Storm, one of the most important tank battles in history occurred. The Battle of 73 Easting was the encounter between the United States (U.S.) 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment against the Tawakalna Division of the Iraqi Republican Guard (IRG). The Iraq armor troops were in a defensive position along the north-side grid line of the military map referred to as 73 Easting, which is from where the battle’s name is derived. The scope of the battle requires a context; therefore, it is worth analyzing the Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm events in order to better comprehend the relevance of the Battle of 73 Easting at that moment. In other words, it is important to understand the scenario and the causes that led to the outbreak of the Gulf War in 1991. It is noteworthy that several notable events took place in July 1990, days, and weeks before the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait on August 2, 1990. Baghdad was looking for opportunities to put in practice a plan to vindicate old boundaries.

Special Order 191: Ruse Of War

By Joseph Ryan

On September 5, 1862, General Lee crossed his army over the Potomac into Western Maryland. It had taken him four months to maneuver Lincoln's armies out of Virginia and the effort had left his soldiers decimated and the survivors staggering. He needed to get them into the Shenandoah Valley, the only place within a radius of sixty miles from his position, after the fierce battle at Manassas, where they could find subsistence, rest, and reorganize. But, in turning his army back from the environs of Washington, it was impossible for him to lead it directly across the Blue Ridge into the Valley. Lincoln's armies would consolidate under McClellan's command again and would either follow him or move toward Richmond, and he would have to hurry his soldiers across the wasteland of Northern Virginia to intercept them. Only one strategy would keep the enemy away from Richmond and that was to march to the Valley indirectly, through Maryland. Twelve days after General Lee's army entered Maryland, the Battle of Antietam was fought on Constitution Day. In the space of twelve hours, over five thousand young Americans lost their lives in action and another twenty thousand were wounded. Soon after, General Lee's soldiers were safely in the Shenandoah Valley, camped along the Opequon unmolested, where they remained until the end of October.

The Schlieffen Plan and a Two-Front War

By Peter Kauffner

Few plans have become famous in their own right. Alfred von Schlieffen’s plan to invade France through Belgium is an outstanding exception. Schlieffen was head of the German General Staff, the army’s planning division, from 1891 to 1906. A modified version of his plan was used when World War I broke out in August 1914. So much has been written about the plan over the years it may sound unlikely that there is anything new to say. But a great deal of fresh scholarship was published for the hundred year anniversary in 2014, including translations of the deployment plans. It is often claimed that the plan was a response to the threat of a two-front war. Yet Schlieffen’s own writing shows that this was not his motivation. The plan is better explained as an example of “cult of the offensive,” an aggressive approach to military planning that was popular in various nations at this time. Historians have long seen Schlieffen as a master technician of war, but political pressures from Kaiser Wilhelm II and others may have played a role in the development of the plan.

Raff’s Tunisian Task Force

By Carson Teuscher

Eighty years ago, inexperienced Anglo-American forces nervously waded ashore on the beaches of North Africa. The amphibious Allied landings known as Operation Torch constituted the first American combat deployment across the Atlantic in World War II. It was also the first time American and French soldiers had fought one another since the unofficial naval “Quasi-War” of 1798-1800, and, to that point in history, the largest amphibious invasion the world had ever seen.

The landings went better than anticipated. Within three days, the invasion’s task forces secured their primary objectives. Vital ports, rail infrastructure, supply depots, and roads across the Maghreb lay safely in Allied hands. Disobeying orders from Vichy, French North African military commanders agreed to help the Anglo-Americans drive the Axis from the African continent. Almost immediately, the three newly-minted allies turned their gaze east to Tunisia—a prize they hoped to capture before the enemy arrived in force.

The gambit to quickly capture Tunis would ultimately fail. Setbacks over the ensuing months tempered expectations for quick victory. Operating out of the heavily reinforced Tunis bridgehead, German and Italian mechanized units halted the anemic Allied advance in the foothills west of the city.

Eighty years ago, inexperienced Anglo-American forces nervously waded ashore on the beaches of North Africa. The amphibious Allied landings known as Operation Torch constituted the first American combat deployment across the Atlantic in World War II. It was also the first time American and French soldiers had fought one another since the unofficial naval “Quasi-War” of 1798-1800, and, to that point in history, the largest amphibious invasion the world had ever seen.

The landings went better than anticipated. Within three days, the invasion’s task forces secured their primary objectives. Vital ports, rail infrastructure, supply depots, and roads across the Maghreb lay safely in Allied hands. Disobeying orders from Vichy, French North African military commanders agreed to help the Anglo-Americans drive the Axis from the African continent. Almost immediately, the three newly-minted allies turned their gaze east to Tunisia—a prize they hoped to capture before the enemy arrived in force.

The gambit to quickly capture Tunis would ultimately fail. Setbacks over the ensuing months tempered expectations for quick victory. Operating out of the heavily reinforced Tunis bridgehead, German and Italian mechanized units halted the anemic Allied advance in the foothills west of the city.

