A Forgotten Chapter: In 1850 a Kentucky Regiment Invaded Cuba

By Dave McCormick

By Dave McCormick

As the Kentucky Regiment entered Quintayros Plaza a Spanish sentinel called out three challenges, hearing no response from the oncoming Kentucky militiamen, he fired his weapon. This alerted the 15 soldiers defending the jail to respond with a deadly barrage, that wounded a few of the Kentuckians, including their commanding officer, Colonel Theodore O’Hara, who suffered a wound to his thigh. The Kentucky Regiment known as the Kentucky Filibusters, was a diverse mix incorporating members from all social strata: unemployed laborers, tradesmen, store clerks, lawyers, and physicians. This was a group of hale and hearty Americans, not a ragtag bunch. Of other fighting units, American and Cuban, the Kentuckians were the first to land on the shores of Cuba and performed as the van of the operation. They were the first to shed blood in in battle; their casualty rate represented one-third of the total casualty count. And these Kentuckians came close to altering the future of Cuba.

British Strategy in the First Anglo-Afghan Wars, 1838–1842

By Robert F. Williams

By Robert F. Williams

Throughout the nineteenth century, Great Britain, the world’s preeminent naval empire, and Russia, one of the preeminent land empires, vied for control throughout Central Asia in the “Great Game.” Twice in forty years, Britain invaded Afghanistan to expand its security bubble in South Asia and prevent Russia from threatening the “crown jewel” of the British Empire—India. However, the British failure to align ways and means with a sensible political end was a critical component of this “Great Game” between the two imperial powers and led to unnecessary bloodshed. The initial invasion in 1838 was prompted by faulty assumptions about the geostrategic situation and the Anglo-Indians’ ability to pacify a politically fractured country by appointing an unpopular former leader as its head. British strategy for occupation focused on creating a strong central government in a country where power was, traditionally, local. Britain had the means to invade the country yet failed to apply its material strength to realistic political ends. Ultimately, though the British suffered a humiliating military defeat in Afghanistan, they maintained an amicable relationship with Afghan leaders following their withdrawal. While the initial strategic ends were not met, shifting assumptions based on a better understanding of the situation allowed Britain to achieve a broader strategic goal of a friendly Afghanistan to provide defense in depth against Russian and Persian influence in its most-prized colony.

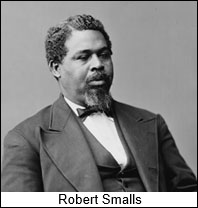

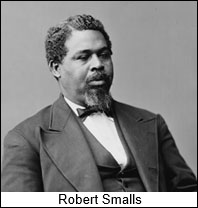

Robert Smalls: From Renegade Slave to U.S. Congressman

By Walt Giersbach

Remarkably few people today know of the illiterate South Carolina slave who stole a warship, ran the Confederate lines to freedom and, within 10 years, had become elected to the U.S. Congress. Robert Smalls’ master knew his teenaged servant was talented, enough so that he hired the boy out in Charleston, S.C., as a longshoreman, then as rigger, sail maker, and finally wheeelman — actually a pilot in all but name only. Smalls was born in the home of his mother’s master, John H. McKee, in Beaufort, South Carolina, in1839. (Either McKee or McKee’s son may have been Smalls’ father, but this is unconfirmed.) When Smalls was a teenager, his mother asked McKee to allow her son to be rented out for work in Charleston, where he was eventually hired as a deckhand on the coastal cotton transport steamship Planter. In short order, Smalls became the ship’s de facto pilot.”

The Battle of Omdurman

By Larry Parker

As darkness fell General Hector Macdonald sat brooding in his tent. It had been a close run thing for him and his Sudanese brigade two days prior. The initial charge broken, General Kitchener foolishly surmised he could take Omdurman by coup de main. Accordingly he ordered his forces out of the laager to pursue the fleeing enemy. The Dervish, although terribly bloodied, were not beaten however. Some 25,000 Mahdists previously hidden behind the surrounding hills took the pursuing formations, now exposed on open ground, in the flank. Fortuitously for General Kitchener his Brigadiers were capable men and his troops well trained, steady and of good morale. As the last unit in the line of march General Macdonald and his men had been temporarily isolated and withstood the brunt of this second great charge. Timely reinforcements, a rain of death from the supporting gun boats and disciplined fire prevailed. Now as his men recovered and the field of battle was cleared there were the inevitable reports to be made. This report was especially delicate. Firstly, to shelter behind the zariba had been foolhardy.

