The Battle of Amiens: The Beginning of the End

By Michael G. Stroud

The German offensives of Spring 1918, also known as Kaiserschlacht or the “Emperor’s Battle,” were a massive German effort to hammer the French and British allies and force an accord before the full might of the American Expeditionary Force or AEF, could be brought to bear and tip the military advantage in the Allies favor. When the Kaiserschlacht ended on 29 April 1918, over 500,000 casualties had been claimed in total from all sides, with Germany having born the largest losses with over 340,000 men. Recognizing that the German army was exhausted and depleted from constant combat, internal turmoil back home, and the breakout of the influenza, French military commander Marshal Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929) devised a strategy centered around attacks by the various Allied armies of the British, French, and Americans to reclaim the initiative. This campaign would begin at the logistically important city of Amiens on the Somme River in northern France, which would prove to be the turning point of the entire war. This critical battle would see the implementation of lessons learned in combined arms as a way forward to victory.

Northern France and a Strategy Forward

The German gamble with the Spring offensives in 1918, while having driven into the Allied lines, did not break the Allies. Within months of the German offensives ending, the Allies had pushed the Germans back, thus negating their gains. Marshal Foch knew that the entire effort had cost the Germans dearly in material, men, and morale and with fresh American troops under John J. “Blackjack” Pershing (1860-1948) streaming into the continent, the advantage was clearly on their side. Seeking to reclaim the initiative, Foch devised a strategy not focused on concentration, but rather one of independent Allies hitting the Germans at different points along the front. The Allies enjoyed freedom of movement from within their lines in addition to a steady stream of American troops and resupply, which the Germans did not and had little to no reserves left of which to utilize.

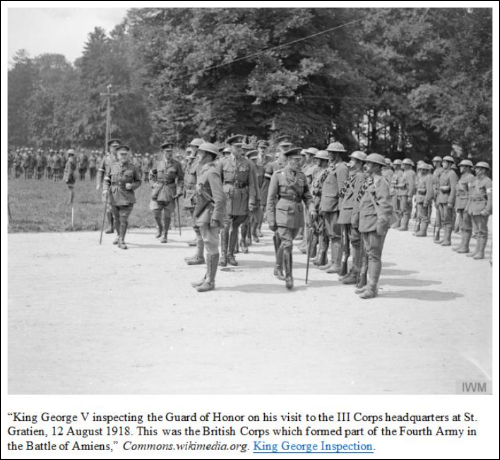

The Western Front in July of 1918 saw a dramatically exhausted, yet extremely lethal German force of 202 infantry and four cavalry divisions matched up against a similar force of 194 Allied infantry and nine cavalry divisions.[1] The Allies at this juncture however, enjoyed distinct advantages over the Germans in artillery, aircraft, and ammunition, as German manufacturing had been decimated during the war and through internal strikes and upheaval at home. Seizing upon the opportunity before him, Marshal Foch sent out orders on 28 July 1918 for the Allied army’s attack that was to begin at the city of Amiens in northern France along the Somme River. The objective of the attack at Amiens as outlined in the Foch’s orders was to “free Amiens and the Paris-Amiens railway, and to attack and push back the enemy stationed between the Somme and Avre.”[2] The attack would rely on the element of surprise or as Foch conveyed in his orders, a “covert offensive in the north via the Somme” and would include the British 4th Army under Sir Henry Rawlinson (1864-1925) and his 12 infantry and three cavalry divisions with support by the French 1st Army and their four divisions under General Marie Eugène Debeney (1864-1943).[3]

The German High Command, led by Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (1865-1937) still believed that victory was possible and ignored advice from others like Crown Prince Wilhelm Rupprecht (1869-1955) to shift to a defensive posture and to seek terms in ending the war. Though still exploring other offensive military options, the Germans by 1918 had learned some harsh lessons as to their defenses and implemented numerous measures that were in place at Amiens. The Germans at Amiens, led by General der Kavallerie Georg von der Marwitz’s (1856-1929) Second Army had implemented a layered defensive system that was intended to absorb enemy attacks and then allow them to launch strong counterattacks by position divisions.[4] This defense in depth, allowed German forces to tie up and disrupt attacking troops, which afforded counterattacks by massed divisions from beyond the range of artillery. The expectation was for these defensive divisions to hold broad fronts of between 2500-3000 meters and to buy enough time if the location was deemed important enough, for a concentrated attack by reserve divisions.[5]

The prepared German defenses were to be sorely tested as the surrounding terrain would help to dictate the battle. The River Somme ran northwards in a north-south then east west course, roughly 20 miles east from where the German lines were from their Spring 2018 offensives. The dry, flat ground here would perfectly serve the massed Tank Corps of over 200 tanks, that would include the new Mark V model, in addition to the Whippet light and supply tanks.[6] The key location of Lihons Ridge, with its nearly 360-degree view of the entire area lay further east and lorded over the railway junction at Chaulnes that was critical to the mobility of the German armies in the area. North of the Somme, the locale was more obstructed with woods and not conducive to tank operations, as were the nearby valleys. The very terrain would play a crucial role in the battle.