What Lincoln’s Telegraph Can Teach Us about Wartime Adaptation

By Richard Tilley

The American Civil War was nearly over before it really began. When Union General McDowell and his 35,000 soldiers strode from Washington, D.C. southward in July 1861, they seemed destined to take Richmond. Fortunately for the Confederacy, the Virginia Central Railroad allowed last-second reinforcements to rush from the Shenandoah Valley and turn back McDowell at the First Battle of Bull Run. Two years later, another seminal invention took center stage as the rifled musket decimated Confederate General Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg, setting the stage for Confederate surrender at Appomattox by 1865. For many historians, railroads to and rifles on American battlefields fashioned modern warfare. Yet, the enduring legacy of these innovations has faded with time. The railroad was a modest improvement on the horse as a means of soldier transportation and was quickly supplanted by internal combustion and jet engines for ground and air maneuver, respectively. Similarly, rifling improved the effective range of the infantryman but no more significantly than the pike, the arrow, or the smoothbore musket and its impact pales in comparison to breach-loading and the machine gun.

Winning Empire

By Vernon Yates

The realities of empire building during the French and Indian War forced both the British and French to face the need for changes on the ground in North America. These changes required a willingness to embrace and adapt to the environment, culture, and to prosecute the war under a national strategy. This work will examine how the British were able to secure victory over the French in North America during the French and Indian War using cultural adaptation, and national strategy. The French and Indian War in North America became a by product of previous conflicts and failed peace agreement between England and France. The ability to control the fur trade and the fortunes it created became an attraction for enterprising individuals backed by trading companies scattered across North America. Tensions understandably led to conflicts between the French and British as each tried to dominate and supply the fur demand in Europe.[1]

The Battle of the Three Kings

By Comer Plummer

Morocco, August 4, 1578. Sir Thomas Stukeley, presumptive Marquis of Leinster, squinted into the sun. It was plain as a pikestaff that neither side was anxious to get under way. The day was several hours on, and the heat was already upon them. The chill of the past night, spent huddled around one of the rare campfires, seemed remote now. He tugged at his breast plate and looked out over the arid plain. It was poor land for anything, even dying. Was this the end? What an irony. He, who had evaded death alongside some of the great captains of the day, Somerset at Pinkie, Philibert at Saint Quentin, Don John at Lepanto, and a dozen lesser butchers at battlefields in Normandy, Flanders, Alsace, Scotland, and on the Rhine; he, who had courted and trumped monarchs, princes, and popes, drowning in the clutches of a lunatic boy-king!

From The Boston Store To Corregidor

By Chad Davis

In one form or another, the idiom “a yeoman’s job” pervades the anglophone world as a phrase to describe “very good, hard, and valuable work that someone does especially to support a cause, to help a team, etc.”[2] The dictionary defines a yeoman in various ways, from “a person who owns and cultivates a small farm” to “a naval petty officer who performs clerical duties.”[3] The United States (US) Naval Institute describes the enlisted yeoman rating as one of the most “enduring” to serve on our country’s Navy combat team.[4] Because nearly all types of Navy units require a yeoman, Sailors of that particular rating can be found serving in virtually any wartime scenario. Throughout World War II, one petty officer of the US Navy, Chief Yeoman Theodore Richard Brownell (1905-1990) of Fort Smith, Arkansas, served his country in ways that epitomize a yeoman’s job ― as well as another phrase associated with his home town: true grit.

The Battle of Amiens: The Beginning of the End

By Michael G. Stroud

The German offensives of Spring 1918, also known as Kaiserschlacht or the “Emperor’s Battle,” were a massive German effort to hammer the French and British allies and force an accord before the full might of the American Expeditionary Force or AEF, could be brought to bear and tip the military advantage in the Allies favor. When the Kaiserschlacht ended on 29 April 1918, over 500,000 casualties had been claimed in total from all sides, with Germany having born the largest losses with over 340,000 men. Recognizing that the German army was exhausted and depleted from constant combat, internal turmoil back home, and the breakout of the influenza, French military commander Marshal Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929) devised a strategy centered around attacks by the various Allied armies of the British, French, and Americans to reclaim the initiative.

Okinawa: Isolation or Annihilation?

By Russell Moore

The battle of Okinawa was a bloody preview of what an invasion of the Japanese home islands could look like. Okinawa was the costliest battle between US and Japanese forces in World War II. General Buckner, who led the 10th army on Okinawa, has received a mix of criticism and praise for the way he conducted the campaign. Tragically General Buckner died right before the battle ended so there was no opportunity to ask him to reflect on his command decisions during the battle. Most criticism has been focused on Buckner’s reluctance to launch flanking amphibious assaults on the entrenched Japanese troops on the southern part of the island. This forced his Army and Marine soldiers into costly frontal attack after frontal attack. His defenders say the amphibious flanking attacks were too risky and worried about an Anzio type of stalemate or worse. But was there another alternative that should have been considered? Could Buckner have considered a strategy of isolation instead of annihilation and perhaps saved the lives of thousands of US forces?