The French vs. German Strategy of Warfare 1871 By Robert Shawlinski and Vernon Yates

Throughout the centuries, the European continent has hosted many wars of conflict, laying waste to its countryside, and killing thousands of its citizens. These outbreaks of violence came about over religion, power, and petty disagreements in wars lasting over one-hundred years in some cases. Even though the human suffering was horrific during these battles, warfare was conducted in an almost elementary approach with strategy as an afterthought. This approach begins to change with the founding and successful expansion of the Prussian Empire across central Europe. The Prussians brought new methods and techniques to the art of warfare through its professional application of strategy as a science and an art. The Prussian Empire during the 1871 war with the French was controlled by the then Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck even the Emperor of Prussia referred to Bismarck due to the power arrangements of the empire. Bismarck had the goal of uniting all Germans under one flag and destroying the threat the French posed from the West.

Romolo Gessi Pasha: Early Counter-Insurgency Lessons from an Italian Soldier of Fortune’s Campaign in Central Africa By Dr. Andrew McGregor

Successful counterinsurgencies typically combine the deployment of superior weapons, competent logistics, advanced tactics and the ability to win the “hearts and minds” of the non-insurgent population. What is striking about the success of Italian soldier-of-fortune Romolo Gessi Pasha (1831-1881) against insurgent Arab traders and slavers in the south Sudan was his ability to overcome a much larger group of fighters who possessed similar weapons, had greater experience in both irregular and conventional warfare, held fortified positions, were at home in the terrain and had wide public support in the most influential parts of Sudanese society, including the military.

Alfred Thayer Mahan: Advocate for Seapower By Larry Parker

In 1865 the United States Navy mustered 700 ships (many of them iron clad and steam powered), mounting 5,000 cannon (many of those rifled, shell guns of the latest design), crewed by 6,700 officers and 51,000 men. In just five years 92.6 per cent of the fleet had been sold, scrapped or laid up. Only 52 ships mounting 500 guns remained in active commission. These, with a few notable exceptions, were crewed largely by the dregs of the waterfront for, as promotion and advancement opportunities stagnated, officers and enlisted personnel left the service in droves taking with them hard won battle experience and years of training. In this environment the eighteen knot USS Wampanoag[1] , first warship to employ super heated steam, was scrapped as congress mandated a return to sail in order to save money on coal.

Americans in the Boer War By Michael Headley

Why did many American men travel thousands of miles to participate in the Boer War (1899-1902) between the Dutch republics and Great Britain in South Africa? [1] There are varied reasons why some American citizens chose to act on their own to become involved in this lesser known war, despite the United States Government’s decision to stay out of this conflict. An examination of the motivations of Americans who joined in the fighting shows that Americans chose to participate on both sides of the Boer War. Those include Americans who harbored hatred for British imperialism such as John Blake and the Irish-Americans; adventurous and liberty-loving citizens represented by John Hassell and the American Scouts; those with entrepreneurial interests within the Transvaal and Orange Free State, inadvertently drawn into the conflict as displayed by George Labram; those who fostered humanitarian and moral issues violated by the British against the Boers; and those who supported the British Monarchy such as Major Frederick Russell Burnham.

Marching to Timbuktu: The Unwanted Conquest of Mali that Made a Marshal of France By Dr. Andrew McGregor

When French troops launched a military intervention against Islamist militants in Mali in January 2013, many of those advancing on the legendary city of Timbuktu may have been unaware that it had been 119 years since a French colonial army column under Major Joseph Joffre had entered that ancient trading capital. Rather than a triumph for France, the 1894 occupation was in fact a planned act of insubordination by Joffre and other French colonial officers. The truth was France didn’t want Timbuktu. Joffre is best known as the commander of all French armies in World War 1 after his victory at the Marne in 1914 was credited with saving France. At the height of his fame in 1915 his military report of the 1894 occupation of Timbuktu was reprinted under the title

