The Battle of the Three Kings: The Last Crusade

By Comer Plummer, III

Enclose me in uncertain stone

Enclose me in uncertain stone

Or in the sands of Africa

And the premature death

Of my reign is eternal war

My life is like a flame

My death seems an enigma

But whether earth and sea embrace me

Where I am is my renown.

– Crónica Del-Rey Don Sebastian, by Miguel Pereira [1]

Life I see cometh and death I presumeth

To change this life of mine into a new

Yet this my greatest comfort brings

I live and died in love of kings

And so brave Stukeley bid this world adieu. [2]

– The Ballad of Thomas Stukeley

The end of life is death.

– Arab proverb [3]

Morocco, August 4, 1578

Sir Thomas Stukeley, presumptive Marquis of Leinster, squinted into the sun. It was plain as a pikestaff that neither side was anxious to get under way. The day was several hours on, and the heat was already upon them. The chill of the past night, spent huddled around one of the rare campfires, seemed remote now.

He tugged at his breast plate and looked out over the arid plain. It was poor land for anything, even dying. Was this the end? What an irony. He, who had evaded death alongside some of the great captains of the day, Somerset at Pinkie, Philibert at Saint Quentin, Don John at Lepanto, and a dozen lesser butchers at battlefields in Normandy, Flanders, Alsace, Scotland, and on the Rhine; he, who had courted and trumped monarchs, princes, and popes, drowning in the clutches of a lunatic boy-king!

They had tried one last time to prevail upon the king. That morning, as the last of the artillery and baggage was coming across the river, the council had met. The sounds of the enemy—the pounding of drums and cymbals, the blurting horns—carried into their midst. The tension was acute. Once more, they tried to convince Sebastian to delay the attack until the afternoon. The Moroccan battle formation was now apparent, as were their numbers. They were many thousands, and there would be no bypassing them on the way to the Loukkos. Moulay Mohammad pleaded with the king to wait: The Moroccan sultan, Abdelmalek, was living his last hours!

Tom Stukeley, the seasoned campaigner of more than thirty years, knew the value of this advice, and he spoke up in support of the former sultan. Surely, he understood his countrymen best. If he judged it best to wait a few hours, then why not if it might improve their chances? He was cut off by Captain Francisco Aldaña, a Spaniard recently arrived with 500 Castilian soldiers to reinforce the army. The supercilious ass insisted that the condition of the army was such that they must attack “as soon as possible.” Stukeley tried to respond, to expose this fellow, who held himself as Ares, as nothing more than a defiler of Dutch womenfolk, but Sebastian cut him off with a familiar insult. Stukeley’s retort, purportedly recorded by a Devonshire chronicler from papers since lost, captured the essence of the moment.

| Out of your inexperience and ignorance in the stratagems of war you deem me a coward; yet this advice would provide safe and victorious, and your great haste be your overthrow; yet proceed, and when you come to action, you shall look after me, and shall see manifestly that Englishmen are no cowards! [4] |

He stormed from the tent, raging. Sebastian. He was the author of this predicament. Twenty-four-years-old, he had the disposition of a boy half that age.

He was a strange bird, Don Sebastian—doubtless a reflection of an unusual childhood. From the start, expectations weighed heavily on the king. And the hopes for this one were particularly high. Funny thing: It was a fragile state, for all the vastness and wealth of the Portuguese Empire. It extended from the African coast, east to western India, Indonesia, and China; and in the west Brazil. A nation of a million and a half people and ninety-two thousand square kilometers, the Portuguese held, directly or indirectly, an estimated four million square kilometers of territory.[5] And yet, the future of this vast imperium teetered upon the shoulders of this obstinate, tempestuous young man.

Did Sebastian grasp that he was the last hope for an independent Portugal? Did he care? He was the seventh and probably the last king of the House of Aviz, which had ruled Portugal since 1385. He was unmarried and childless, and he was likely to remain that way given his misogynistic disposition. The only alternatives of this blood line were dubious candidates: Sebastian’s great-uncle, Cardinal Henry of Évora, whom the Pope was certainly not going to release from his ecclesiastical vows to marry and sire a son, assuming the 66-year-old prelate could manage it. The other candidate was the forty-seven-year-old Antonio, the Prior of Crato, a peripheral figure of the royal family, being the illegitimate son of Louis of Portugal, Duke of Beja, the second son of King Manuel I. Should Sebastian die without an heir, the Portuguese crown would pass to Philip II of Spain. Such was mandated by a clause that Sebastian’s grandfather, King John III, had inserted into the marriage contract of his daughter, Maria Manuela, and Prince Philip of Castile (the future Philip II of Spain), whereby the crown of Portugal would pass to their offspring should he leave no legitimate heir.[6] For Portuguese nobles and laymen alike, being subsumed by Spain was the worst nightmare.

Sebastian’s upbring was likely the root of his many defects. He was, for all intents and purposes, raised as an orphan. His father, Prince John Manuel, had died of an illness 18 days before his birth. Shortly thereafter, his mother, Joanna of Spain, decamped for Madrid where she would serve as regent for her father, Emperor Charles V and later for her brother, King Philip II. Her contact with her son was limited to a few letters before her death in 1573. So, absent parental affection and guidance, Sebastian grew up training in the martial arts and steeped himself in the glories of his country’s past: the Reconquest; the exploits of Bartolomeu Dias, Pêro da Covilhã, and Vasco da Gama; the great military victories at Ceuta, Dui, and Mazagan, and the conquest of Muscat. Like most young nobles, religion figured prominently in his education. A Jesuit priest, Luis Gonçalves da Câmara, served for many years as the royal teacher, and he seems to have inspired the young man with the notion of leading a crusade against the Muslims. Naturally, Sebastian’s eye alighted upon Morocco, conveniently nearby and an easy target. Moreover, Portugal already had several footholds there, including Ceuta, Arzila, and Mazagan (present El Jadida). When I grow up,” announced the boy, “I want to conquer Africa.” [7]

In 1574, Sebastian began to put his plan into motion, That summer he snuck into the Portuguese enclave of Ceuta, in northern Morocco, where he spent several weeks at the head of a band of knights, riding hither and thither looking for a fight that never materialized. The Saadian sultan, Moulay Mohammad, was more puzzled than alarmed, and he merely order that the infidel king was to be surveilled from a comfortable distance. The experience left Sebastian convinced that the Moors would be unable to mount any serious resistance to him. He vowed to return at the head of an army to conquer the land.

Two years later, a civil war in Morocco provided the opportunity. In 1576, Moulay Abdelmalek, Moulay Mohammad’s uncle, returned from exile in Algeria and overthrew his nephew. The deposed sultan fled to the north of the country and appealed to Portuguese authorities for assistance in restoring him to power. Sebastian readily agreed, demanding in exchange several territorial concessions along the coast. Informed of his nephew’s intentions by his ambassador in Lisbon, Juan da Silva, Philip tried to dissuade his nephew from so fruitless an undertaking. Silva chimed in as well. To no avail. As the ambassador remarked in a letter to Philip, “Nothing can be done. The young man [Sebastian] pouts.” [8] At length, Philip gave up, observing succinctly, “Well, if he succeeds, we shall have a fine nephew, if he fails, a fine kingdom.” [9] He counseled Sebastian to limit his objective to the port of Larache, one of the few desirable pieces of terrain in Morocco. Above all, he warned Sebastian against a campaign in the interior of the country.