The Battle of Amiens: Surprise and Evolution Realized

Foch’s plan required surprise to increase its chance of success at Amiens and to achieve this, several measures were put into place. First, only the corps commanders were informed of the plan, which became exceptionally important, even as various adjustments to it were being made by Foch right up and until it began. Second, contradictory to other offensive actions in the war, there would be no pre-emptive artillery barrage followed by the infantry but rather a coordinated, rolling artillery barrage with advancing infantry. Third, the Royal Air Force would disperse smoke screens throughout the battlefield, when joined by the heavy morning mist and fog, combined for an effective screen for advancing troops.

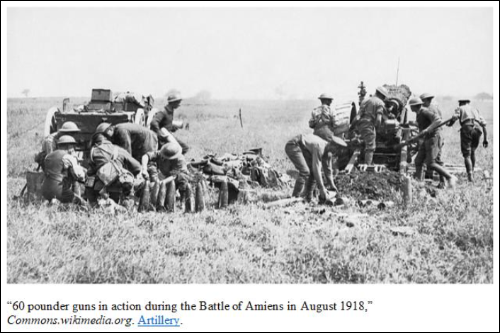

August 8th arrived with all the powerful elements of Rowlinson’s Fourth Army assembled and ready to hit the Imperial German Army. This supersized force consisted of nearly 20 divisions of British, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand troops along with three divisions of cavalry, 244 Mark V tanks (designed for crossing trenches and carried infantry gun crews), 120 supply tanks, 96 Whippet light tanks, over 3,000 heavy artillery pieces and more than 800 Royal Air Force aircraft arrayed to attack with the French south of them timed to launch their attack 45 minutes after theirs, thus keeping the Germans off balance.[7]

At 4:20 a.m. on August 8, over 3,500 British and French heavy artillery pieces opened on the unsuspecting German defenders of Amiens. The “hissing rain of shells through the air” along the 20–30-mile front was so tremendous that chaplain Frederick George Scott (1861-1944) of the 1st Canadian Division had shouted out “Glory be to God for this barrage!”[8] A combination of foggy weather and the RAF’s smoke screens did their job and helped to catch the Germans completely off guard. After a short three-minute barrage, seven Allied divisions hit the weaker six divisions of the German Second Army, along with the coordinated support of tanks which the Germans were completely unprepared for. The sudden ferocity of the Allied attack, their cover by the fog and smoke along with their artillery accuracy, shook the Germans to their core and quickly destroyed their morale.

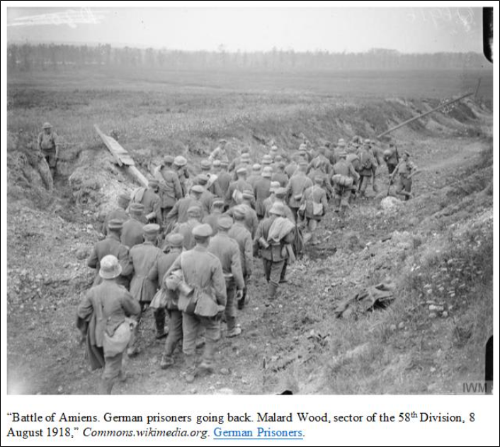

By 10:00 a.m., the B.E.F. had covered more ground than in any other time of the war up to that point. In the span of less than five hours, the Allies had surprised the Germans completely, driven them out of their defenses, while having captured thousands and having pushed six miles into enemy territory. The Allies were capturing so many Germans during the first hours of the battle, that a paper at the time, The Evening Star, reported them as “having difficulty in handling them.”[9] In fact, the Canadians would take over 5,000 prisoner and the Australians nearly 8,000 along with nearly 400 artillery pieces on that first day alone.

The advances by the Allies on the first day of the Battle of Amiens were remarkable with the Canadians having advanced eight miles, the Australians on the left flank having achieved seven miles, the French on the Canadian right advanced five miles and the British having advanced the least with just two miles due to extreme German resistance and attacks.[10] The success buoyed Allied sentiments as to the entire operation, while it was having the complete opposite effect within German circles. Official German records at the time stated that: “As the sun set on 8 August on the battlefield, the greatest defeat which the German Army had suffered since the beginning of the war was an accomplished fact. The position divisions between the Avre and the Somme which had been struck by the enemy attack were nearly annihilated.”[11]

The catastrophe of the first day would not be repeated on the second, as Gen. Marwitz had pulled reinforcements from every direction so that by the morning of 9 August, he had deployed seven new divisions in a new defensive line to face the Allied attack. As on 8 August, the attack on the 9th began at 4:20 a.m., but this time, the Germans were waiting and with regiments drawn from the 38th, 119th, and 121st Infantry Divisions, they launched heavy counterattacks throughout the entire day and into the evening.[12] The Allies, with the help of the U.S. 131st Infantry Regiment, were able to finally capture the tactically important Etinehem Spur, that now gave the Allies control of both sides of the river, along with 3,000 more German prisoners and over 70 guns. Day two had been much bloodier and with fewer gains due to a great stiffening and reinforcement of the German defenses.