Who Will Go: Into the Son Tay POW Camp

Review by Bob Seals

November 21, 2020 marked the fiftieth anniversary of Operation IVORY COAST, the joint special operations mission to liberate American prisoners of war (POWs) held at Son Tay, northwest of Hanoi, the capital of North Vietnam. The rescue effort, launched from air bases in Thailand, was a “mission of mercy,” according to President Richard M. Nixon. The raid was also an attempt to illuminate the inhumane treatment and abuse of the POWs by their communist captors. The ad hoc Joint Contingency Task Group (JCTG) included six helicopters, handpicked U.S. Air Force airmen, and a ground assault element of fifty-six U.S. Army Special Forces (SF) soldiers, largely from the 6th and 7th SF Groups at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

The Bogeyman Cometh: The Annual Disaster

By Comer Plummer

It was toward 2030 hours on July 21, 1921, when the sun dipped behind the mountains west of Annual, ushering the end of this ruinous day. Tomorrow promised to be no better. The Spanish officers knew that they were in a precarious situation. Annual was in a cul-de-sac. According to a description of the period, the place was “an almost semicircular valley, narrow and deep, closed on all sides by towering and inaccessible mountains, except by a narrow opening that overlooks the sea."[2] There was only one route into the position from the east, through Izumar. The camp was vulnerable to fire from the surrounding heights, and its line of communication could be easily cut. The defeats of the forward and flanking outposts the previous weeks had left the Spanish camp exposed.

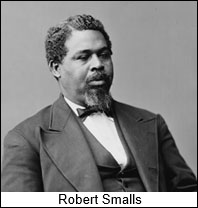

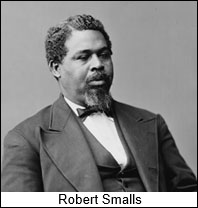

Robert Smalls: From Renegade Slave to U.S. Congressmann

By Walt Giersbach

Remarkably few people today know of the illiterate South Carolina slave who stole a warship, ran the Confederate lines to freedom and, within 10 years, had become elected to the U.S. Congress. Robert Smalls’ master knew his teenaged servant was talented, enough so that he hired the boy out in Charleston, S.C., as a longshoreman, then as rigger, sail maker, and finally wheeelman — actually a pilot in all but name only. Smalls was born in the home of his mother’s master, John H. McKee, in Beaufort, South Carolina, in1839. (Either McKee or McKee’s son may have been Smalls’ father, but this is unconfirmed).

Under Water, No One Can Hear You Scream: The loss of the submarines Argonaut, Amberjack, Grampus, and Triton January-March 1943.

By Jeffrey Cox

It takes a special kind of person to serve in a submarine. Warships and support ships are cramped enough, isolated enough when in the middle of the ocean and no land in sight, but one can at least go on deck and see the ocean, the sky, the sun. Maybe other ships. Maybe planes flying around. There is still a visible connection to the world outside the ship. On a submarine, once that boat submerges, that’s it. Your world is limited to the submarine. The control room, the torpedo rooms, the engine room, the wardroom. That’s it. There is nothing outside that metal box. Nothing you can see, unless you’re one of the lucky few to have access to the periscope. But you know there’s a mysterious undersea world outside that metal box.

Fizzling Fish and Hidebound Bureucrats: The Tragedy of the Mark XIV Torpedo in World War II

By David W. Tschanz

Fizzling fish, wrong tactics and incompetent commanders -- ingredients for disaster simmering below the waves aboard American submarines -- how many years did they add to World War II? A strong case has been made, by authors as varied as Jim Dunnigan, John Keegan and George Friedman, that the leading cause of the eventual defeat of the Japanese in World War II was the choke hold on its commercial shipping achieved by the Allies. Friedman, in his thought provoking if flawed The Coming War With Japan, argues that aerial strategic bombing had little effect on Japanese production capacity. But production capacity is useless without raw materials. US submarines, ranging on the north-south routes from the Indies and along the Japanese coast, systematically interdicted the flow of strategic materials.

Grant's Victory: How Ulysses S. Grant Won the Civil War

By Bruce Brager

Two of the great themes of the Civil War are how Lincoln found his war-winning general in Ulysses Grant and how Grant finally defeated Lee. Grant’s Victory intertwines these two threads in a grand narrative that shows how Grant made the difference in the war. At Eastern theater battlefields from Bull Run to Gettysburg, Union commanders—whom Lincoln replaced after virtually every major battle—had struggled to best Lee, either suffering embarrassing defeat or failing to follow up success. Meanwhile, in the West, Grant had been refining his art of war at places like Fort Donelson, Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga, and in early 1864, Lincoln made him general-in-chief. Arriving in the East almost deus ex machina, and immediately recognizing what his predecessors never could, Grant pressed Lee in nearly continuous battle for the next eleven months—a series of battles and sieges that ended at Appomattox.

Burn, New York, Burn! The Confederate Plot to Burn Manhattan

by Walter Giersbach

On Nov. 25. 1864, eight men walked the streets of Manhattan, New York. The group, calling themselves the Confederate Army of Manhattan, split up and approached a series of hotels on their lists and checked in. “At 17 minutes of nine the St. James Hotel was discovered to be on fire in one of the rooms,” The New York Times reported. Bedding and furniture had been saturated with an accelerant and set aflame. A few minutes later, Barnum’s Museum was ablaze. About the same time, four rooms of the St. Nicholas Hotel were ablaze. By 9:20 p.m. a room in the Lafarge House was ln flames. Then the Metropolitan House, Brandreth House, Frenche’s Hotel, the Belmont House, Wallack’s Theatre and several other buildings were on fire.