Such a modest objective did not require much of an army, but Sebastian was determined to raise a host. For months, the king toiled to cobbled together a mighty invasion force. Portugal had not fought a major land campaign in more than a century, and the preparations were chaotic. Lisbon called up its feudal army; royal commissioners conscripted thousands of troops from the peasantry; tax agents squeezed everyone, even the Church, for money. When these meager resources failed to satisfy, Sebastian widened his search. He leveraged his country to the hilt with loans guaranteed by the pepper trade; agents were dispatched far and wide in search of credit, mercenaries, and military stores. Sebastian secured the grudging support of Philip, who allowed him to recruit several thousand Spaniards as well as providing some logistical support. The last and most improbable contingent of this mongrel army was Thomas Stukeley and his contingent of 600 Italian mercenaries. The Englishman had been contracted by the Pope to invade Ireland and incite a rebellion against Elizabeth I of England. Apparently, Stukeley, the consummate opportunist, considered Sebastian’s offer of African laurels and booty a safer bet than pursuing the Holy Father’s proffered marquisate with his unruly Italians.

By the spring of 1578, seventeen thousand troops had been raised. At the heart of this patchwork group were two remnants of the chivalric age. The first, the Aventuros, was an elite unit of fifteen hundred gentlemen volunteers who made a hobby of the military arts and served at their own expense. Their élan usually earned them a place of significance on the battlefield, where their example might inspire the rest of the army. Alvaro Pires de Tavora, brother of Christovão, was in command of this group, with John Alvarez de Azevedo and Pedro de Lopez as his sergeants-major. The second was the encubertados, or heavy cavalry, which consisted of nobles recruited from the finest families of the land, numbering about one thousand, and divided into two squadrons, one commanded by the Duke of Aviero, the other by the king.

The main body of the army was tercio regiments. Introduced in 1534, the tercio, or Spanish Square, was the last word on the Greek phalanx, the self-contained infantry formation designed for repelling a mounted foe in the defense and for shock effect in the offense. The tercio was an innovation of early combined arms warfare, employing traditional infantry weapons with modern firearms in mutually supporting roles.

As its name implied, the tercio (third) was, generally speaking, composed of an equal ratio of pikemen, swordsmen, and musketeers or arquebusiers; it was also typically deployed in a regiment of three brigades, each commanded by a colonel. It was a block formation consisting of a hollow square of pikemen up to twenty ranks deep, swordsmen on the inside, and men bearing firearms massed at the corners, or “sleeves,” where they could achieve interlocking fires with adjacent formations. Sometimes halberdiers were interspersed with the pikemen for added carving power. The idea was mutual support. The pikemen protected the musketeers/ arquebusiers from cavalry that might otherwise, due to the slow reloading rate of early firearms, sweep them from the field, and firearms protected the pikemen from the enemy’s mounted musketeers/ arquebusiers. The swordsmen were for close-quarter combat. It all worked very neatly, at least when practiced by experienced Spanish soldiery.[10]

Whether such tactics were appropriate for warfare in the Barbary was not much considered. A few old frontieros, knights experienced in the peculiarities of the terrain and tactics in this theater, favored an army that emphasized light cavalry and mobility. They were overruled. Sebastian insisted on a conventional, infantry-heavy approach, with a modest arm of heavy cavalry.[11]

The tercio constituted the bulk of the army, some fifteen thousand Portuguese levies and foreign troops. These homas d’armas included the nine thousand Portuguese conscripts (of which five hundred were engineers) and fifty-five hundred foreign troops, Germans, Castilians, and Italians. Probably half were espingardeiros equipped with either the arquebus or the musket, and the rest were mostly pikemen. Rounding out the army was an artillery component of perhaps two hundred or more bombardieros and thirty-six cannon of various caliber, commanded by Pedro de Mesquista, a knight of Malta.[12] Not counted in these numbers were the sailors of the fleet of several hundred ships—galleons, galleys, and supply vessels—being readied under the command of Don Diogo de Sousa.

Accompanying this expedition was a second army. Nobles vied with one another in the elaborateness of their field camps, each of which required a number of servants. This strained the army’s transport to the degree that eventually the king was obliged to impose a limit of six servants upon each noble (subsequently, an exception was made for the Duke of Bragance, who was permitted nine). Apparently, the restriction was easily bypassed, since some managed to bring along as many as fifty servants. In all, at least 9,000 noncombatants were on hand—footmen, cooks, bakers, “wagon drivers, with an infinite multitude of pages, lackeys, servants, mule drivers, and women to serve, and a large multitude of women of pleasure.” Some two hundred children tagged along. Hundreds of clergymen were included to minister the spiritual needs of the army and to convert the conquered land to Christianity, including Alexandro Formento, the papal nuncio.[13]

The fleet—or most of it—departed Lisbon on June 26 and continued to Cadiz where it awaited the arrival of additional Spanish troops and supplies. Logistical problems and weather delayed the departure until July 14. All the while, the troops remained aboard their ships, consuming their limited foodstuffs and fresh water. By this time the last ships of the fleet had finally caught up. Silva, Philip’s eyes and ears on the expedition, caustically summed up this first phase of the operation when he wrote to his king, “We’ve been beating around the bush for eighteen days because His Majesty did not want to wait three or four days at Lisbon in order to raise anchor with his entire fleet; if we had left Lisbon with all our men, in four days we could have been [in Morocco]…and we are already running low of everything.”[14]

The fleet finally arrived at Arzila on July 12. This small port settlement thirty kilometers north of Larache, was to be the staging area for the operation.[15] The Portuguese had abandoned the place years earlier, and it was not hard to see why. It had no particular economic or military advantage. The small bay offered poor anchorage for ships, and the fort was of the traditional stone masonry type with a proximity to the foothills that made it vulnerable to landward attack.

The chaotic debarkation at Arzila revealed the poor state of readiness of the army. Units intermingled on the beach, and men bivouacked where they pleased, only to be told to relocate time and time again as senior officers sparred over the terrain. Cavalry horses, transport animals, cows, and sheep added to the confusion. That day and the next, rough seas hampered the off-loading of food supplies, and men went hungry or scavenged in the brush. The Portuguese disdained the inconvenience of erecting a contiguous defensive barrier around their bivouac. In a few places earthworks were prepared; in most others, wagons were interspersed with the terrain to form a barrier; in some sectors sentinels alone protected the camp as they slept off the wine. One night when Stukeley was out inspecting the guard, one of his Italian sentries fired upon him. The night must have been particularly dark, or perhaps Thomas simply lost his way in the hilly terrain. The captain’s oath was still in the air when the tents erupted. A mass exodus ensued. The Moors, they bellowed, were sweeping through the camp! Thousands of panicked recruits descended, half naked, roaring to the heavens, down to the beach in search of boats to carry them to the safety of the fleet in the harbor. Silva observed, “There was an extreme confusion, no man knew what he had to do or where to go, to such an extent that, if there had been an enemy, he could have brought about a terrible massacre without loss to himself.”[16]

Certainly, the troops were poorly trained. History does not record any maneuvers conducted prior to embarkation, but given the dispersion of the national components around Lisbon, it is doubtful that such took place. Individual training was also deficient. In many cases, firearms were issue to troops just prior to ship boarding. Many did not receive their weapons until they arrived in Morocco. Aldaña’s 500 Castilians did not receive any firearms, as it was (wrongfully) assumed they would be supplied in Africa. This allowed for little marksmanship training. The tercio formation placed special demands up the army. Handling a pike posed a number of challenges for the conscripts, not the least of which was physical. At between three and seven meters long, and weighting up to ten kilograms, the pike was notoriously hard to handle and required training and stamina. And the weapon was designed to be used en masse, which meant in tight quarters (the Swiss were known to pack three thousand men into a sixty-meter square formation) and in unison with others. In addition to their lackluster training, these underfed and sickly troops were probably in no physical condition to wield the pike. As one of the expedition’s chroniclers, Luis Nieto described:

| Most of these troops were in great difficulty, and suffered many illnesses and hunger; when their food started to lack, being so parsimoniously distributed that several died of hunger, which was the fault of the officers, who very often are the cause of the failure of Princes and generals in similar misfortunes and needs. And to top it off, the majority of the soldiers had no knowledge of the military arts, having never experienced war.[17] |

