From The Boston Store To Corregidor: Fort Smith Man Did A Yeoman’s Job In World War II

By Chad Davis

In one form or another, the idiom “a yeoman’s job” pervades the anglophone world as a phrase to describe “very good, hard, and valuable work that someone does especially to support a cause, to help a team, etc.”[2] The dictionary defines a yeoman in various ways, from “a person who owns and cultivates a small farm” to “a naval petty officer who performs clerical duties.”[3] The United States (US) Naval Institute describes the enlisted yeoman rating as one of the most “enduring” to serve on our country’s Navy combat team.[4] Because nearly all types of Navy units require a yeoman, Sailors of that particular rating can be found serving in virtually any wartime scenario. Throughout World War II, one petty officer of the US Navy, Chief Yeoman Theodore Richard Brownell (1905-1990) of Fort Smith, Arkansas, served his country in ways that epitomize a yeoman’s job ― as well as another phrase associated with his home town: true grit.

In one form or another, the idiom “a yeoman’s job” pervades the anglophone world as a phrase to describe “very good, hard, and valuable work that someone does especially to support a cause, to help a team, etc.”[2] The dictionary defines a yeoman in various ways, from “a person who owns and cultivates a small farm” to “a naval petty officer who performs clerical duties.”[3] The United States (US) Naval Institute describes the enlisted yeoman rating as one of the most “enduring” to serve on our country’s Navy combat team.[4] Because nearly all types of Navy units require a yeoman, Sailors of that particular rating can be found serving in virtually any wartime scenario. Throughout World War II, one petty officer of the US Navy, Chief Yeoman Theodore Richard Brownell (1905-1990) of Fort Smith, Arkansas, served his country in ways that epitomize a yeoman’s job ― as well as another phrase associated with his home town: true grit.

In some official Navy publications, Theodore’s background has been obscured by legends. For instance, the January 1967 issue of All Hands states that he descended from Commodore Matthew Perry.[5] Although the two could in fact be distantly related, as they both descended from old colonial families of Massachusetts, Commodore Perry is not an ancestor of Theodore. Likewise, the November 1978 issue of Campus claimed that Theodore was a member of the ninth generation “of the sea-faring Brownell family” to have served in the US Navy, with the only exception being his father, “who was a merchantman who went to sea.”[6] Perhaps nine generations had passed since the Brownells sailed from England to Massachusetts and Rhode Island, where they are listed in many early sources as yeomen (farmers). Having descended from a Wisconsin pioneer branch of the Brownell family, Theodore’s ancestors mostly farmed. Theodore did, however, have a grandfather who served as a private in the 24th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. The immense suffering endured by Private Charles Franklin Brownell (1838-1898) in service to his country―as a prisoner of war (POW) at the infamous Confederate Camp Sumter Military Prison by Andersonville, Georgia―foreshadows ominously in the story of Charles’ grandson, Theodore.

Charles’ son, Oscar William Brownell (1867-1944), married Ella Gertrude McGinty (1866-1933) in 1890. Oscar and Ella moved from Wisconsin to Saint Louis, Missouri, prior to 1910. Whereas the census of that year places the birth of Ella in the state of Indiana, the records of 1920 and 1930 place Ella’s birth in Ohio. According to the 1910 census, Ella’s parents emigrated from Ireland, although the census of 1930 places the birth of Ella’s mother in England. In 1910, Oscar worked as an engineer at a Saint Louis brewery, while Ella cared for their daughter Helen (born 1903) and younger son Theodore. Helen and Theodore were both born in Missouri. According to his 1928 marriage license, as well as the census records of 1910 and 1920, Theodore’s birth is dated to 1907. However, his death certificate gives a birth date of September 6, 1905.

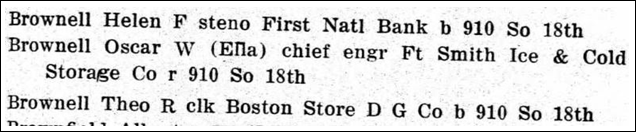

Oscar, Ella, Helen, and Theodore moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma before settling in Fort Smith after 1912. According to the 1928 Fort Smith city directory, Oscar worked as the Chief Engineer at Fort Smith Ice and Cold Storage, Helen worked as a stenographer at First National Bank, and Theodore worked as a clerk at Fort Smith’s iconic Boston Store―the “source for finer things in Western Arkansas.”[7]

Fort Smith City Directory, 1928 [8]

Theodore joined the Navy in 1922. Although much of the US military stood down following the conclusion of World War I, the Navy continued to expand, largely through the Naval Reserve Force, created in 1915 on the initiative of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt. In the Naval Reserve Force, Sailors continued living as civilians, for the most part, while prepared to deploy in case another war began.