By Tom Hogan

In his 1994 book about D-Day, historian Stephen Ambrose wrote that during the Normandy landings, Hollywood director John Ford led a team of cameramen on Omaha Beach whose job was to “take movies of everything.” As the battle raged, Ford dashed about, placing his men behind obstacles to shield them from enemy fire. Their film—most of it in color—was then sent back to London for processing but was never seen by the public. “Apparently,” said Ford, “the Government was afraid to show so many American casualties on the screen.” The Ford quotes came from a 1964 interview published in The American Legion Magazine. Ford went on to say he believed his footage had been preserved after the war. After the report appeared in Ambrose's book, historians began a decades-long hunt for the missing film. It has never been found. Now, recently discovered documents from the US National Archives shed new light on the lost film of D-Day.

A Forgotten Chapter: In 1850 a Kentucky Regiment Invaded Cuba

By Dave McCormick

By Dave McCormick

As the Kentucky Regiment entered Quintayros Plaza a Spanish sentinel called out three challenges, hearing no response from the oncoming Kentucky militiamen, he fired his weapon. This alerted the 15 soldiers defending the jail to respond with a deadly barrage, that wounded a few of the Kentuckians, including their commanding officer, Colonel Theodore O’Hara, who suffered a wound to his thigh. The Kentucky Regiment known as the Kentucky Filibusters, was a diverse mix incorporating members from all social strata: unemployed laborers, tradesmen, store clerks, lawyers, and physicians. This was a group of hale and hearty Americans, not a ragtag bunch. Of other fighting units, American and Cuban, the Kentuckians were the first to land on the shores of Cuba and performed as the van of the operation. They were the first to shed blood in in battle; their casualty rate represented one-third of the total casualty count. And these Kentuckians came close to altering the future of Cuba.

How Total War Redefined Competition and Conquest

By Mr. Shawlinski & SGM Lusiani

Total war refers to a type of warfare in which there are no limitations on the methods or means employed to ensure victory. The foundation of this concept of competition are the disregards of traditional boundaries, involving unrestricted use of weapons, targeting of territories, and engagement of combatants without distinction. In total war, the pursuit of strategic objectives often takes precedence over adherence to the established rules and conventions governing warfare, including the laws of war. The scale of destruction extends beyond military targets to impact civilian populations, infrastructure, and resources, reflecting a comprehensive mobilization of all available societal, economic, and military assets toward the war effort. This peculiar form of war has accompanied the history of humankind from the ancient times into the present day (Encyclopaedia Britannica, n.d.).

Transcontinental Convoys Contributions to Development of Army Motorization and Interstate Highway Development

By Mike Miller

Occasionally one comes across references to the 1919 Transcontinental Convoy that traveled from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco. The significance of this and surrounding events is glossed over and treated as a minor historical occurrence hardly worth note. It has a greater impact and meaning to the motorization of the U.S. Army and development of the U.S. highway system deserving more attention. The existence of what could be considered a national road system in 1919 was only notional and good paved roads between select cities existed only east of the Mississippi and in California. The rest of the rural roads in the country were graded gravel or dirt paths, at best some still only the remnants of wagon wheel ruts from western migration in the 19th century. With the introduction of the automobile, several hardy individuals and daring manufacturers dared to cross long distances in their vehicles as a challenge or to promote their products. In 1903, a single vehicle was able to make a transcontinental crossing in only 65 days.

Battle of Blue Licks

By Isaac Mounce

The Western Theater of the American Revolutionary War is an obscure topic in United States history of the period. Compared to the war in the original Thirteen Colonies, the Western. Compared to the war in the original Thirteen Colonies, the Western Theater – in what became Kentucky, Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois – is a side note. Nevertheless, the war that saw the beginning of the United States’ western expansion saw some of the most brutal scenes of the war between American settlers and British-backed Native Americans. The primary focus on the American’s expansionist ambitions was on Kentucky. Furthermore, while many Revolutionary War enthusiasts think of the Battle of Yorktown as the war’s end, Kentucky would serve as the site for the last major battle on August 19, 1782. Though small-scale by eastern theater standards, the Battle of Blue Licks went down as one of the most bloodiest and heart wrenching battles in Kentucky. However, Blue Licks turned out to be pointless victory for the Native tribes in their effort to force the settlers out of their homelands.

The Marble Man and Mac: Theories of Victory and Peninsula Campaign of 1862

By Patrick Smith

McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign could have been the decisive campaign of the American Civil War. As General-in-Chief of all Union Armies, McClellan proposed a national strategy that embraced joint and coordinated operations complementing President Lincoln’s wartime policy. His theory of victory was the product of a comprehensive understanding of both combatants, geographic and operational challenges, and tactical realities of mid-19th century war. Nevertheless, interference at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels by President Lincoln ultimately disrupted the execution of the campaign. Lincoln’s meddling was informed by a limited understanding of military operations, an impatience to end the war quickly, and goading from his political backers. As McClellan’s command was dissolved, strategic priorities changed. Operational support, muddled by military amateurs, ground the campaign to a tragic halt on the banks of the James River.