A misguided operational plan compounded these faulty preparations. According to Spanish chronicler Luis de Oxeda, Moulay Mohammad, echoing King Philip’s advice, broached a sensible strategy, beginning with a land-sea assault on Larache. This, he maintained, must succeed given the Portuguese naval dominance and the poor state of the city’s defenses. Sebastian would fortify the place and remain there with the bulk of his army while Moulay Mohammad would lead a joint thrust inland to Ksar el-Kébir, a fortress town some thirty kilometers farther down the banks of the Loukkos River. He expected that many tribes would defect to his side, and such would permit further advances inland. Should this not occur, then Moulay Mohammad would retire to Larache, and they could consider a future course of action. Sebastian dismissed this advice out of hand. He not about to let the glory go to his Moorish supplicant.[18]

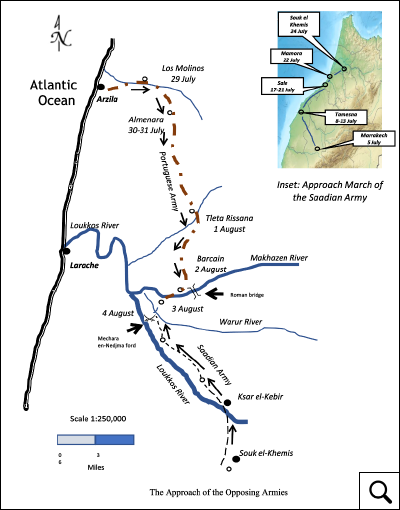

At a final war council on July 27, the king announced his plan. The army would advance southeast some forty kilometers to capture Ksar el-Kébir, destroying the enemy’s army should he give battle. It would then cross the Loukkos at the Mechara en-Nedjma ford, follow the river west to Larache, and attack that city from the south bank. Two thousand soldiers would remain with the fleet, which would sail to meet them at the final objective. Six days’ rations, the anticipated duration of the operation, were to be distributed to the men. July 29 was fixed as the date of departure.

Few of Sebastian’s commanders were thrilled with this plan, surrendering as it did their one clear advantage—the fleet. The experienced officers, including the commanders of the various foreign contingents, Stukeley (the Italians), Martin of Burgundy (the Germans), and Alfonso de Aguilar (the Spanish), knew the army was not a cohesive force and, crucially, it lacked a general-in-chief to lead it in battle. Furthermore, given the nature of the terrain and the need for mobility, Sebastian’s insistence upon taking all the baggage and noncombatants along was, to many officers, incomprehensible. Stukeley was beside himself: Why not leave all the impedimenta at Arzila and send it on to Larache once that place had been taken? No more eloquent description of this unhappy situation came from the plume of Juan da Silva, who continued to pour out his anxieties to Philip, this time on the eve of the advance:

| I cannot depict in a complete manner to Your Majesty the difficulties that assail us. But one must consider how few we are for such an adventure; the soldiers are inexperienced, undisciplined, poorly commanded, and without any leader but the King, whom, by his excessive temerity took from the army any courage it might have had and filled it with fear. Finally, not an officer ventures to contradict the King, and all are sure he leads them to a certain death.[19] |

In contrast, the Saadian army preparations went along smoothly. Spies kept Abdelmalek well informed of Portuguese intentions and plans, and he moved with alacrity to receive them. While the Christian army was massing in Lisbon, The sultan and his brother were assembling the regular forces of the army and incorporating tribal augmentees; transport animals and supplies were collected from the cantons; and Larache was reinforced for an expected siege. On July 5, as the Portuguese were dithering at Cadiz, Moulay Abdelmalek began to move north from Marrakech with an army of 14,000 horse, 2,000 arquebusiers, and 26 cannon. From Fez his brother, Moulay Ahmad, led another 22,000 horse and 5,500 arquebusiers to join with them at Salé. They would move from there east to Ksar el-Kébir in order to block any Portuguese advance into the interior.

Unbeknownst to the Portuguese, the Saadian army had become capable of fighting a set-piece battle. Since the inception of the dynasty (1549), Saadian sultans had prized artillery; they developed foundries and various calibers of guns. Abdelmalek continued this work, developing mobile factories where cannon could be forged near the battlefield to lessen the need of transporting heavy guns across Morocco’s many mountain ranges and ravines.[20] Furthermore, Abdelmalek knew the value of professional soldiery. During his exile, he had served with Ottoman forces at the Battle of Lepanto (1571) and during the Second Siege of Tunis (1574). Abdelmalek had seen what skilled forces like the janissaries could do, and he was determined to develop a cohort of infantry and leave behind the traditional equestrian, hit-and-run tactics that was the hallmark of Moroccan warfare. He recruited and trained salaried professional soldiers, including a artillerymen and a legion of Andalusian infantry arquebusiers.

Unfortunately for the Moroccans, a major complication arose on or about July 10, when Abdelmalek fell violently ill while moving north with his army. He began to experience violent fits of vomiting and ague, or alternating chills and fevers. He had a raging thirst but was able to eat very little and was unable to hold down any meat. He began to lose weight and strength at an alarming rate.[21] By the time the army arrived at Ksar el-Kébir the sultan was traveling in a covered litter, his condition a carefully guarded secret, known only to his closest advisors, his doctor, Joseph Valencia, and his chamberlain, Ridwan.

Speculation has long surrounded the cause of this malady. The prevailing theory of the time was that the sultan had been poisoned, but the evidence is scant xxii Whether by an attempted assassination or illness, the eve of battle found the sultan at death’s door. On August 4, an eyewitness, Luis Nieto, described the sultan as “yellow” in color, suggesting jaundice characteristic of sepsis and multiorgan failure.[23]

On June 29, the Christian forces finally moved out of Arzila. It was a curious affair, almost comic, with the nobles riding in gilded carriages accompanied by the musings of minstrels and musicians; bringing up the rear was a baggage train must have extended hundreds of meters to the rear, with its multitude of wagons and rolling pavilions, as well as numerous transport animals. As many as 1,120 wagons were required just to transport the baggage of the nobles.xxiv Other than a few carts for munitions, the army’s transport was devoted solely to this purpose. Walking and riding in and alongside the train were thousands of noncombatants. It was more the look of an evacuation than of an invasion.

The mob managed just five kilometers on the first day; by the end of the second day—another five kilometer slog—the king and his commanders were contemplating a return to Arzila, such was the condition of the army. At this point, it was not about training, but the basic equipment and physical condition of the troops. To begin with, body armor was a problem in this environment. Few nobles donned the cap à pied of olden times, but prestige still influenced the wearing of more steel skin than was good for a man. Cavalrymen had it best, for mobility required a lighter kit—breast and back plates and chain mail skirt—and, of course, they rode. Arquebusiers were also generally less armored, but the pikemen suffered not just the torso armor, but also the steel scales for the shoulders (pauldrons) and for the thighs (tassets). All wore the peaked morion helmet. Marching in such attire, and porting a load of nearly nineteen kilograms, including armor, clumsy weapons, ammunition, powder, rations, a three-liter gourd, and such, was difficult enough in Europe, where there were roads. Here, there was only broken ground.

The hunger was another, more pressing issue. After only two days, many troops had consumed half of their rations.[25] There were obviously no food reserves since the wagons were for the nobles’ baggage and artillery munitions. Of all the signs of Portuguese ignorance in campaigning, this ineptitude at the most elemental level of logistical planning was perhaps the most telling.