On March 28, 1928, Theodore married Catherine Bell Murrey (1906-1969), who was born in Fort Smith to parents from Ohio. When Theodore transferred to Active Duty in the 1930s, he and Catherine traveled the world together, and lived in some of the most exotic places. Catherine gave birth to their son, Richard Murrey Brownell (1930-2020), nine months after she joined Theodore in the Territory of Hawaii. The following August, Catherine gave birth to another son, Jack Delaney Brownell (1931-2014). Theodore reenlisted in San Diego, California on April 10, 1936, before transferring to the Philippines. Richard later recalled how he learned to swim in the Philippines before World War II began, at which point he “ended up going to Fort Smith, Arkansas, where he spent time on his grandparents’ farm birthing calves and going to school at a Benedictine monastery.”[9]

With war approaching in the summer of 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt federalized all military forces in the Philippines, recalled US Army General Douglas MacArthur to active duty, and placed the general in command of all US Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). The US Navy also began shuffling around its forces in the South Pacific, which fell under the overarching authority of the Commander-in-Chief of the Asiatic Fleet, Admiral Thomas Hart. Admiral Francis Rockwell commanded the 16th Navy District, which consisted of all Navy installations and forces in the Philippines. One such force of the 16th Navy District, the Inshore Patrol, had the responsibility of safeguarding Manila Bay. The Inshore Patrol operated out of Cavite Navy Yard, located southwest of Manila. The Asiatic Fleet operated out of Cavite, as well as the bases at Olongapo in Subic Bay, and Mariveles on the southern tip of the Bataan Peninsula. In the mouth of the bay, across the northern channel from Bataan, stood the tadpole-shaped island fortress of Corregidor.

US Marine Corps map of Luzon Island showing the locations of Olongapo in Subic Bay, Mariveles on the southern tip of the Bataan Peninsula, Cavite Navy Yard southwest of Manila in the bay, and Corregidor in the mouth of the bay.[10]

Theodore worked in the receiving station at Cavite Navy Yard when he reenlisted for four years on April 10, 1940. He then transferred to the navy yard staff. Following a period of temporary attached duty onboard the USS Vaga (YT 116), a harbor tug, from March to October 1 of 1941, Theodore received orders to report to the Inshore Patrol on October 10, 1941.

With the Japanese closing in that November, Admiral Hart finally ordered the withdrawal of the “China Marines.” The 4th Marine Regiment, commanded by Colonel Samuel Howard, had been stationed in Shanghai, China for many years until Admiral Hart ordered their relocation to Olongapo, Philippines. Not wishing to lose an entire Marine regiment in a hopeless last stand, Admiral Hart and Colonel Howard had conspired for months to pull the Marines out of China without orders from Washington, DC. Instead of replacing the China Marines who rotated out of Shanghai, Admiral Hart sent their replacements to Cavite Navy Yard, where they constituted the 1st Separate Marine Battalion.[11] When the 4th Marine Regiment arrived in the Philippines, its 1st and 2nd Battalions absorbed into their ranks the Marines of the Olongapo barracks. While the regiment’s 2nd Battalion remained at Olongapo, and the 1st Separate Marine Battalion remained at Cavite, Admiral Rockwell ordered the regiment’s 1st Battalion to defend the base at Mariveles. The 1st Battalion deployed from Olongapo to Mariveles onboard the USS Vaga just hours after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.[12] Although Japan began attacking the Philippines that same day, while the Marines sailed onboard the USS Vaga with no support, the 1st Battalion arrived at Mariveles without incident.

The Japanese concentrated their first attacks in the Philippines on the task of knocking out Allied air power before it could get off the ground. Japanese bombers, which flew well above the reach of Allied antiaircraft guns, returned December 10 to obliterate Cavite Navy Yard, then again on December 19 to finish what they missed. By Christmas, General MacArthur ordered Allied troops to fall back to Bataan, where they could effectively hold a line against the Japanese while protecting the mouth of Manila Bay. The 1st Separate Marine Battalion sabotaged anything left intact at Cavite Navy Yard and then departed for Bataan, where they officially mustered in as the 3rd Battalion of the 4th Marine Regiment. Likewise, the 2nd Battalion helped sabotage Olongapo. All vessels remaining at Cavite and Olongapo then transferred to the Inshore Patrol and moved to Corregidor and Mariveles “to oppose the movement by water of Japanese men and material along the shores of Manila Bay.”[13]