Kosovo: Sovereignty versus the Responsibility to Protect

By Jorge A. Rivera

Sovereignty is the idea that an independent state can and should govern itself without external influence or interference. The philosopher Thomas Hobbes “argued that in every true state, some person or body of persons must have the ultimate and absolute authority to declare the law; to divide this authority, he held, was essential to destroy the unity of the state” (Sovereignty, 2009, p.1). A problem then arises if a sovereign state violates international law or the natural and legal rights of its citizens within its own borders. What is the legal or moral basis for external actors to interfere in a sovereign state? For example, from 1939 to 1945, Nazi Germany systematically executed millions of Jews as a means to exterminate the Jew problem. “The Nazi trials and the 1948 Genocide Convention reflected a determination in the world community to prevent a recurrence of the Jewish Holocaust” (Sindelar, 2005). Unfortunately, cases of genocide or ethnic cleansing continue to the present day. The international community still cannot find the correct legal and moral balance to ensure the sovereignty of nations and uphold the inalienable rights of people.

Battle of Camden: False Hope

By Vernon E. Yates / Robert Shawlinski

With the fighting in the North at a stalemate during the revolt, the British needed a change and direction, this slowly begin to take shape in London. This change of policy called for the British to become more mobile and to use its littoral advantages over the rebels. The British decided that they would leave the troublesome New England Colonies for the vast plantation grounds of the South. This new strategy pushed from London came in the form of the Secretary of State for America, Lord George Germain. Lord Germain faced calls for his resignation and the prospect of falling out of favor with King George III. He had to put down the rebels’ revolt and check the rising cost of the conflict by moving South to conduct operations. This planned move to the South appeared on paper to be an excellent decision to recalibrate the British war effort. The main target would be Charleston with its deep-sea harbor for the Royal Navy and the resupply for the troops. Controlling the harbor city of Charleston also gave the British the ability to attack French interests in the Caribbean. This work will analyze the Battle of Camden and its role it played in giving false hope to the British. The lens for this analysis of the Battle of Camden will use the setting, forces, sequence of events, the battle, and conclusions. This analysis will show how the Battle of Camden gave the British “False Hope”.

A Summary of U.S Nuclear Policy World War II to SALT

By HD Bedell

United States (U.S.) nuclear policy and strategy changed dramatically in the early years following WWII. Policy evolved from the view that nuclear weapons were a powerful tool for war and policy to the view that nuclear weapons had no utility and were a Pandora's box to be isolated from all other national interests.[1] In the end, nuclear management became a strategic policy around two themes: preparation and disavowal.[2] Following Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the end of the war, nuclear weapons did not figure prominently in U.S. foreign policy. Several factors contributed: (1) Technological scarcity made them rare instruments of war; (2) the U.S. possessed a monopoly on an item with undetermined implications; and (3) the U.S. was not entirely comfortable with what it had wrought.[3] The seeds of disavowal were sown and the first fruit was the Baruch Plan.[4]

"Two Arrows Crossed" A History of U.S. Army Special Forces Branch Insignia

By Bob Seals

On June 19 1987, Department of the Army General Orders Number 35, Army Special Forces (SF) Branch, was issued. By order of General John A. Wickham, Jr., the thirtieth Army Chief of Staff, SF was “established as a basic branch of the Army effective 9 April 1987.” The insignia for the newest branch in the Army was “Two crossed arrows 3/4 inch in height and 1 3/8 inches.”[1] Originally worn in 1890 by U.S. Indian Scouts, the arrows are now on the uniforms, regimental insignia, and coat of arms for all Active Duty and National Guard SF soldiers.[2] This Army history is generally known. What is not commonly known is the story of the visionary First Lieutenant who designed the insignia, his tragic death, and the events that led to reintroduction of the arrows. This article surveys the history of Army crossed arrows including their initial use, wear, and numerous unsuccessful SF attempts to wear the arrows again before 1987. Over time, this advocacy led to the 1st SF Regiment “tribe” of Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) wearing the insignia first worn as the Indian Wars came to an end.[3]

Dangerous Liaisons: The Deadly Consequences of WWI's Alliances

By Daniel McEwen

[November, 1918] With the signing of the armistice, German soldiers, hollow-eyed with battle fatigue and hunger, abandon their trenches and begin walking home from France four long years after Kaiser Wilhelm 2nd had boastfully promised them victory there within four months. Their dirty gray columns are escorted to the German border by squads of Allied troops who follow at a prearranged distance. Victor and vanquished alike, these men are among the lucky survivors of a war that had just killed 40 million men, women and children while also triggering the most momentous reset of the global order since the Fall of Rome. Although the judgment of history is that Germany’s military leaders were most at fault in starting the war, there’s always been plenty of blame to go around.