Nevertheless, the march continued. The heat and shortage of food began to take a serious toll, and many soldiers jettisoned their arms and equipment and lagged behind, swelling the already bloated tail. The army left in its wake pieces of armor, pikes, empty bottles and haversacks, furniture, carpets, and just about everything imaginable. Most of the artillery wagons had broken down, their loads abandoned.

On Saturday, August 2, the Saadian army advanced past Ksar el-Kébir and camped northwest of that town. The sultan’s forces now sat astride the wide Loukkos alluvial plain that stretched the thirty kilometers between this town and Larache. To the front was agricultural land, baked khaki in the summer heat, broken by a small river, the Warur. Several kilometers farther on ran a larger tributary of the Loukkos, the Makhazen River, and beyond it the hills that concealed the invaders. To the right, the Gharb’s elevations rose up in a series of low ridgelines. On the left were the serpentine Loukkous and the Mechara en-Nedjma ford. It was precisely what Abdelmalek had envisioned and ideal terrain for a cavalry-heavy army.

That same day, the Portuguese army covered ten kilometers, passing though the modern-day Rissana district around a squat, ten-kilometer-long ridge, whose center was pierced by the Makhazen River. There they intended to pass into the gap and cross an old Roman bridge, located near the modern village of El-Adeb, and then continue south to Ksar el-Kébir. Finding the bridge defended by about two thousand horsemen, the king determined not to attack and to continue along the north bank of the Makhazen to a ford Moulay Mohammad’s men told him was a few kilometers farther down river. Arriving at this location late in the afternoon, the Portuguese army camped at a place they called Barcain and prepared to cross the following morning. The opposing armies were now on a collision course.[26]

At camp that evening, the king again convoked his war council. The look on their faces said it all. The unwashed Don Duarte de Meneses, the governor of Tangiers and the master of the general camp; Antonio, Prior of Crato, the dandy no more; Jorge de Lencastre, the Duke of Aviero, watery eyed and completely fagged out; the twelve-year-old boy, Duke of Barcellos, designated to replace his ailing father, the Duke of Bragance, looking scared; the Count of Vimioso and Jean Lobo, Baron of Alvito, sitting cross-armed and shoulder to shoulder, glowering at the subdued the royal favorite, Christovão de Tavora; Pedro de Mesquita, the old knight of Malta, now every bit as glum as Moulay Mohammad; the foul-mouthed Alfonso de Noroña, Count of Mira; the priests and their thin smiles. The carnival was over.

Defeat. Thomas Stukeley had seen it before. Its signs were everywhere and plain enough to the enemy. Their route of march was a field of litter, and the best efforts of the sergeants barely slowed the leak. When they made camp, it was more of a collapse. Men dropped where they stood. A few tents went up, but for the most part the pavilions stayed on their carts. The enemy had but to block their advance and starve them into submission. How the king and his cronies had made a pig’s ear of everything. Only now did these saltwater Caesars grasp the nature of land warfare. Only now did they see all the senseless, useless impedimenta!

The conversation was lively that night, and Sebastian, as usual, had the last word. True to form, of the tactical options discussed, he chose the more hazardous one. The good news for all was that the march to Ksar el-Kébir was definitively off. They would pull up several kilometers short of that former objective, cross the Makhazen and onto the Loukkos plain, give battle if offered, and continue to the Mechara en-Nedjma ford. Once across the Loukkos, they would follow the river to Larache. For the king it was the more honorable course of action. It also offered the hope of a decisive battle.

The army crossed the Makhzen unmolested on August 3, leaving the artillerymen and engineers to haul the remaining guns across at low tide. Meneses sent a scouting party ahead, and they soon returned with news that the enemy had been observed on the high ground beyond the Warur River, tributary of Loukkos. Sebastian halted the army at dusk, and they camped in a cul-de-sac on the plain between the Warur and Makhazen.

The dawn of August 4 revealed a quiet scene. Neither side was in a hurry to fight. The Moors watched and waited as the Portuguese hauled their artillery across the Makhazen and deployed their forces. To confront the enemy host lying off their left flank, the Portuguese army angled southeast, toward the high ground.[27] The sergeants moved down the formations, barking orders, checking equipment, and dressing the lines. The rank and file meekly complied. Row by row, the men settled into place, everything orderly, or as best as could be expected. The pikes were held upright and free hands that were not shielding eyes from the glare peeking over the hills kept busy arranging kit, checking some last detail, wiping brows, and swiping at flies.

The sultan’s doctor, Joseph Valencia, recorded that the sultan rose before sunrise in encouraging form. [28] He was in good spirits and, most importantly, it seemed as though his appetite was returning. For breakfast he had a bit of soup and three eggs; a few hours later he ate a meal of chicken and bread. Learning of the Christian army’s advance, Abdelmalek had himself dressed in his parade attire: a gold kaftan embroidered with foliage, a plumed turban decorated with a medallion setting of three precious stones, his prized sword that was a gift of the Turks, and a dagger, both encrusted in fine stones and pearls.[29] While Valencia looked on disapprovingly, the sultan rode out under his crimson and gold parasol to inspect the disposition of his forces. Returning to his command post, he spoke briefly with his principal commanders, offering words of encouragement and promises of recompense for brave deeds done this day. When the officers rode off to rejoin their units, attendants raised the sultan’s kaftan and untied him from his saddle. Exhausted, he returned to his litter to await the battle.

When at last all was in position and Sebastian had emerged from his tent, the sun was already blazing through the cloudless sky. The king, sporting the tabard of Saint Louis over his breast plate, climbed into his gilded coach and rode a short distance to a position before the army. Rattling along behind him were the carriages of the high nobles, mostly obscured in breakers of dust. The king was first to swing into the saddle, atop the white charger that had been held in readiness since first light. The nobles scurried to join him, staggering and coughing through the powdery air, and shaking off the hasty brushings of footmen. Even with the layer of grit, the medieval finery was exceptional by any standard—a greater display of chivalric pageantry than in any tilt yard.

The king rode down the lines, with the standard of the House of Aviz in tow, exhorting his troops to conquer or die for the cross, and admonishing potential shirkers that neither the enemy nor God would show them any mercy. Despite their thousand miseries, many men honed in, trying to believe, striving for inspiration. The group then proceeded to an open-air chapel for a final religious service. The long crucifixes head high for all to see, the bishops of Coimbra and Oporto led them in prayer, and a solemn benediction for the coming victory.[30] Along the battle lines, dozens of priests circulated among pensive veterans and trembling recruits, offering a more humble appeal.

At ten o’clock, the Portuguese army began to advance toward the Loukkos and the waiting Saadian army.

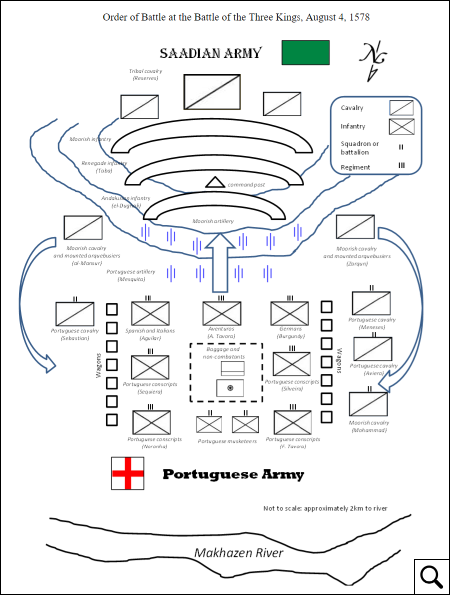

The army’s formation was a giant moving square, built around the thousands of noncombatants and the baggage that the king would not leave behind. The square was probably about eight hundred meters across and about five ranks deep. It was hardly the density of a tercio, but, given the situation, it was the best of few options. And, if a bit on the unconventional side, the concept had worked before, albeit on a smaller scale. The Portuguese, however, had no experience in fighting such a formation. Even the Swiss would have been hard-pressed to conduct an attack in a tactical pattern they had never rehearsed. Had the Portuguese done so, they might have appreciated how the success of such a formation depended on maintaining the integrity of the square against a more numerous and mobile foe.