Japan’s attack on the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor succeeded in cutting off the Asiatic Fleet from supplies and reinforcements. Following a string of defeats in the desperate bid to prevent Japan’s invasion of the Philippines―to stall Japan’s conquest of the entire South Pacific―the severely outgunned Asiatic Fleet lost half of its ships before falling back to Australia. Japan slammed fresh waves of invaders against the Allied defenders of Bataan, who fought nonstop for months, as a host of exotic diseases began to set in due to dwindling supplies of medicine and food rations. Admiral Hart abandoned the Philippines in January, and Admiral Rockwell departed with General MacArthur in March. The USAFFE command ceased to exist, and Major General Jonathan Wainwright IV, Commander of the US Army Philippines Department, took command of all remaining Allies from his headquarters in the tunnel complex deep within Malinta Hill, on the island of Corregidor. The tunnels filled with wounded troops, and soldiers who belonged to units destroyed on Luzon Island. The 4th Marine Regiment moved across the channel and assumed the task of defending Corregidor’s beaches. After running Japan’s blockade on light motor patrol boats at night, upon his safe arrival in Australia, General MacArthur famously promised to return. Bataan fell on April 9, and Corregidor fell on May 6, 1942.

General MacArthur again waded ashore in the Philippines on October 20, 1944. Not one year later, onboard the USS Missouri (BB 63) in Tokyo Bay, Generals MacArthur and Wainwright personally accepted the unconditional surrender of Japan on September 2, 1945. General MacArthur proceeded to rule the defeated empire as its military dictator. He made many important decisions during the occupation of Japan, such as retaining the emperor as his own subordinate. General MacArthur also upheld the convictions, sentences, and executions of many Japanese military and government officials for war crimes.

George Weller: Hell-Ship Japs Denied Yanks Water Even For Baptisms For The Dying, But Sold Driblets For Wedding Rings.[14]

So horrific were the details of Japan’s atrocities that General MacArthur also heavily censored the press. George Weller, a Pulitzer Prize-winning war correspondent, defected from the press corps in August, 1945. Going rogue, Weller became the first American to see the devastation of the nuclear attacks from the ground. He also extensively interviewed liberated Allied POWs. Until the publishing of First Into Nagasaki: The Censored Eyewitness Dispatches on Post-Atomic Japan and Its Prisoners of War, Weller’s primary account had been suppressed for many decades. As Walter Cronkite explained in the foreword of First Into Nagasaki, Weller’s dispatches “were censored and destroyed by General MacArthur. Weller salvaged his carbon copy but, in his subsequent travels to many corners of our troubled globe, the copy disappeared. His son, an honored writer in his own right, has only recently uncovered it and this book is the result.”[15] Though censored by General MacArthur, newspapers across the US published some of Weller’s dispatches, which nonetheless succeeded in painting a very grim picture of Japan’s brutality against Allied POWs.

When Bataan fell on April 9, nearly 80,000 Allied POWs began a ten-day forced march of sixty-six miles, with little water or food. Japanese troops randomly beat the prisoners along the way, and murdered several by bayonet or beheading. The prisoners marched from Mariveles to San Fernando, and were “then taken by rail in cramped and unsanitary boxcars farther north to Capas. From there they walked an additional 7 miles to Camp O’Donnell.” Only 54,000 POWs survived the Bataan Death March.[16] After a few months, the prisoners moved to the camps at Cabanatuan.

Meanwhile the Allies who held out on Corregidor endured the same lack of medicine and food rations as those on Bataan, and the same diseases ravaged the Allies on Corregidor, who also withstood a brutal and unceasing artillery assault, which blanketed the small island from all sides. While thousands of troops who evacuated from Bataan suffered the heat and foul air of the tunnel complex beneath Malinta Hill on Corregidor, the 4th Marine Regiment remained scattered across the beaches of the tiny island, awaiting the inevitable Japanese invasion, while constantly under fire.

According to his Prisoner of War Medal citation, Yeoman First Class Theodore Richard Brownell, “a former crewman of the [USS Canopus] (AS-9), was captured by the Japanese after the fall of Corregidor, Philippine Islands, on 6 May 1942.”[17] In a hazing far worse than any modern chief petty officer-selectee could imagine, Theodore earned his promotion to Chief Yeoman while he stayed, in his own words, as “a guest of the emperor.”[18] Although the details of his service in the Battles of Bataan and Corregidor are lost to posterity, much can be discerned from the fact that he penultimately transferred to the USS Canopus. When Bataan fell, the Canopus Sailors were only allowed onto Corregidor because they agreed to remain on the beaches―to fight alongside the Marines.