The History of the Panzerwaffe: Volume 3: The Panzer Division

A review by Chris Buckham

Thomas Anderson's "The History of the Panzerwaffe Vol 3: The Panzer Division" is a meticulously crafted and insightful addition to the study of World War II military history. In this volume, Anderson delves into the evolution, strategies, and impact of the German Panzer divisions, shedding light on their pivotal role in shaping the course of the war. Livingston's narrative begins by setting the stage, delving into the political and military backdrop of 14th-century Europe. He skillfully navigates through the complex web of alliances, rivalries, and ambitions that shaped the events leading up to the battle. The author's ability to blend historical context with the personal stories of key figures creates a rich tapestry that engages readers from the start.

21st Century Multinational Operations at the Siege of Yorktown, 1781

By Mark R. Froom

Many authors and historians have written about the importance of the Siege (Battle) of Yorktown that led to the defeat of the British Army under Lieutenant General (LTG) Charles Cornwallis and cessation of any further military operations against the newly formed United States of America. The success of General George Washington’s Continental Army and their French allies at Yorktown played an important role in achieving American independence. This article will not analyze the tactics at the Siege of Yorktown but analyze the siege from the perspective of multinational operations. The aim of the article is to examine the operation at Yorktown through current multinational operation doctrine specifically from Joint Publication (JP) 3-16, Multinational Operations, Field Manual (FM) 3-16, The Army in Multinational Operations, and Allied Joint Publication (AJP-3), Allied Joint Doctrine for the Conduct of Operations.

Crecy: Battle of the Five Kings

A review by Chris Buckham

In "Crecy: Battle of the Five Kings," author Michael Livingston takes readers on a gripping journey through one of the most pivotal battles in medieval history. With meticulous research and a captivating writing style, Livingston masterfully reconstructs the Battle of Crecy, providing a vivid and detailed account of the clash between the English and French forces. Livingston's narrative begins by setting the stage, delving into the political and military backdrop of 14th-century Europe. He skillfully navigates through the complex web of alliances, rivalries, and ambitions that shaped the events leading up to the battle. The author's ability to blend historical context with the personal stories of key figures creates a rich tapestry that engages readers from the start.

The Contemporary Operational Environment of Afghanistan

By James F. Seifert Jr.

"Therefore, just as water retains no constant shape, so in warfare, there are no constant conditions" (Tzu, 2000, p.23). Afghanistan is a unique country that holds all terrain, from flat deserts to arduous mountain ranges. The country is sparse, with large cities and infrastructure compared to the westernized neighboring regions. The United States (US) military, along with North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) partners and allies, had occupied Afghanistan for over 20 years in the War on Terrorism. Though superior in tactics, weaponry, and personnel strength, the militaries fell victim to relentless adversaries in the region. Primitive means, with the adaptation of modernized weaponry, proved to either match or some instances, overpower the might of friendly forces. The traditional means of war with a near-peer threat did not exist as the enemy did not identify under uniforms and traditional combatant identity. For instance, the enemy identified as a farmer or shopkeeper during the day and night as a lethal force. The battlefield continually changed as time passed, as did the engagements and maneuverability of friendly forces. The US military's challenges presented by the contemporary operational environment (COE) of Afghanistan negatively affected the military's ability to fight in future large scale combat operations (LSCO).

The Battle of Gettysburg: A Synopsis

By Robert D. Wall Jr.

The beginning turning point during the American Civil War occurred between July 1st and 3rd in 1863, in and around the small town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania (PA). Historians and military leaders consider the Battle of Gettysburg the most critical engagement of the American Civil War (History.com Editors, 2009). The battle between the Army of the Potomac, Union Army (USA) led by General George Meade, and (Confederate States of America, CSA) led by General Robert E. Lee in a town 35 miles south of Harrisburg, PA would become the turning point between continued Union defeats and Confederate victories within the Potomac. Over 165,620 forces engaged during this time, with an estimated 51,112 casualties from both sides (The American Battlefield Trust, 2022). The invasion of Gettysburg was General Robert E. Lee's second attempt to invade the North with the hopes of a quick end to the Civil war. President Abraham Lincoln heavily criticized the Union Army, General Meade, for not perusing General Lee across the Potomac even though the Union Army won the battle (History.com Editors, 2009; The Lehrman Institute, 2016). Despite heavy criticism, General Meade was valid in not pursuing General Lee after winning the three-day battle at Gettysburg.

Mission Command During the Battle of Mogadishu

By Garrett D. Roberson Jr.

The Battle of Mogadishu, one of the most intense urban battles of modern times, demonstrated the crucial role of mission command in achieving success in military operations. The concept of mission command has been a cornerstone of the U.S. Army's doctrine for many years. It refers to the ability of a commander to effectively direct and coordinate their forces to accomplish assigned tasks and objectives. At the core of mission command is the idea of decentralized execution and leadership, which empowers subordinates to take disciplined initiative and make decisions within the broader framework of the commander's intent (Department of the Army [DA], 2019). This paper examines how the principles of mission command, the elements of command and control (C2), and the C2 warfighting function played a critical role in dealing with the complex and unpredictable scenarios encountered during the Battle of Mogadishu.

