The Schlieffen Plan and a Two-Front War

By Peter Kauffner

Few plans have become famous in their own right. Alfred von Schlieffen’s plan to invade France through Belgium is an outstanding exception. Schlieffen was head of the German General Staff, the army’s planning division, from 1891 to 1906. A modified version of his plan was used when World War I broke out in August 1914.

So much has been written about the plan over the years it may sound unlikely that there is anything new to say. But a great deal of fresh scholarship was published for the hundred year anniversary in 2014, including translations of the deployment plans.

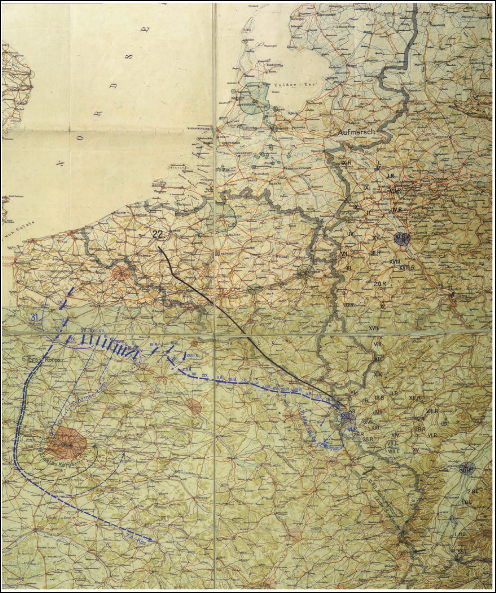

A map from Schlieffen’s final deployment plan of 1905. It was recovered from the German archive.

It is often claimed that the plan was a response to the threat of a two-front war. Yet Schlieffen’s own writing shows that this was not his motivation. The plan is better explained as an example of “cult of the offensive,” an aggressive approach to military planning that was popular in various nations at this time. Historians have long seen Schlieffen as a master technician of war, but political pressures from Kaiser Wilhelm II and others may have played a role in the development of the plan.

In the campaign of 1914, the Germans occupied northeastern France. When they ran out of supplies, they dug in along the Marne river. Four years of trench warfare followed. The war ended in German defeat.

Origin of the plan

The reference works agree that the Schlieffen Plan was a response to the threat of a two-front war. This claim appears in Britannica, Brockhaus Encyclopedia, and many other standard references. (Gross, 1, 68)

But it seems that this was not Schlieffen’s view. “In a war against Germany, France will probably at first restrict herself to defense, particularly as long as she cannot count on effective Russian support,” according to the Memorandum. This would certainly have been true in 1905 when Russia had its hands full with Japan and revolution. At very least, it was an unlikely time for a Russian attack.

If Schlieffen wasn’t worried about foreign invasion, what problem was he addressing? Historian Robert Foley presents an alternative theory concerning the plan’s origin. Schlieffen’s favored strategy was the counteroffensive, that is, to strike when the enemy was fully extended. The switch to an offensive strategy was motivated by the fear that the French would not mount an offensive of their own, according to Foley. This could result in repeated German frontal attacks on French positions, an outcome Schlieffen feared. (Foley, Origin)

Schlieffen’s shift from the counteroffensive to flanking and envelopment can be seen as early as 1899 in the deployment plan he produced for that year, according to Foley. (Foley, Origin)

Schlieffen laid out his plan in a “Great Memorandum” dated December 1905. (Schlieffen, 163) In some ways, it was a continuation of earlier plans. “Schlieffen’s ideas about this offensive developed from relatively shallow outflanking maneuver toward the final grand envelopment of the 1905 memorandum,” according to Foley. (Foley, War, 70)

The 1905 plan assumes resources and soldiers that Germany did not have. The plan can be thought of as an ideal for the future. The memo was used to create a deployment plan that Schlieffen passed along to his successor Helmut von Moltke. It was, “A program for further expansion of the army and its mobilization,” as the Reich Archive described it in its 1925 catalogue. (Gross, 103)