The USS Canopus, with submarine squadron.[19]

The USS Canopus belonged to the Asiatic Fleet’s Submarine Squadron 20. A submarine tender, the USS Canopus operated out of Cavite Navy Yard and supplied its squadron of submarines with various stores. The machine shops onboard could fabricate any part for repairs. When Admiral Hart ordered the Asiatic Fleet out of the Philippines, he selected the USS Canopus to stay behind. A submarine tender needed to remain in Manila Bay, as the Navy continued to smuggle out high-ranking officers and civilians beneath Japan’s blockade. After General MacArthur abandoned Manila and ordered all Allied forces on Luzon Island to fall back to Bataan, the USS Canopus transferred to the Inshore Patrol and shifted to Mariveles on Christmas Day. The Inshore Patrol most likely assigned Theodore to the USS Canopus at this time.

On 29 December 1941 and 1 January 1942, she received direct bomb hits which resulted in substantial damage to the ship and injuries to 13 of her men. Working at fevered pace, her men continued to care for other ships while keeping their own afloat and in operation. To prevent further Japanese attack, smoke pots were placed around the ship and the appearance of an abandoned hulk was presented by day, while the ship hummed with activity by night.[20]

Both the US Army and the US Navy operated minefields in the mouth of Manila Bay. The approach to Mariveles by water was relatively secured by the mines and the guns of Corregidor. To take Bataan, the Japanese pushed south through the east-west front line that ran across the north of the peninsula. While the Canopus Sailors abandoned their ship throughout the day, they also served in the Provisional Naval Battalion, which “included some 500 U.S. sailors and their officers, evacuated from bombed-out naval facilities.”[21] The Sailors “dyed their uniforms with coffee grounds, hoping for khaki but getting yellow instead. A startled Japanese officer wrote in his diary that he had seen ‘a new type of suicide squad dressed in brightly colored uniforms.‘”[22] Before transferring to Corregidor, the 4th Marine Regiment left “120 Marines organized into two antiaircraft batteries based at Mariveles.”[23] Some of these Marines joined the Provisional Naval Battalion to train and lead the Sailors in ground combat operations.

The Japanese attempted a landing behind the Bataan main line on the night of January 22-23, 1942. The landing craft ran into trouble, and in the end nearly three hundred troops blundered ashore near Mariveles. Over the next week, Marines from the antiaircraft batteries, sailors and Marines from the naval battalion, and even Army Air Corps pilots and groundcrew serving as infantry ran these tenacious Japanese to ground, then supported U.S. Army and Philippine Scout units that ground them to dust.[24]

In February, fifty-eight Canopus Sailors moved to Corregidor to form a reserve company for the 4th Marine Regiment. “Lieutenant Clarence Van Ray with Platoon Sergeant Leslie D. Sawyer and Sergeant Ray K. Cohen trained and equipped the sailors into an efficient fighting force. Ten Marines and 40 more sailors were added to the company after the fall of Bataan.”[25]

When the Army surrendered Bataan, most of the remaining Marines escaped to Corregidor. The USS Canopus backed out “under her own power, battle ensigns flying, into deep water,” where the crew scuttled their own ship.[26] The battle-hardened Canopus Sailors who escaped Bataan then joined their shipmates who had already crossed over to train with the Marines on Corregidor. The Sailors soon formed the backbone of an entirely new unit, one of the most peculiar formations in US Navy and Marine Corps history: the 4th Battalion of the 4th Marine Regiment.

With Bataan on the brink of falling, Captain John H. S. Dessez, the commander of the Navy Base at Mariveles requested permission to transfer his 500 sailors to Corregidor. Approval was granted with the condition that these men would be part of the beach defense force. On 10 April, the 4th Battalion was formed under the command of Major Francis H. “Joe” Williams. . . This joint service battalion bivouacked in Government Ravine near Battery Geary and began to train for ground combat.[27]

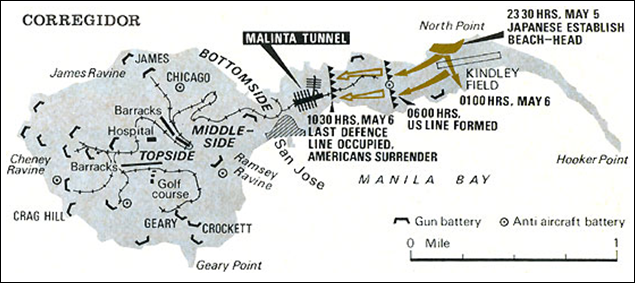

The Battle of Corregidor, May 5-6, 1942.[28]