Originally intending to push the battle further, Foch after consulting with his allied commanders at the scene had determined that the battle had run its course by 11 August and suspended further operations. The Allied forces were exhausted and spent in their success at Amiens, as their 13 infantry divisions and three cavalry divisions had engaged and beat 24 German divisions. The Germans had steadily changed the dynamic of the battlefield conditions, by greatly reinforcing their defensive lines with heavy artillery, pulled in 12 more divisions to brace their lines, and taken away air superiority with the arrival of German air squadrons.[13]

The success at Amiens, as was the case in most Great War battles, was costly for all sides. The Germans bore the worst of it due to the outcome of the surprise attack on 08 August, having suffered over 26,000 casualties and the loss of more than 400 guns and over 15,000 having been taken prisoner on that first day alone.[14] The total price paid by the Germans at Amiens would be more than 75,000 casualties. The Allied losses conversely were much lower than their German counterparts amounting to around 44,000 total casualties, including hundreds of tanks (through breakdowns and German guns) and around 1,000 cavalry horses. Perhaps most importantly, the psychological effect on the German military and that of Ludendorff with this defeat was significant.

Shift In Momentum; The Hundred Days

The trauma of the loss at Amiens destroyed German morale and was such a shock to Ludendorff that he recorded Amiens as “’the [second] worst experience I had to go through during the war.’”[15] His regret and breaking of the German Army at Amiens was so great that he had suggested negotiations to end the war as well as his letter of resignation to chief of staff Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934), who refused it. The Germans would remain on the defensive for the rest of the war.

The Allies at Amiens recognized that by coordinating strong assets such as air power, tanks, rolling artillery and infantry, that strong defenses could be overcome, and some semblance of battlefield mobility returned. Utilizing this general strategy beginning with Amiens, the Allies began what would become known as the Hundred Days, which would see an unbroken string of Allied victories from the British victory at Albert on 21 August to the breakthrough of the Hindenburg Line on 5 October that would culminate in the signing of the armistice agreement on 11 November 1918.

There were several valuable lessons learned that allowed for Amiens to be a victory and subsequently, the winning of the war from the quagmire that it had been the previous three years. First, the integrated use of disparate fighting platforms as part of a total force. Tanks had shown their potential at the Battle of Cambrai in late 1917 when the British used hundreds of them to punch through German defenses and overrun German trenches. Likewise, combat aircraft came into their own, having moved from the realms of just observation and signaling to strafing and bombing ground targets as part of larger offensives and in conjunction with ground units. Second, the importance of field commanders in the planning process. Though conceived by Foch in the broadest terms, it was the inclusion of those in the field like Rawlinson who used real-world intel and the situation at hand to devise and execute workable plans, such as Rawlinson’s methods of secrecy and diversions. Additionally, the importance of industrial and technological advancements, such as in artillery targeting and shells, allowed for much more battlefield precision and counter-battery fire to cut enemy communications and silence enemy guns.

The success of the Allies at Amiens owed much to two critical and important intangibles that had great effect on the battle and its outcome. The first would be that of the already flagging morale of the German army. As conditions at home worsened through political uncertainty, waning support for the war itself, food shortages and recent battlefield defeats, large portions of German soldiers and officers saw the impossibility of victory and desired peace by this point in 1918. The announcement of America having entered the war and its potential of millions of new and fresh soldiers proved too much for the average German who knew they could not stand against this tide. Second, the weather itself proved a strong enemy for the Germans the morning of 8 August. The thick fog that blanketed the area, helped to greatly conceal the coalescing Allied forces, from tanks, to infantry, to cavalry and when it was combined with the smoke screens from RAF planes, it proved disastrous to the Germans in their defensive lines.

The industrial evolution of artillery shells and ranging, the development and integrated use of tanks as a shock and break through instrument, along with ground coordinated attacks from RAF planes allowed for the Allies to both surprise and drive the Germans back farther at Amiens than at any time since the beginning of the war in 1914. The intangible yet equally important negative effects of low morale robbed the German army of its full potential at this point in war with the literal fog of war robbing it of its sight at the critical beginning of the battle, which effectively cost them the battle itself.

In the end, the Allied victory at Amiens would prove to be the catalyst for the beginning of the end for the Germans who could no longer match the material and manpower vigor of the Allies. The integrated and evolved platforms such as the tank and the airplane, along with their maneuver tactics at the Battle of Amiens restored mobility to the battlefield, while recognizing the importance of the planning and execution from the commanders in the field to achieve success. The next war would see all these factors played out on an even larger scale.

| * * * |

Show Notes

| * * * |

© 2026 Michael G. Stroud

Written by Michael Stroud. If you have questions or comments on this article, please contact Michael Stroud at: mgstroud@me.com.

About the author:

Michael G. Stroud is a passionate and dedicated military historian that researches and writes about all eras of military history from ancient to modern times. As a regular LinkedIn contributor, he contributes diverse and interesting military history pieces via websites, scholarly journals, and print magazines and his currently working on a book about England’s rise to naval supremacy. He lives in a small town in Michigan with his wife.

* Views expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily represent those of MilitaryHistoryOnline.com.