Madness in the Mountains: The Charge of the Polish Light Horse at the Battle of Somosierra By Alexander Zakrzewski

On the foggy morning of November 30, 1808, Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of the French, watched impatiently as his Grande Armée lumbered up the rocky slopes of the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains of central Spain. It was the last obstacle before Madrid and certain victory over the rebellious Spanish. In anticipation of his advance, a small but determined Spanish force had fortified the narrow pass that lead through the sleepy mountain village of Somosierra. As the French advance stalled in the face of withering cannon and musket fire, Bonaparte turned to 3rd Squadron of the Chevau-Légers Polonais of the Imperial Guard and impetuously ordered them to charge the enemy positions. Miles from their eastern homeland, the Polish horsemen dutifully responded. The result was an unlikely victory and one of the most spectacular cavalry charges of the Napoleonic Wars.

Fenian Raids - The War That Never Happened By Walt Giersbach

June 6, 1866, turned out to be warm as some 2,000 (or more, or fewer; no one is sure) veterans of the Civil War charged across the United States border at St. Albans, Vermont, and began their attack on British North America. Fenian Brigadier Samuel P. Spear led the attack that would—if successful—hold Canada hostage until the English let go their yoke on Ireland. A preposterous invasion? Not to the thousands of Irish veterans of both the Union and Confederate Armies that had banded together under a different flag. Not to President Andrew Johnson, who was demanding reparations from the British for supporting the Confederate States in the Civil War and would now use the Fenians as a political lever. And certainly not to the British, who were waiting with an exponentially larger force. [1]

Hollow Empire: The French Intervention in Mexico (1862-67) By Timothy Neeno

Beginning in 1862, while the United States was paralyzed by Civil War, the French under Napoleon III tried to create an empire in Mexico under a puppet ruler, the Archduke Maximilian of Austria. Over the next five years of war some 300,000 Mexicans died, and French ambitions were dealt a bruising blow. How had this conflict come about, and how did a weakened, divided nation defeat one of the most powerful empires in the world? From 1521, when an army of conquistadors under Hernán Cortéz marched into the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, until 1821, Mexico was under the harsh rule of Spain. For three hundred years the Spaniards kept tight control of Mexico, limiting her trade to Spain alone and preventing any attempts at self government. After years of unrest and rebellion, the Spanish left Mexico, leaving a land in turmoil.

By Dave McCormick

By Dave McCormick

As the Kentucky Regiment entered Quintayros Plaza a Spanish sentinel called out three challenges, hearing no response from the oncoming Kentucky militiamen, he fired his weapon. This alerted the 15 soldiers defending the jail to respond with a deadly barrage, that wounded a few of the Kentuckians, including their commanding officer, Colonel Theodore O’Hara, who suffered a wound to his thigh. The Kentucky Regiment known as the Kentucky Filibusters, was a diverse mix incorporating members from all social strata: unemployed laborers, tradesmen, store clerks, lawyers, and physicians. This was a group of hale and hearty Americans, not a ragtag bunch. Of other fighting units, American and Cuban, the Kentuckians were the first to land on the shores of Cuba and performed as the van of the operation. They were the first to shed blood in in battle; their casualty rate represented one-third of the total casualty count. And these Kentuckians came close to altering the future of Cuba.

British Strategy in the First Anglo-Afghan Wars, 1838–1842

By Robert F. Williams

By Robert F. Williams

Throughout the nineteenth century, Great Britain, the world’s preeminent naval empire, and Russia, one of the preeminent land empires, vied for control throughout Central Asia in the “Great Game.” Twice in forty years, Britain invaded Afghanistan to expand its security bubble in South Asia and prevent Russia from threatening the “crown jewel” of the British Empire—India. However, the British failure to align ways and means with a sensible political end was a critical component of this “Great Game” between the two imperial powers and led to unnecessary bloodshed. The initial invasion in 1838 was prompted by faulty assumptions about the geostrategic situation and the Anglo-Indians’ ability to pacify a politically fractured country by appointing an unpopular former leader as its head. British strategy for occupation focused on creating a strong central government in a country where power was, traditionally, local. Britain had the means to invade the country yet failed to apply its material strength to realistic political ends. Ultimately, though the British suffered a humiliating military defeat in Afghanistan, they maintained an amicable relationship with Afghan leaders following their withdrawal. While the initial strategic ends were not met, shifting assumptions based on a better understanding of the situation allowed Britain to achieve a broader strategic goal of a friendly Afghanistan to provide defense in depth against Russian and Persian influence in its most-prized colony.