While Foley and Gross tracked the plan’s development using the German archive, Jan Karl Tanenbaum used the French archive. Starting in 1900, German military academies began to emphasize offensives, flanking, envelopment, and avoiding frontal attacks, according to the French attaché in Berlin. The following year, military maneuvers began to stress envelopment. The Belgian high command warned the French that these changes suggested that a plan to invade France through Belgium was being developed. Although work on the German rail system suggested that it was being upgraded for military use, French intelligence concluded that it would be years before the Germans had enough rail capacity to carry out a broad-front advance. (Tanenbaum, 151-152)

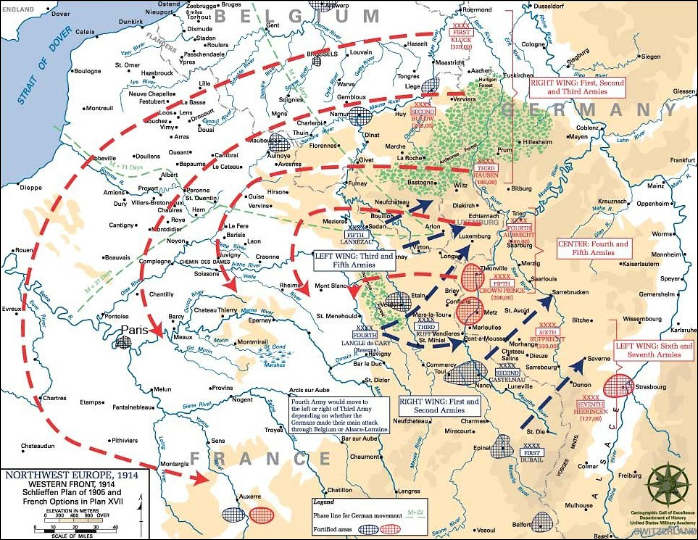

This is the classic view of the Schlieffen Plan. “Let the last man on the right brush the Channel with his sleeve,” Schlieffen once said. This version features a broad front that disregards practical limitations. The map was created in 1938 by the United States Military Academy for a course entitled ”History of the Military Art.”

Cult of the offensive

Gerhard Ritter and most historians since have portrayed Schlieffen as a “pure military technician,” uninterested in politics. In contrast, Gerhard Gross emphasizes Schlieffen’s political role and his relationship with Wilhelm, but confesses that he hasn’t solved the riddle. (Gross, 111-112)

One factor that got Schlieffen promoted to chief of staff was that he allowed the kaiser to command and invariably win in maneuvers. Neither his predecessor nor his successor indulged the kaiser's boyish enthusiasms in this way. (Röhl, 199, 300)

The Schlieffen Plan is the epitome of a style of military thinking called the cult of the offensive (L’offensive à outrance). According to this doctrine, if you can take the offensive, you should. (Van Evera)

This doctrine can be traced to the writing of Prussian strategist Carl von Clausewitz, whose work On War was published in 1832. It became influential in 1890s when it was promoted by Ferdinard Foch at the French military school, L'École de Guerre. When Joseph Joffre became commander in chief in 1911, it was adopted as policy. Schlieffen endorsed it in a 1909 essay: “A strategy of exhaustion is impossible when the maintenance of millions necessitates the expenditure of milliards.” (Schlieffen, 200) This a reference to a defensive strategy used by Frederick the Great in the Seven Years War.

A colorized image of German military planner Alfred von Schlieffen.

Where is Russia?

One remarkable feature of the 1905 Memorandum was that it focused exclusively on France and ignored Russia.