The artillery was out front, what of it that remained. Thirty-six pieces had left Arzila, but most had been abandoned on the march or could not be muscled across the Makhazen ford in time. Now, at the crucial moment, Pedro de Mesquita’s command was reduced to perhaps as few as six pieces.[31] Next came the advance guard, consisting of the best troops—the Italian and the Castilian regiments on the left, under Alfonso de Aguilar, the Aventuros in the center, commanded by Alvaro Pires de Tavora, and the Germans of Martin of Burgundy on the right.[32] As the tercio required, the troops along the line were armed with the pike, with arquebusiers massed at the corners to protect the flanks of each regiment.

The main body followed: five regiments of troops that formed the left, right, and rear of the square. Each flank was secured by two regiments of Portuguese infantry, the left units commanded by Diogo Lopez de Sequeira and Miguel de Noronha, and those of the right by Vasco de Silveira and Francisco de Tavora. These troops were shielded from cavalry charges by a long line of wagons, reinforced by arquebusiers, deployed in column on both sides of the square. The rear guard was provided by two battalions of musketeers. Inside the square churned the baggage train—a chaotic throng of men, beasts, and wagons that must have covered several acres. The 500 unarmed Castilians were somewhere among them. Half of the army’s strength and most of its firearms were assigned to a purely defensive role. No forces could be spared for a reserve.

The cavalry was deployed forward on both flanks of the army. On the left was a force of some six hundred horsemen under Sebastian, and on the right were three detachments, those of Duarte de Meneses (400 Tangiers cavalry), the Duke of Aviero (300 horsemen), and behind them Moulay Mohammad’s contingent of 500 Moorish cavalry and mounted arquebusiers. This latter group lagged back, as the speculation would follow, to be in a better position to escape if necessary.[33]

An anxious hour’s march brought the armies into range. The Portuguese stopped, unlimbered their artillery, and tightened up the square. Sergeants dressed the ranks and steadied the quaking. Both sides studied the other. The Moors wondered at the strange formation. Surveying the long line of cavalry, the Portuguese asked themselves just how deep the Moorish ranks were—they were plainly long enough to envelop them. And a surprise: before the sultan’s standards, now clearly visible near the base of the hill, was a neatly dressed mass of infantry.

The musical cacophony was much louder now. A few Moorish musicians and soldiers whose job it was to create this ruckus cavorted up and down their lines, blowing horns and banging percussion instruments, sometimes pausing to make lewd gestures. The mass of Moorish soldiers joined in the act with uncoordinated, undulating chants that blended into a steady hum. Christian hearts hardened before this display. The footsore, dispirited, hungry men, caked in filth, suddenly felt mocked. It seemed the culminating injury. Finally, their blood was up and their hate redirected.

Looking on from the Moorish artillery, another eyewitness, Vincent LeBlanc, described the Loukkos plain. “Twas,” he wrote, “in a field above two leagues every way without either tree or stone.”xxxiv It was hot, the hottest month of the year, with daytime temperatures climbing into the mid-30 degrees Celsius (mid-90 degrees Fahrenheit). And the sun was in the eyes of the Christian soldiers. All the same, they did not know which was worse, to stand under the blazing sun, wilting in their armor, or the endless marching, more like staggering, over the infernal ground. They were disheveled, gaunt from hunger and fatigue, faces streaked with the trail, stains of perspiration showing through the missing bits of armor. The nobles tried to put up a good show, and they suffered for it. Even Sebastian was showing his mortality, his saddle wet from the water pages poured under his armor to keep him from overheating.

For a long moment the armies faced one another stoically, as if on parade. Then the Moorish artillery fired a salvo, a shuddering, eardrum-shattering emission that jolted men and beast alike along the battle lines. Nieto dramatized the initial moments of the battle accordingly:

| The Moors were the first to fire their cannon. They had not fired a third shot before the Christians responded, and the arquebuses of both sides rained like hail, with a terrible furor and horror and fright, that it seemed as if the earth would split apart for the quaking of this hideous cannonade, and the sky would alight for the fire and lighting and thunder of the artillery.[35] |

After a few salvos, the artillery fire slacked and then died, the guns disappearing into the lead ranks as the advance guards of both armies moved forward to engage one another with bullet and arrow. The Muslims had more of both, and Christians were getting the worst of it. The Aventuros became restless for the order to charge. Aldaña grew fidgety, his gaze shifting back and forth. He shouted at the king to give the order. Sebastian was probably mesmerized by his first combat, the sights and sounds, the sheer magnitude of it all. As if awakened, he at last signaled the advance guard to attack. It was the only order he would give the army.

Cries of “Aviz e Christo” and “Bismillah” filled the air as the infantry battle got under way. The Christian vanguard advanced in disciplined cadence, lowering their pikes as they drew near the enemy lines. The pace quickened. The Muslim arquebusiers volleyed and shook the oncoming lines, but the slowness of reloading allowed the Portuguese to close. The Aventuros’ impetuous reputation did not fail, and they outpaced the Castilians and Germans in leading the charge into the Andalusians. The pike then did its work, driving back and then breaking the Muslim front ranks. A few men stood their ground, but most shrunk before those awful shafts. They struggled to fall back against the press of those behind them; they flatted themselves on the ground; they dodged; they gripped, frantically trying to redirect incoming pikes. Anything to avoid being impaled.

To the Portuguese cavalry detachments watching from the wings, it was an impressive display of élan, but their pride in their comrades was quickly consumed by the horror of the yawning gap opening before them. The charge of the advance guard had literally torn a side off the square, creating a breach that exposed both the noncombatants and their own rear to attack. But there was no stopping now. Success depended upon a quick, determined, and disrupting blow to the enemy’s center.

Forward the Aventuros pressed, further into the awful din of close combat, deeper into the gut of the colossus. It was like Alexander the Great at Issus. The Muslim center was in clear confusion now. The Andalusians, the bulwark of the Saadian army, were bending. A few moments later, the center gave way, men fleeing into any crevice in the formation—left, right, and rear—leaving two of the sultan’s standards in Christian hands. A momentary lull followed as the renegades, bruised and rattled by the rout of the first line, pulled themselves together for the enemy assault, and the Aventuros slowed as they staggered over mounds of enemy dead. The Portuguese had a clear view of the sultan’s command post. It was almost within arquebus range. For a moment, victory seemed within reach.