Robert Smalls: From Renegade Slave to U.S. Congressman

By Walt Giersbach

Remarkably few people today know of the illiterate South Carolina slave who stole a warship, ran the Confederate lines to freedom and, within 10 years, had become elected to the U.S. Congress. Robert Smalls’ master knew his teenaged servant was talented, enough so that he hired the boy out in Charleston, S.C., as a longshoreman, then as rigger, sail maker, and finally wheeelman — actually a pilot in all but name only. Smalls was born in the home of his mother’s master, John H. McKee, in Beaufort, South Carolina, in1839. (Either McKee or McKee’s son may have been Smalls’ father, but this is unconfirmed.) When Smalls was a teenager, his mother asked McKee to allow her son to be rented out for work in Charleston, where he was eventually hired as a deckhand on the coastal cotton transport steamship Planter. In short order, Smalls became the ship’s de facto pilot.”

The Battle of Omdurman

By Larry Parker

As darkness fell General Hector Macdonald sat brooding in his tent. It had been a close run thing for him and his Sudanese brigade two days prior. The initial charge broken, General Kitchener foolishly surmised he could take Omdurman by coup de main. Accordingly he ordered his forces out of the laager to pursue the fleeing enemy. The Dervish, although terribly bloodied, were not beaten however. Some 25,000 Mahdists previously hidden behind the surrounding hills took the pursuing formations, now exposed on open ground, in the flank. Fortuitously for General Kitchener his Brigadiers were capable men and his troops well trained, steady and of good morale. As the last unit in the line of march General Macdonald and his men had been temporarily isolated and withstood the brunt of this second great charge. Timely reinforcements, a rain of death from the supporting gun boats and disciplined fire prevailed. Now as his men recovered and the field of battle was cleared there were the inevitable reports to be made. This report was especially delicate. Firstly, to shelter behind the zariba had been foolhardy.

The French vs. German Strategy of Warfare 1871 By Robert Shawlinski and Vernon Yates

Throughout the centuries, the European continent has hosted many wars of conflict, laying waste to its countryside, and killing thousands of its citizens. These outbreaks of violence came about over religion, power, and petty disagreements in wars lasting over one-hundred years in some cases. Even though the human suffering was horrific during these battles, warfare was conducted in an almost elementary approach with strategy as an afterthought. This approach begins to change with the founding and successful expansion of the Prussian Empire across central Europe. The Prussians brought new methods and techniques to the art of warfare through its professional application of strategy as a science and an art. The Prussian Empire during the 1871 war with the French was controlled by the then Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck even the Emperor of Prussia referred to Bismarck due to the power arrangements of the empire. Bismarck had the goal of uniting all Germans under one flag and destroying the threat the French posed from the West.

Romolo Gessi Pasha: Early Counter-Insurgency Lessons from an Italian Soldier of Fortune’s Campaign in Central Africa By Dr. Andrew McGregor

Successful counterinsurgencies typically combine the deployment of superior weapons, competent logistics, advanced tactics and the ability to win the “hearts and minds” of the non-insurgent population. What is striking about the success of Italian soldier-of-fortune Romolo Gessi Pasha (1831-1881) against insurgent Arab traders and slavers in the south Sudan was his ability to overcome a much larger group of fighters who possessed similar weapons, had greater experience in both irregular and conventional warfare, held fortified positions, were at home in the terrain and had wide public support in the most influential parts of Sudanese society, including the military.

Alfred Thayer Mahan: Advocate for Seapower By Larry Parker

In 1865 the United States Navy mustered 700 ships (many of them iron clad and steam powered), mounting 5,000 cannon (many of those rifled, shell guns of the latest design), crewed by 6,700 officers and 51,000 men. In just five years 92.6 per cent of the fleet had been sold, scrapped or laid up. Only 52 ships mounting 500 guns remained in active commission. These, with a few notable exceptions, were crewed largely by the dregs of the waterfront for, as promotion and advancement opportunities stagnated, officers and enlisted personnel left the service in droves taking with them hard won battle experience and years of training. In this environment the eighteen knot USS Wampanoag[1] , first warship to employ super heated steam, was scrapped as congress mandated a return to sail in order to save money on coal.