Wilhelm was attempting to improve relations with Russia in 1904-1905, so he may have asked Schlieffen not to distribute plans for an attack on Russia to avoid damaging relations. (Gross, 112). The intelligence war may also explain Schlieffen’s tendency to exaggerate the resources at his command, including the use of “ghost divisions.” (Gross, 107)

The kaiser’s concern that plans could leak was well-founded. In late 1903, an agent called The Avenger sold a copy of the deployment plan to French intelligence. During negotiations, The Avenger kept his face covered with a bandage, but allowed his preposterous Prussian mustache to stick out in a manner worthy of a spy thriller. It was an extraordinary breakdown of security at the General Staff, an organization that otherwise never leaked. Did an officer betray Germany, or did Schlieffen plant documents to assist the kaiser’s diplomatic efforts? (Tanenbaum, 153-154)

Crises in Russia and Morocco

When Russia moved its troops east to fight Japan in January 1904, Wilhelm was overjoyed. He wanted to redeploy the troops that had been protecting the east from Russian invasion to strike west at France. (Röhl, 309) War Minister Ernst von Einem explained that the German army was not yet ready for war. German artillery was inferior to French artillery. An upgrade to recoilless artillery was expected to take a year. The infantry was in the process of being equipped with new rifles and new ammunition. A high seas fleet had yet to be built. The biggest problem of all was that the German public did not support a war for Morocco and that the socialists could revolt, as had just happened in Russia. (Röhl, 327)

The Schlieffen plan lay dormant for the next few years while the German government channeled resources into building a high seas fleet. The Agadir incident in 1911 convinced the Germans that the Anglo-French alliance was solid. Germany could not outbuild a combined fleet, so the naval strategy was abandoned and resources were shifted to the army.

Years of propaganda by the Naval League and the Pan-German League had an impact. The German public was far more belligerent in 1911 than it had been in 1905. The Reichstag approved expansions of the army in December 1911, October 1912, and, most notably, in July 1913. Germany was spending itself broke, but Schlieffen’s plan was at last ready to go.

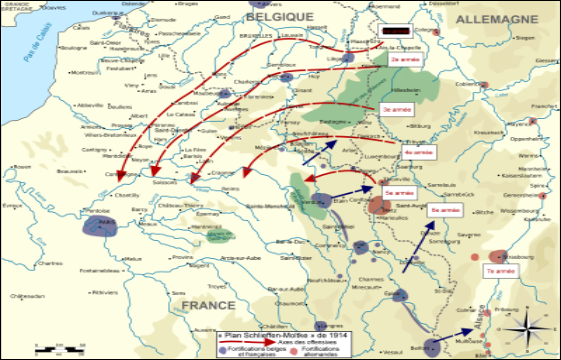

Deployments in August 1914. This is the Schlieffen Plan as modified by Moltke, German commander at the start of World War I. Notice that Moltke, unlike Schlieffen, did not deploy an army west of Paris. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plan_Moltke-Schlieffen_1914.svg

Why did the Schlieffen Plan fail?

The view that the plan was a military masterpiece was promoted in the 1920s by a group of writers called the Schlieffen School. The group worked with the Reich Archive to rehabilitate the image of the German military. Their views went largely unchallenged until 1958, when Gerhard Ritter’s The Schlieffen Plan: Critique of a Myth was published.

Ritter answered the question that now plagues British schoolchildren when they take their O-level exam: “Why did the Schlieffen Plan fail?” Unfortunately, the results don’t testify well to the state of British education. The student answers that I have seen emphasize that the Belgians held up the Germans for ten days at Liége or that the British held them up at Mons. These actions supposedly prevented the plan from being completed in the six weeks allotted.

Schlieffen proposed an all-out offensive against an army whose firepower was roughly equal to his. A successful offensive requires that the attacker have a significant advantage in terms of firepower or something else. The only advantage that Germany had was that the French military’s single-minded focus on Lorraine. As this sector was well fortified, the attack here did not greatly concern the Germans. The French had interior lines of communication and a rail system to redeploy for counterattacks. The Germans, meanwhile, marched on foot as the French had destroyed the rail system when they retreated.

The plan contemplated a flanking action that would wheel around Paris from the west. This required far more soldiers than Germany had, either in Schlieffen’s time or in 1914. In the end, Moltke deployed all his troops to advance east of Paris and hoped for the best. The Schlieffen School faulted him for modifying the plan in this way, but it's hard to see what else he could have done. More troops would not have helped. Supply issues pushed the rail system to the limit as it was.