The 2nd Battalion defended the mountainous western sector, the 3rd Battalion took the middle sector, and the 1st Battalion took the eastern sector from Malinta Tunnel to Hooker Point. The 4th Battalion organized into Companies Q, R, S, and T. Army officers commanded Companies Q and R, while Navy officers commanded Companies S and T. Their rifles “were all that was issued to the battalion in the way of equipment. There were no helmets, cartridge belts, or even first aid kits.”[29] Major Williams “at once began weapons training for his sailors. With no rifle range available, the blue-jackets used floating debris in Manila Bay as targets on which to sight in their rifles.”[30]

After softening up the island with weeks of intense, constant bombardment, Japan launched the invasion of Corregidor on the night of May 5. The 1st Battalion suffered heavy casualties in the fierce shelling which immediately preceded the landings. The shelling obliterated any remaining barriers and traps constructed on the beaches by the Marines. The 1st Battalion disabled several landing craft, killing scores of Japanese troops, who nevertheless successfully landed at North Point near Kindley Field, established a beachhead, and fought their way through the 1st Battalion to take the high ground at the battery on Denver Hill. Believing that a larger, main assault could attack to the west, Colonel Howard left the 2nd and 3rd Battalions in place. Shortly before midnight, he placed the 4th Battalion on alert and deployed the regimental reserve to Malinta Tunnel. “Major Max W. Schaeffer commanded the regimental reserve, which consisted of two companies lettered O and P, formed mainly from Headquarters and Service Company’s personnel.”[31]

At 0100 Major Schaeffer gave his company and platoon commanders orders to counterattack and drive the Japanese off the tail of Corregidor. Company P would advance down the road toward Kindley Field and upon meeting resistance would deploy to the left of the road while Company O would move to the right. Together the companies would sweep to the end of the island. Officers of the 1st Battalion would lead the two companies into position. At 0200 the two companies of the regimental reserve deployed down the road leading east from Malinta Tunnel.[32]

The Japanese dug in on Denver Hill and stalled the advance of the regimental reserve. Colonel Howard ordered Major Williams to move his 4th Battalion to Malinta Tunnel at 0130. The battalion “marched in the darkness in two columns along the road to the tunnel well spread out to avoid Japanese artillery fire, but were delayed by a 20-minute artillery barrage and suffered a few casualties. By 0230, Major Williams had his men in Malinta Tunnel and awaited further orders.”[33]

At 0430 Colonel Howard decided to commit his last reserves, the 500 Marines, sailors, and soldiers of the 4th Battalion. Major Williams’ men were long ago ready to move out, the Malinta Tunnel being severely congested with a constant stream of wounded Marines from the early fighting. Morale in the battalion was strained by the constant concussions from the Japanese shelling outside and the proliferation of rumors in the tunnel. Lieutenant Charles R. Brook, USN, remembered, “It was hot, terribly hot, and the ventilation was so bad that we could hardly breathe.”

Led by Major Williams, the battalion emerged from the tunnel in platoon column. The men were suddenly subjected to a severe shelling and casualties began to mount before the last company was able to leave the tunnel. However, within 10 minutes, the battalion reformed under fire and began to move forward. Another barrage soon struck, causing more casualties and confusion. Minutes later, the column was again reorganized and the advance continued. At 200 yards behind the line of the 1st Battalion, Williams ordered Companies Q and R to deploy in a skirmish line and guide to the left of the line. Company T repeated the orders and formed on the right of Company R and guided to the right. Company S formed the reserve.

The order of the battalion was prudent, for the main line of resistance was badly in need of reinforcement. In the moonlight, deployment into skirmish formation was difficult, but eventually accomplished. Contact with the 1st Battalion was spotty at best and no Marines were found in line ahead of Company R. Scattered parties of Japanese soldiers had infiltrated behind the Marine positions all night and their sniping proved worrisome to the inexperienced sailors. Both Companies Q and R were receiving fire from ahead and behind as they moved into position.[34]

Led by Major Williams, the battalion emerged from the tunnel in platoon column. The men were suddenly subjected to a severe shelling and casualties began to mount before the last company was able to leave the tunnel. However, within 10 minutes, the battalion reformed under fire and began to move forward. Another barrage soon struck, causing more casualties and confusion. Minutes later, the column was again reorganized and the advance continued. At 200 yards behind the line of the 1st Battalion, Williams ordered Companies Q and R to deploy in a skirmish line and guide to the left of the line. Company T repeated the orders and formed on the right of Company R and guided to the right. Company S formed the reserve.