The Siege of Vicksburg: A Crucial Win for the Union Army

By Garrett D. Roberson Jr.

The American Civil War saw countless numbers of skirmishes, engagements, bombardments, and battles throughout its duration; however, some battles posed greater significance than others. Perhaps the most famed battle of the Civil War was Gettysburg, where the Union Army decimated the Confederate force over the first three days in July of 1863 (Reardon & Vossler, 2013). While the Union's win at Gettysburg was significant to the North's war effort, General Ulysses S. Grant won the Vicksburg Campaign during the same timeframe. The Battle of Gettysburg vastly overshadowed the Vicksburg Campaign, even though the Union Army's victory at Vicksburg played a critical role in turning the tide of the Civil War in the North's favor. Vicksburg served as an even more crucial victory for the North than Gettysburg because the Union Army cut the South's supply lines from the Mississippi River, forced the surrender of 29,000 Confederates, and ultimately broke the fighting spirit of the South.

Operation Junction City: Through the Lens of Operational Art and Design

By Jeremy C. Sims

The Vietnam War posed significant challenges to the U.S. Military, requiring a multifaceted approach in order to achieve strategic objectives. Operation Junction City, one of the largest military operations of the Vietnam War, exemplified the importance of strategic planning and coordination at the joint level (Paschall, 2016). The effectiveness of joint planning and the elements of operational art and design, utilized during the planning process proved invaluable in the operation’s success. This success hinged on the ends, ways, and means used by the joint force, identified, and assessed through the execution of friendly and enemy centers of gravity (COG), lines of operation (LOO), and lines of effort (LOE). The purpose of this paper is to offer a comprehensive analysis of joint planning and the application of the elements of operational art and design during Operation Junction City; as well as provide insight into the application of joint planning within a complex operational environment and its efficacy in achieving strategic objectives.

The South China Sea: Regional Struggle of Global Proportions

By Christopher S. Patel

China has a containment problem. Or to be more accurate, the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has numerous physical and geopolitical containment constraints that impede their ambitious goals of becoming a global economic superpower and the preeminent regional military power. The First Island Chain, an approximate line of large and small islands that starts in peninsular Southeast Asia and then runs north through the Philippines, Taiwan, and Japan (Kouretsos, 2019), is the first and most evident of these physical and geopolitical constraints. The CCP has ambitions of reclaiming Taiwan to break through part of this physical containment to their east, but that is only one small part of this containment problem. No single containment issue confronting the CCP better encapsulates physical and geopolitical constraints than the South China Sea.

Geopolitik: The Twentieth Century Perspective for Today

By HD Bedell

In the Twentieth Century, geography was an essential feature of national security, followed closely by industrial base technology and strategic resource availability. Geography, technology, and material resources were measured in exhaustive detail. However, the qualitative factors of geopolitics – territorial integrity, social and political systems, historical perspectives, and religion – were the real determinants of vital interests. Succinctly, the statisticians did not make good geopoliticians or strategists. Early Twentieth Century political geographers, in overzealous belief in the "basic tenet of nationalism"[2] – pro patria mori – "stressed the importance of geography in determining the power of a state,"[3] i.e., a state's power was derived directly from the nature of the territory it occupied.[4] Their arguments in an era of popularized science convinced followers that a state was an organological[5] entity, and that idea quickly became systemic to the major powers.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf

By James F. Seifert Jr.

During World War II, many land, sea, and air conflicts shaped the course of victories and setbacks for the United States in the Pacific region. The Navy’s Pacific Fleet endured several challenges before and during the battle consisting of command structure fluidity, land-based air forces, carrier-based air forces, and geographic force alignment changes. Toward the end of the war on the naval front, the Battle of Leyte Gulf in the Philippines punctuated the end of the Japanese naval threat (Hone, T., 2009). The battle lasted only four days, from 23-26 October 1944, off the coast of Leyte, Samar, and Mindanao islands, and claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands and hundreds of naval vessels and aircraft (Cutler, T. J., 1994). The American Navy’s effects on the Japanese naval forces ended their capacity to engage in conventional offensive operations with minimal losses to Americans (Hanson, V. D., 2017).

Mission Command: Chosin Reservoir

By James F. Seifert Jr.

"Mission command is the Army's approach to command and control that empowers subordinate decision making and decentralized execution appropriate to the situation" (Department of the Army [DA], 2019, p. 1-3). Army doctrine publication (ADP) 6-0 states that mission command relies on critical and creative thinking from subordinates that seize the initiative to develop plans and concepts to accomplish the mission (DA, 2019). Additionally, the mission command process requires leaders who understand and assume the appropriate risk levels to operations, not risk-averse or risk-tolerant. The Battle of Chosin Reservoir highlights some positive and negative takeaways of mission command from both the Chinese and American sides. The battle also spotlights where mission command and other components of mission command did not occur, causing blind spots leading to the withdrawal of United Nations (UN) forces from northern Korea.