In addition, the plan expected German soldiers to do a superhuman amount of marching. Meanwhile, the French army was expected to retreat without counterattacking or otherwise disrupting the plan. In an era when Ford was producing Model T’s on an assembly line, the problem suggested a need for motorized infantry. But it seems that the General Staff did not have the imagination to think in these terms. (O’Neil, 118)

“The basis for Schlieffen’s formula for quick victory amount to little more than a gambler’s belief in the virtuosity of sheer audacity,” as military historian B.H. Little Hart wrote in the preface to Ritter’s book.

When Moltke’s variant of the Schlieffen Plan was used in 1914, it allowed the Germans to occupy northeastern France. By the time they made it the Marne, they were exhausted and had outrun their supplies, so they dug in. The French did the same.

Although many writers assume that the plan was a tightly-guarded secret, Schlieffen had written about it for Deutche Revue in 1909 (Schlieffen, 194-205). So there was no shortage of opinions. In the aftermath of the battle of the Marne, numerous officers turned on Moltke. “Schlieffen’s notes have come to an end, and so have the wits of Moltke,” wrote future Commander in Chief Erich von Falkenhayn. (Gross, 8) Karl Ritter von Wenninger, the Bavarian military representative, wrote in his diary, “Moltke and his subordinates were completely sterile. They could only turn the handle and run Schlieffen’s film and were clueless and beside themselves when the ball got stuck.” (Mombauer, 59)

French response

To the extent that the Schlieffen plan was successful, it was because the French failed to take advantage of their interior lines to launch counterattacks. Instead, French commander Joffre focused on an offensive to recover the “lost province” of Lorraine. This was in service of a long-standing dream of the nationalists called revanche.

For French intelligence, German army expansion confirmed the correctness of Joffre’s focus on Lorraine. Surely the additional forces would be used to attempt a breakthrough in this sector. (Tanenbaum, 168) The route through Belgium was thus an unprotected flank when war broke out in August 1914.

Alternatives

Did Germany have a better option? On August 1, 1914, the day mobilization was ordered, the kaiser received a message stating that Britain would remain neutral if Germany did not attack France. Overjoyed, he told Moltke: “Now we can go to war against Russia only. We simply march the whole of our army to the east!” (Tuchman, 93) The kaiser saw Napoleon as a role model. He wanted to conquer Europe while avoiding what he saw as Napoleon’s mistake, namely war with Britain. (Röhl, 382)

Moltke responded that this idea was impractical. There was only one mobilization plan and it was to send the German army west. Railway timetables could not be improvised, he said. But Moltke was not telling the kaiser the whole truth. In fact, the General Staff had long maintained a fully developed plan to deploy eastward. Moreover, General Herman von Staab, head of the rail department, conducted annual exercises to make sure that his staff had experience improvising schedules. When he learned of Moltke’s remarks after the war, he published a book to show how the proposed changes could have been made. (Tuchman, 93)

Schlieffen was never committed to the offense against France, but maintained an alternative plan called Aufmarsch II to play defence in the west while mounting an offensive against Russia. This strategy is suggested by the extensive system of German fortification system in Lorraine and Alsace, which had been built up over many years. The multiple rings of forts around Metz were designed as a death trap for the French. But the German offensive through Belgium made this investment so much wasted effort.

The Plans

The Army Archive in Potsdam was destroyed by a British air raid in April 1945. It was long thought that Schlieffen’s deployment plans were destroyed at this time. Ritter recovered Schlieffen’s papers, including his personal copy of the Great Memorandum, from the U.S. National Archive in Washington in the 1950s. In 1996-2000, the records of the East German army archive in Potsdam were transferred to the German Military Archive in Freiburg. In 2002, they were made available to historians at the War History Research Center of the Army as record group RH61. This sparked a period of renewed debate among historians regarding pre-war military planning. A full set of deployment plans for 1893 to 1914 was eventually translated and published in 2014. (Gross, 88, 89, 339-526)

An infantry corps normally consisted of two divisions.