Americans in the Boer War By Michael Headley

Why did many American men travel thousands of miles to participate in the Boer War (1899-1902) between the Dutch republics and Great Britain in South Africa? [1] There are varied reasons why some American citizens chose to act on their own to become involved in this lesser known war, despite the United States Government’s decision to stay out of this conflict. An examination of the motivations of Americans who joined in the fighting shows that Americans chose to participate on both sides of the Boer War. Those include Americans who harbored hatred for British imperialism such as John Blake and the Irish-Americans; adventurous and liberty-loving citizens represented by John Hassell and the American Scouts; those with entrepreneurial interests within the Transvaal and Orange Free State, inadvertently drawn into the conflict as displayed by George Labram; those who fostered humanitarian and moral issues violated by the British against the Boers; and those who supported the British Monarchy such as Major Frederick Russell Burnham.

Marching to Timbuktu: The Unwanted Conquest of Mali that Made a Marshal of France By Dr. Andrew McGregor

When French troops launched a military intervention against Islamist militants in Mali in January 2013, many of those advancing on the legendary city of Timbuktu may have been unaware that it had been 119 years since a French colonial army column under Major Joseph Joffre had entered that ancient trading capital. Rather than a triumph for France, the 1894 occupation was in fact a planned act of insubordination by Joffre and other French colonial officers. The truth was France didn’t want Timbuktu. Joffre is best known as the commander of all French armies in World War 1 after his victory at the Marne in 1914 was credited with saving France. At the height of his fame in 1915 his military report of the 1894 occupation of Timbuktu was reprinted under the title

Madness in the Mountains: The Charge of the Polish Light Horse at the Battle of Somosierra By Alexander Zakrzewski

On the foggy morning of November 30, 1808, Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of the French, watched impatiently as his Grande Armée lumbered up the rocky slopes of the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains of central Spain. It was the last obstacle before Madrid and certain victory over the rebellious Spanish. In anticipation of his advance, a small but determined Spanish force had fortified the narrow pass that lead through the sleepy mountain village of Somosierra. As the French advance stalled in the face of withering cannon and musket fire, Bonaparte turned to 3rd Squadron of the Chevau-Légers Polonais of the Imperial Guard and impetuously ordered them to charge the enemy positions. Miles from their eastern homeland, the Polish horsemen dutifully responded. The result was an unlikely victory and one of the most spectacular cavalry charges of the Napoleonic Wars.

Fenian Raids - The War That Never Happened By Walt Giersbach

June 6, 1866, turned out to be warm as some 2,000 (or more, or fewer; no one is sure) veterans of the Civil War charged across the United States border at St. Albans, Vermont, and began their attack on British North America. Fenian Brigadier Samuel P. Spear led the attack that would—if successful—hold Canada hostage until the English let go their yoke on Ireland. A preposterous invasion? Not to the thousands of Irish veterans of both the Union and Confederate Armies that had banded together under a different flag. Not to President Andrew Johnson, who was demanding reparations from the British for supporting the Confederate States in the Civil War and would now use the Fenians as a political lever. And certainly not to the British, who were waiting with an exponentially larger force. [1]

Hollow Empire: The French Intervention in Mexico (1862-67) By Timothy Neeno

Beginning in 1862, while the United States was paralyzed by Civil War, the French under Napoleon III tried to create an empire in Mexico under a puppet ruler, the Archduke Maximilian of Austria. Over the next five years of war some 300,000 Mexicans died, and French ambitions were dealt a bruising blow. How had this conflict come about, and how did a weakened, divided nation defeat one of the most powerful empires in the world? From 1521, when an army of conquistadors under Hernán Cortéz marched into the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, until 1821, Mexico was under the harsh rule of Spain. For three hundred years the Spaniards kept tight control of Mexico, limiting her trade to Spain alone and preventing any attempts at self government. After years of unrest and rebellion, the Spanish left Mexico, leaving a land in turmoil.