Then, at the critical moment, the Christian attack stalled. The reason is not entirely clear—indeed, the details of the battle are blurred from this point on. According to Rebelo de Silva’s later account, Pedro de Lopes, one of the sergeants major of the Aventuros, halted the advance. He was, Silva wrote, overextended, deep in the mass of Moorish infantry and without supporting regiments on his flanks. Fearing that his men might be surrounded, Lopes halted the advance just when they were about to take the Muslim guns. The Castilian and German contingents, keying on the center, too wavered, then stopped. In an instant, the momentum of the attack, and with it the advantage of the pike, was lost. The renegades resolve stiffened, and they came forward to fill the ranks of the remaining Andalusians. The Christian advance guard, greatly outnumbered, its zeal expended, gave ground, and their artillery was overrun. Pedro de Mesquita was shot down trying to save his guns. [36]

Whether Lopes issued the “fatal” order, as one writer put it, is unknown, but like many details it has been accepted as a fact and parroted in many different accounts of the battle.[37] That such an order, if it was given, had any impact on the outcome is doubtful. The Aventuros were probably too hotly engaged to obey such a command, even if they had been able to hear it above the pandemonium of close combat. What stymied the initial attack was almost certainly the lack coordinated action among the regiments of the advance guard and the cavalry. Luis de Oxeda’s eyewitness account of the initial Portuguese charge spoke of disorder, a word that appears frequently in similar accounts of the battle, and a clear indication of the inept leadership and poor training of the Christian forces. Oxeda wrote:

| Already, in this first assault and engagement, there was among our men disorder, because the Portuguese nobles, the Aventuros, wanting courageously to have the advantage over the Castilians in being the first to engage with the enemy, muddled their squadrons; and the Germans, being the heaviest armed and of a less impetuous character, were unable keep up with their companions, resulting in the first and principal corps of our army arriving in disorder, though with much courage, in this first engagement and attack, they put to flight the two corps of the Zouaoua and the Gésules, taking their two banners.[38] |

The Muslims now seized the initiative. From the horns of the crescent, hundreds of horsemen raced into the breach to attack the rear of the Castilian and German formations. All down the rear line of advance guard, pikemen wheeled about like a chorus line to deploy their pikes against the charges. Within minutes the Moors were engaging the Aventuros rear line and the entire formation was surrounded and cut off from the rest of the army.

Seeing the extremity of the advance guard, the Duke of Aviero determined to act. Sebastian had explicitly told his commanders to await his order for any maneuver, but this was an emergency, and there was no time to dispatch a messenger to the other side of the formation. He decided to attack the Moorish left straight away. Marshalling the contingents of Meneses and Moulay Mohammad, the duke led the cavalry charge that drove the Moorish horse facing them off the field. Many reportedly did not stop until they reach Fez, over one hundred kilometers away. Rallying his men, Aviero took them headlong into the exposed left flank of the Saadian main body. The Muslim infantry, having only regrouped from the initial Christian charge, was thrown into confusion once more. The Portuguese pressed up the slope, flanking the Muslim guns and spreading panic among the less disciplined troops. Perceiving defeat, many of the tribal reserves began to take flight. “Believe me,” wrote Joseph Valencia, “we thought to lose all.”[39]

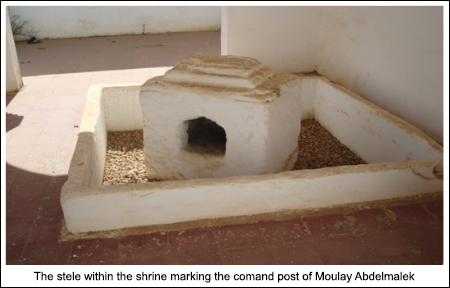

Abdelmalek summoned his last strength to try to stem the tide. Furious at seeing his line buckling and his cavalry being dispersed, he struggled into the saddle and began to exhort his troops to resist. The exertion was too much, and the sultan shortly collapsed into the arms of his bodyguards. They carried him back to his tent. He was still conscious when, according to legend, he looked up at Ridwan and touched a finger to his lips.[40] It was his final command: no one must know of his death until after the battle. Within a half hour, with Ridwan and Valencia at his side, Abdelmalek breathed his last. He was thirty-seven-years-old.

He had held on long enough. The Portuguese army had already spent itself. Their only hope of victory had been in landing a shattering first blow, but their attacks were piecemeal, and there were no reserves to exploit success.

Aviero’s cavalry became scattered, and, before he could regroup them, Moorish cavalry reserves counterattacked. Those Portuguese cavalrymen who were not surrounded and overwhelmed were pursued pell-mell back into their own lines, trampling and sowing chaos amongst the German infantry.

The same scene was played out on the left flank where Sebastian followed Aviero’s example in charging the Moorish cavalry facing him. Once more, the Portuguese’s initial success was lost when they failed to re-form in time to confront a counterattack by Muslim reserves. Once again, they were chased back into their own lines, where this time they trampled the regiment of Italians and Castilians. As Nieto described:

| At the time the Christian soldiers had defeated the Moors’ advance guard, the rest of Sebastian’s army did not pursue victory, having no one who commanded or organized them. And so the soldiers were required to retire to where they began, and the Moors, seeing only that the enemy cavalry had set upon their men, and no one came to their support, sent a multitude of cavalry and soldiers to beat and to kill and to chase them back into [their own] infantry, with no small disorder and confusion among the Christians.[41] |

With this action, the Portuguese cavalry was effectively destroyed. The initiative now passed completely to the Moors.

Sebastian was no general. He was a fighting man, whose storybook concept of command was with sword in hand and leading by example. From the outset of the fighting, the Portuguese army was without direction, as its commander abdicated to the fray. If he did little to ensure the success of the army, as the tide turned Sebastian fought like a lion to save it from annihilation. The king battled with fanatical courage, rushing here and there, bringing reinforcements, and leading cavalry charges in a futile attempt to hold the square together. Bloodied with, it was later said, three horses shot from beneath him, Sebastian was relentless. It was said that he killed as many of the enemy as any man in the army that day.[42]

The Muslim army too fought without much direction. Moulay Ahmad’s role in the fight would later be subject to scrutiny, since he carried away much of the credit for the victory, including the honorific title of al-Mansur (the Victorious). His court scribe, Abdel Aziz al-Fishtali would later take pains to play up his master’s bravery that day, how he took a bullet and had a horse shot from beneath him, yet fought on through the afternoon, charging and countercharging the Christian left, and attacking the rear guard. The fact that his command was nearly routed early in the battle was unmentioned. Perhaps it was al-Mansur who rallied the reserves and led the counterattack that defeated Sebastian’s cavalry force. He may have been a very competent tactical commander, but there is no evidence to support anything more. Al-Mansur certainly did not lead the army to victory, as has often been implied. He might have done so had he learned of his brother’s death during the battle, but this was not the case. Whatever credit may be claimed for the victory belongs to Abdelmalek, who prepared the army for the battle and inspired it to survive long enough for the fight to become a matter of numbers and, ultimately, of brute force.

The Moorish cavalry, now unimpeded, swarmed in from both flanks, encircling the Christian army. They homed in on the gaps in the formation, circling and hacking at the beleaguered regiments, penetrating the line of wagons and attacking the hapless Portuguese conscripts. Some fought for their lives, others fled to hide among the noncombatants. Many threw down their arms and begged for mercy, only to be cleft by the scimitar.

Yet, at this desperate hour, a glimmer of hope suddenly shone. Antonio appeared through the group of Tangiers cavalry that surrounded the king and with effort prodded his terrified mount to Sebastian’s side, crying, “Courage, courage! The sultan is dead!”[43] The word was out, though the faithful Valencia and Ridwan had done their best to conceal the truth. The dead man was hoisted up on cushions as the battle raged all around, a prop in a last subterfuge. Valencia pretended to go on caring for the ailing sultan, and Ridwan issued orders in his master’s name. The chamberlain received officers and messengers before the royal tent, disappearing inside and emerging a moment later with order, “The sultan orders you to attack here,” or to the faint-hearted, “The sultan orders you to hold fast.”[44] One may wonder of the impact of this charade upon the battle, but the act worked well enough and for long enough. No doubt men on both sides saw Abdelmalek fall from his horse and assumed him felled by a bullet. Reports of his demise, however, came too late to influence the outcome.

By noon the contest had been decided. The hours that followed were an agonizing and senseless battle of attrition.

The van of the Portuguese advance guard, its flanks crushed, fought on gallantly but with failing strength. It was the same all across the battlefield, as Christian regiments engaged in their individual fights for survival. Brave men, though they had not made much of a contest of it, they now made the enemy pay dearly. Their ailments and animosities were forgotten, and they battled hard, shoulder to shoulder.