1903-1905

This is the version of the plan that was current at the time of The Avenger incident.

• Aufmarsch I: “State of War with France”

“Crossing the Belgium border is authorized only after explicit order issued by OHL…The entire force with the exception of the Seventh Army will pivot to the left through Belgium. The left wing (Eighth Army) will push to Metz and cover the left flank of the force against Verdun from a reinforced position, if necessary.”

Against France: 25 army corps, 7 cavalry divisions, 11 reserve divisions

Against Russia: 3 army corps, 4 cavalry divisions, 4 reserve divisions.

• Aufmarsch II: “State of War with Russia and France”

“...The preparations for Aufmarsch II are written down only in the form of a study, since this Aufmarsch was considered the less probable case.” As for operations on the eastern front, they “are not probably initially.” (Gross, 401-415)

1904-1905

This was the last set of plans whose production was supervised by Schlieffen. Unlike the previous year, there were two fully developed mobilization plans for 1904-1905. Notice that the number of reserve divisions has increased from 15 to 19.

• Aufmarsch I “State of War with France only,” This is Schlieffen’s original plan to open the war with an all-out offensive against France in the west. Unlike the plan for 1903-1904, it calls for German forces to cross the Meuse River on the way to Brussels, the Belgian capital. It ignores Russia.

“Do not enter Dutch or Belgian territory until OHL gives order to do so…In the event of an advance into Holland and Belgium, the next task of the cavalry divisions…will be to seize the Meuse bridge in Venlo, Roermond, Maaseyck and the railroads, including rolling stock. Direction of the advance will be Brussels,” according to the plan.

Against France: 26 army corps, 9 cavalry divisions, 15 reserve divisions were deployed.

Against Russia: 2 cavalry divisions, and 4 reserve divisions were deployed.

• Aufmarsch II “State of War with Russia and France”

Against France: 23 army corps, 9 cavalry divisions, 15 reserve divisions are deployed.

Against Russia: 3 army corps, 2 cavalry division, 4 reserve division were deployed. (Gross, 409-415)

1905-1911

The deployment plans for 1905-1910 followed the pattern of the 1904-1905 plans. There were generally two options, Aufmarsch I for an offensive against France and Aufmarsch II for an offensive against Russia. For the 1909-1910 plan, an Aufmarsch Ia option was added that splits the difference between plans I and II. The main German force would be deployed against France and a smaller force against Russia. The plans for 1910-1911 and 1911-1912 gave the Aufmarsch I and II options. (Gross, 416-496)

1914-1915

This mobilization plan was used in World War I. It has only one option. “Germany’s preparations for war are first and foremost directed against France,” according to the preliminary remarks. “Russia will probably join France in a war against Germany. The English are expected to the hostile.”

“By 1800 hours on the 2nd mobilization day the Belgian government must decide whether Belgium will be Germany’s friend of enemy,” according to the plan. That will require the Belgians to open immediately the fortifications of L. Huy and Namur to the German army; to make the railroads…available to us; and not to mobilize the Belgian army.”

German strength is given as 26 army corps, 13 reserve corps, 11 cavalry divisions, and 1 Landwehr corps.

Against France: Germany would deploy 23 army corps, 11 reserve divisions, 17 1⁄2 combined Landwehr brigades, and 10 cavalry divisions. three brigades.

Against Russia: 3 corps, 1 reserve corps, 1 cavalry division, and a Landwehr corps of three brigades. (Gross, 517-525)

| * * * |

Show Notes

| * * * |

© 2026 Peter Kauffner

Written by Peter Kauffner.

About the author:

Peter Kauffner lives in Sequim, Washington. He is a writer and a teacher.

* Views expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily represent those of MilitaryHistoryOnline.com.