Executive Leader Failures During the Korean War

By Jacob B. Dockery

The end of World War II led to a dramatic reduction of American military forces worldwide. While requirements to sustain soldiers in occupied countries existed, the offensive campaigns of World War II had ended, and America wanted its soldiers home. Post-World War II demobilization left the United States with a total of 590,000 soldiers, down from 1.9 million soldiers in 1946 (Longabaugh, 2014). Executive leaders continued to deliver poor strategic decisions in the Far East theater in hopes of preventing another conflict. False confidence in U.S. air superiority and nuclear deterrence led executive leaders to believe South Korea was safe from the North Korean invasion. As a result, force readiness deteriorated rapidly, and the South Korean Army and American forces with Task Force Smith were no match for the initial onslaught of North Korean and Chinese soldiers during the beginning of the Korean War.

Battle of Ia Drang

By Sgt. Maj Clayton Dos Santos, Sgt. Maj Dale J. Dukes and Mr. James Perdue

During the Vietnam War, the United States (U.S.) forces launched a bold mission in the contested region called the Ia Drang Valley.[1] Considered for many as the first major battle during the war between the U.S. Army and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), both sides showed the importance of tactics, key equipment, and capabilities to overcome an enemy in severely restricted terrain. The Battle of Ia Drang brought a clash to the confidence of U.S. Soldiers, who possessed effective fire support and close air support during operations, against a trained indigenous enemy who knew very well the terrain and was acclimatized to the weather in that region.[2] This article will explore the intent of the forces engaged in this battle, some of the important actions developed during this conflict, and the aftermath that ensued. With these topics in mind, it is relevant to first examine the historical background in order to better exploit the lessons-learned and the outcome of this battle.

An Overview of the 1944 Burma Campaign

By HD Bedell

The 1944 Burma Campaign is unique in World War II for both its aims and operations and one not frequently seen in popular WWII programming. The tragic drama, from individual survival to international political maneuvering, was played out in the seldom mentioned, but perhaps the most complex, theater of World War II – the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater.[1] The United States Army role in the CBI Theater initially was planned as a task force supporting Chinese operations.[2] Committing significant numbers of American forces was considered unnecessary due to China's vast manpower reserves, and, in addition, combat commitments in Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific meant large numbers of American troops simply were not available. The task force units assigned were logistic and training personnel based in India with supplemental liaisons stationed in China.

British Strategy in the First Anglo-Afghan Wars

By Robert F. Williams

Throughout the nineteenth century, Great Britain, the world’s preeminent naval empire, and Russia, one of the preeminent land empires, vied for control throughout Central Asia in the “Great Game.” Twice in forty years, Britain invaded Afghanistan to expand its security bubble in South Asia and prevent Russia from threatening the “crown jewel” of the British Empire—India. However, the British failure to align ways and means with a sensible political end was a critical component of this “Great Game” between the two imperial powers and led to unnecessary bloodshed. The initial invasion in 1838 was prompted by faulty assumptions about the geostrategic situation and the Anglo-Indians’ ability to pacify a politically fractured country by appointing an unpopular former leader as its head. British strategy for occupation focused on creating a strong central government in a country where power was, traditionally, local. Britain had the means to invade the country yet failed to apply its material strength to realistic political ends.

The Battle of 73 Easting

By Sgt. Maj Clayton Dos Santos

During the Gulf War, more specifically Operation Desert Storm, one of the most important tank battles in history occurred. The Battle of 73 Easting was the encounter between the United States (U.S.) 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment against the Tawakalna Division of the Iraqi Republican Guard (IRG). The Iraq armor troops were in a defensive position along the north-side grid line of the military map referred to as 73 Easting, which is from where the battle’s name is derived. The scope of the battle requires a context; therefore, it is worth analyzing the Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm events in order to better comprehend the relevance of the Battle of 73 Easting at that moment. In other words, it is important to understand the scenario and the causes that led to the outbreak of the Gulf War in 1991. It is noteworthy that several notable events took place in July 1990, days, and weeks before the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait on August 2, 1990. Baghdad was looking for opportunities to put in practice a plan to vindicate old boundaries.

Special Order 191: Ruse Of War

By Joseph Ryan

On September 5, 1862, General Lee crossed his army over the Potomac into Western Maryland. It had taken him four months to maneuver Lincoln's armies out of Virginia and the effort had left his soldiers decimated and the survivors staggering. He needed to get them into the Shenandoah Valley, the only place within a radius of sixty miles from his position, after the fierce battle at Manassas, where they could find subsistence, rest, and reorganize. But, in turning his army back from the environs of Washington, it was impossible for him to lead it directly across the Blue Ridge into the Valley. Lincoln's armies would consolidate under McClellan's command again and would either follow him or move toward Richmond, and he would have to hurry his soldiers across the wasteland of Northern Virginia to intercept them. Only one strategy would keep the enemy away from Richmond and that was to march to the Valley indirectly, through Maryland. Twelve days after General Lee's army entered Maryland, the Battle of Antietam was fought on Constitution Day. In the space of twelve hours, over five thousand young Americans lost their lives in action and another twenty thousand were wounded. Soon after, General Lee's soldiers were safely in the Shenandoah Valley, camped along the Opequon unmolested, where they remained until the end of October.

The Schlieffen Plan and a Two-Front War

By Peter Kauffner