Muslim numbers had already turned the tide; now their matériel superiority made itself cruelly felt. The Saadian mounted arquebusiers employed the caracole, coming forth in waves, closing to point-blank range, discharging their weapons, and then wheeling back to reload. The Aventuros and the Germans hunkered down behind their pikes, but as their fire slackened they started dropping at a steady rate. The Italians and Castilians, running out of ammunition, lunged at their tormentors with daggers, dragging men from their saddles and killing scores, yet still the Muslims came.

Two, three, four hours of steady combat with no chance to disengage. Behind the thinning palisade, the pikeman’s only succor was in scavenging the dead for water and rations. By midafternoon, those still in the fight were dying of the heat and at the end of their strength. The newfangled firearms were gone. It was back to maces, halberds, axes, and swords. They fought on, beyond the limits of endurance and against far worse than defeat.

The Portuguese army, its seams pulled open and hotly engaged from all sides, was in ever-shrinking pieces. Watching the disintegration, Captain Aldaña observed matter-of-factly, “Not one of us will escape today!”[45] Out in the open plain with no cover and insufficient firearms and ammunition to hold the enemy at bay, the Christians were easy targets. The sergeants took over as the officers went down in a steady procession—Martin of Burgundy, Francisco de Tavora, and Alfonso de Aguilar. Death was indiscriminate. The bishops, the papal nuncio, and dozens of priests littered the ground alongside the knights and the common soldiers.

Thomas Stukeley was also dead. In all probability, he was among the first killed that day, being torn apart by a Muslim cannon ball during the brief exchange of artillery. But so controversial a character could not have a simple exit, so there would be another account of his death. According to this version, popularized in the play The Famous History of the Life and Death of Captain Thomas Stukeley, he was murdered by his own men. The Italians, who already despised their leader for bringing them to such grief, suffered an irretrievable blow to their pride at having to fight among the Castilians. Stukeley, lacking confidence in them, had divided them into sections and distributed throughout the Spanish regiment. G. Maffei’s account includes both possibilities:

| There, the moment the battle starts, Stucley [sic] abandons his Italians, who were the first in the engagement, and noiselessly goes over to the Castilian ranks. According to many, he had his legs torn off by an artillery shot. Others affirm, however, that in the midst of the battle he was injured by both enemy shots and by the shots of his own men, who hated him.[46] |

Stukeley was fifty-three-years-old, too old to be lying in pieces, bleeding out into this godforsaken land. Had he any final thoughts as he lay blinking at the sky, it might have been of his own mantra—that every action be “a step toward a crowne.” How then, by all the saints, did he end up here?

Among the Christians it was a common thought that day.

Resistance was ebbing, the outcome inevitable and clear. Panic was generalized now. The main body, a huddled mass of man, beast, and baggage, raked by gunfire from all angles, was paralyzed with fear. The terror built as the square pressed in on itself, man and beast colliding, trampling and being trampled. An eyewitness wrote, “This Army, which did contain three miles in compass, was in an instant consumed by the sword, and did so restrain itself through fear, that a small room might contain it.”[47] Several barrels of gunpowder exploded, adding to the anarchy. Moorish horsemen poured in from behind, the rear guard having dissolved completely. Sebastian’s attempt to bring reinforcements arrived too late to restore the situation.

The battle was turning into a slaughter from which few had the opportunity to flee, though many in their desperation tried. Some lay among the dead in hopes of disguising themselves and escaping in the night. Others left the ranks in hopes of one last embrace from loved ones in the baggage train. From opposite sides of the line, Luis Nieto and Vincent LeBlanc described the death throes:

|

[Our soldiers] being so surrounded from all sides, without powder or ammunition with which to fight, the powder lacking from having been burned during the battle by their own soldiers, if there had been any to fire it would have been used against their own number with the intent of stealing the wagons, and the multitude of cruel fugitives fled the enemy with such haste that they fell over one another, and overwhelmed by the [enemy] cavalry, it was piteous to see many suffocate, to the extent that the troops were in heaps, piled as sheaves of wheat at the harvest, one on top of the other.[48]

There were some [who] mingled themselves among the dead, to save their lives. ‘Twas sad to see 200 sucking children, and above 800 women, boys, and girls, who had followed their father and mother to inhabit this country, who had loaded chains and cords to fetter the Moors, and [now] served for the Christians themselves.[49] |

Moulay Mohammad had no intention of being captured. Never enthralled with Sebastian’s plan, he was quick to lose heart when the tide turned. After the Moorish cavalry overwhelmed Aviero’s and his own, Moulay Mohammad and a handful of followers attempted to save themselves by fleeing back across the Makhazen, presumably over the same ford the Portuguese army had used the day before. However, the tides were high at midday and the former sultan did not know how to swim. Thrown from his mount and likely crushed by it as well, Moulay Mohammad drowned. Among those of his companions who died that day was the historian and author Ibn Askar, who would later be celebrated as a chronicler of Moroccan Sufism.[50]

The end was near. One by one, the knots of men that once were regiments succumbed to the incessant onslaught. The Aventuros, then the Italians, then Castilians were in turn overwhelmed. Somewhere in the melee the king remained, accompanied by a dwindling retinue that included Nuño de Marcarenhas, Vasco de Silveira, Christovão de Tavora, the Count of Vimioso, Luis de Brito, and a few remaining Tangiers cavalry.

The accounts of Sebastian’s last moments are many, often conflicting, and unverifiable. Most agree that the nobles pleaded with their king to save himself, to take flight or to surrender. “What resource is left to us?” bawled Christovão de Tavora. The Count of Vimioso, forgetting, appealed to the king’s humanity. “What other can happen,” he asked, “than we should all die?” To which Sebastian apparently replied with some last bluster, “To die yes, but little by little!”—or words to that effect.[51] And he continued to circle, red-faced and bloodstained, and looking for God only knew what. A few moments later he was gone, separated from the rest of the group. If anyone saw him fall, he did not live to speak of it. Later, it would be reported that the king had been slain by Moorish or Arab soldiers while trying to surrender, but this is one of many embellishments of the battle that has never been proven.[52]

As the afternoon drew to its terrible conclusion, the chaos reached a crescendo. Around the smashed wagons and their scattered paraphernalia, the tangled, smoking heaps of human and animal cadavers, above the cries of the dying, the entreaties of the wounded and the captives, and the wailing of all those terrified souls that was scarcely audible above the din, a new battle was commencing, that of the fight for booty.

The coup de grace came cruelly and from an unexpected quarter. A swarm of Muslim irregulars who had lingered on the periphery of the battle, impatient to join the pillage that was now beginning, intervened to hasten the end. They fell on the exhausted, blood-soaked survivors and, with their crude instruments, clubbed and hacked them down. Among the last to fall were Christovão de Tavora, Vimioso, Aviero, and Aldaña.[53] Meneses and Silva were among the notables taken prisoner, along with the youth, Barcellos, who was pulled from his carriage and tossed into the air repeatedly by jubilant Moors, who had mistaken him for the king.[54] It was five o’clock and the battle was over. For the thousands of noncombatants, the horror was only beginning.

Far to the west, off the coast of solitary Larache, where hours ago had reached the brief echo of cannon fire, Diogo de Sousa and his 800 crews watched and listened still, though they knew that only tomorrow might bring news. They lingered at their stations, uncertain, somewhere between pensive and edgy, as the shadows slowly dissipated and the first stars appeared. A few moments later the sun dipped into the horizon and went down on the last crusade.

News of the debacle, the Battle of the Three Kings, as they were already calling it for the dead sovereigns (the Moroccans referred to it as the Battle of Oued el-Makhazen; others called it the Battle of Ksar el-Kébir), spread across the Mediterranean. Everywhere there was the same reaction—one of incredulity. Many of the courts of Europe asked for confirmation. How was this mighty empire laid low by a Barbary rabble? It was inexplicable.

In the years ahead, Western chroniclers would attribute the Portuguese defeat to many reasons. Few of them involved the competence of the Moors. The composition of the army was called into question, as was the suitability of the tercio, the overreliance on the pike, and the paucity of cavalry. There were too few firearms and inadequate logistics. The tactics were flawed. The dithering at Arzila sacrificed the element of surprise and allowed the enemy to mass. The decision to stray from the coast sacrificed the advantage of naval superiority. Lastly, there was a lack of centralized command and control during the engagement itself. It was all of these things, but foremost it was about an absence of sensible leadership that brought the army to a battlefield without a single advantage over its enemy. And still, if only for a moment, it almost carried the day.

On the other hand, the Portuguese defeat was as much due to the competence of its enemy as its own shortcomings. The Saadian victory may be attributed to the modernization of the army, including the development of a core of professional soldiers; and Abdelmalek’s emphasis on infantry added a key component that allowed the Saadians to fight a set-piece battle in the European style. Furthermore, the equestrian tradition gave the Moors the mobility advantage. And, lastly, and most importantly, it was a matter of leadership. Moulay Abdelmalek’s performance stands in sharp contrast to that of Sebastian. Both met heroic ends, but only one is remembered as a hero.

On the other hand, the Portuguese defeat was as much due to the competence of its enemy as its own shortcomings. The Saadian victory may be attributed to the modernization of the army, including the development of a core of professional soldiers; and Abdelmalek’s emphasis on infantry added a key component that allowed the Saadians to fight a set-piece battle in the European style. Furthermore, the equestrian tradition gave the Moors the mobility advantage. And, lastly, and most importantly, it was a matter of leadership. Moulay Abdelmalek’s performance stands in sharp contrast to that of Sebastian. Both met heroic ends, but only one is remembered as a hero.

The casualty figures were never recorded but most estimates place the Moorish dead at about 5,000 and the Christian at between 8,000-10,000.[55] This does not include the many seriously wounded who would subsequently die of their injuries or associated complications. Fortunately, the economic aspect of Barbary warfare prized captives; had the Moroccans followed Turkish proclivities for dealing with prisoners, the losses would have been truly catastrophic. As it was, hundreds of captives would be subsequently ransomed, including Meneses, Silva, and the Duke of Barcellos. Viewed through the optic of total war, such casualties seem fairly modest, but in the context of earlier times, they were high indeed. For example, 9,000 died at the Battle of Pavia in 1526; more than three centuries later about 7,000 died at the three-day Battle of Gettysburg.[56] These figures provide some indication of just how hard-fought was the Battle of the Three Kings.

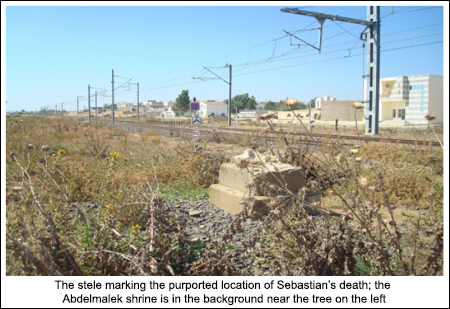

Late in the afternoon of August 5, Sebastian’s remains were identified and covered with quicklime for preservation. As a gesture of good will, on December 6, al-Mansur turned the remains over to the governor of Ceuta. The body was transported with great ceremony to the royal necropolis at the Jerónimos Monastery of Belem, where a final burial took place in the presence of Philip.[57]

The Battle of the Three Kings was a boon to al-Mansur. It provided prestige—baraka (divine favor) —which was key to consolidating a new regime. The windfall of ransom money enabled him to launch a building spree, including the magnificent El Badi Palace in Marrakech. His kingdom became player on the international scene, in Cold War terms, a nonaligned country between Christian Europe and the Ottoman Empire. Al-Mansur parlayed his brother’s military reforms into a trans-Saharan empire. In 1590, he dispatched a small army of primarily Andalusian infantry, many of them veterans of the Battle of the Three Kings, across the Sahara to conquer the Songhay kingdom. In two set-piece battles, the Moroccans blasted apart their more numerous foe, establishing a colonial government in Timbuktu. Moulay Ahmad al-Mansur would rule until 1603, when he died of the plague.

The Battle of the Three Kings punctuated the end of the long struggle for Morocco that began with the Portuguese conquest of Ceuta in 1415. It upheld an independent cultural and political entity in northwestern Africa, deflecting Iberia notions of a neo-reconquest and Turkish designs to bring Morocco into the Ottoman orbit. In this sense, it was central to the development of a Moroccan national identity. In a larger context, the battle is often considered to have brought to a close the Crusades, or Christian holy wars of reconquest, that began in 1096.

While this would seem quite significant, the battle’s importance has not been universally accepted. Henri Terrasse described it as “an accidental episode without precedent and without consequence.”[58] He is not alone in this interpretation. This was not, after all, Mohács or the Blackbird’s Field, where defeat led to the subjugation of the beaten. In this case the victor did not even bother to chase the vanquished from their coastal enclaves. The Portuguese would not quit Morocco until 1769, when they abandoned Mazagan.

No doubt, many historians denigrate the battle since the campaign was chimerical from the start. Had Sebastian succeeded in winning, it would have altered little. Maybe Morocco would have been fractured anew, but it would not have been conquered. In the words of one historian, Morocco would have been an “indigestible lump” in Portugal’s stomach.[59]

Both points are incontestable and ultimately irrelevant.

The battle did matter, enormously. Most dramatically, it helped to bring about the end of the Aviz dynasty and Portugal’s great power status. Sebastian left his country bereft of leadership, an army, treasure, and ultimately the capacity to maintain its independence. King-Cardinal Henry tried to gain papal dispensation to marry, a futile gesture, pathetic enough for a man of his age and for the bride, the thirteen-year-old daughter of the Duchess of Braganza, let alone for the politics involved. All knew that Pope Gregory would not make such an exception to side with the weaker party and against the Catholic king (Philip). When Henry died in 1580, the only serious Portuguese claimant was Antonio, Prior of Crato, but he was no real challenger without an army at his back. Philip had the more persuasive argument, John III’s testament and the Duke of Alba’s sword, and he used both that year to become king of Portugal and the Algarves.

While Philip was careful to respect Portuguese territorial integrity, his enemies did not. The Dutch in particular saw Portugal’s Indian Ocean and Asiatic possessions as prizes to be won in the broadening war for overseas colonies. By the time a Portuguese king once more sat on the throne in Lisbon, the empire had lost many of its overseas possessions to that nation—in the East Indies, Ceylon, and along the Malabar Coast. In this light, the Battle of the Three Kings may be considered as the beginning of the end of the Portuguese Empire.

Spain appeared to be a clear winner in the failed Portuguese adventure of 1578, but such was hardly the case. The Iberian union was doomed to failure, despite Philip’s best efforts to accommodate his newest subjects. The animosities were too great. When Philip died in 1598, the union was already moribund, though it would be another forty-two years before Portugal would rebel and start to reclaim its independence under a new dynasty, the House of Braganza. A long war would be required to do so. One Portuguese possession, Ceuta, chose to stay with Spain. Today, it and the enclave of Melilla remain under that nation’s flag, vestiges of the last crusade and legatees of it burdens.

Show Notes

© 2026 Comer Plummer, III.

Published online: 05/15/2022.

Written by Comer Plummer. If you have questions or comments on this article, please contact Comer Plummer at: comer_plummer@hotmail.com.

About the author:

Comer Plummer is a retired US Army Officer. He served from 1983 to 2004 as both an armor officer and Middle East/Africa Foreign Area Officer. He is currently employed as a DoD civilian and living in Maryland with his wife and son.

* Views expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily represent those of MilitaryHistoryOnline.com.