The order of the battalion was prudent, for the main line of resistance was badly in need of reinforcement. In the moonlight, deployment into skirmish formation was difficult, but eventually accomplished. Contact with the 1st Battalion was spotty at best and no Marines were found in line ahead of Company R. Scattered parties of Japanese soldiers had infiltrated behind the Marine positions all night and their sniping proved worrisome to the inexperienced sailors. Both Companies Q and R were receiving fire from ahead and behind as they moved into position.[34]

Fresh Japanese reinforcements landed just before dawn. Major Williams and his four company commanders spent the time between 0530 and 0600 getting the 4th Battalion into position. At 0600, Major Williams ordered the 4th Battalion “to counterattack at 0615, the break of dawn.” When the order came down, “the Marines, sailors, and soldiers charged with fixed bayonets, ‘yelling and screaming . . . cursing and howling.’”[35] Companies Q and R took ground on the left, but the advance of Companies S and T quickly ground to a halt under heavy machine gun fire. Japanese troops on Corregidor “sent up flares which brought a prompt response from the artillery on Bataan. In 10 minutes the gunfire halted and Company T resumed the attack on the ground around Battery Denver, but machine gun fire quickly halted the advance.”[36]

During the morning action Major Williams fought beside his men, moving from position to position along the line. Captain Brook remembered, “He was everywhere along the line, organizing and directing our attack, always in the thick of it, seeming to bear a charmed life. I have heard men say that he was the bravest man they ever saw.”

From 0900 until 1030 the fire fight proceeded without change in position. The lines were so close that none of the companies could shift a squad without drawing machine gun fire and artillery. All of the 4th Battalion was fighting without helmets, canteens, or even cartridge belts.[37]

From 0900 until 1030 the fire fight proceeded without change in position. The lines were so close that none of the companies could shift a squad without drawing machine gun fire and artillery. All of the 4th Battalion was fighting without helmets, canteens, or even cartridge belts.[37]

The initiative turned against the invaders, as the Japanese troops began running low on ammunition. The attack of the 4th Battalion successfully destroyed Japanese mortar and machine gun positions. Unfortunately for the Allied defenders, the Japanese successfully landed three tanks on Corregidor at dawn. Initially “prevented from moving inland by the slope behind the beach,” a “captured M-3 negotiated the cliff and succeeded in towing the remaining tanks up the cliff. By 0830, all three tanks were on the coastal road and moved cautiously inland.”[38]

At 1000 Marines on the north beaches watched as the Japanese began an attack with their tanks, which moved in concert with light artillery support. Private First Class Silas K. Barnes fired on the tanks with his machine gun to no effect. He watched helplessly as they began to take out the American positions. He remembered the Japanese tanks’ guns “looked like mirrors flashing where they were going out and wiping out pockets of resistance where the Marines were.” The Marines still had nothing in operation heavier than automatic rifles to deal with the enemy tanks.[39]

Casualties began to mount. The wounded who could walk made their way back to Malinta Tunnel under heavy artillery fire, but no one “could be spared from the line to take the wounded to the rear.”[40]

At 1030 the pressure from the Japanese lines was too great and men began to filter back from the firing line. Major Williams personally tried to halt the men but to little avail. . . The tanks fired on Marine positions knocking them out one by one. At last Williams ordered his men to withdraw to prepared positions just short of Malinta Hill.

With the withdrawal of the 4th and 1st Battalions, the Japanese sent up a green flare as a signal to the Bataan artillery which redoubled its fire, and all organization of the two battalions ceased. Men made their way to the rear in small groups and began to fill the concrete trenches at Malinta Hill. The Japanese guns swept the area from the hill to Battery Denver and then back again several times. In 30 minutes only 150 men were left to hold the line.

The Japanese had followed the retreat aggressively and were within 300 yards of the line with tanks moving around the American right flank. . . At 1130 Major Williams returned to the tunnel and reported directly to Colonel Howard that his men could hold no longer. He asked for reinforcements and antitank weapons. Colonel Howard replied that General Wainwright had decided to surrender at 1200. Wainwright agonized over his decision and later wrote, “It was the terror vested in a tank that was the deciding factor. I thought of the havoc that even one of these beasts could wreak if it nosed into the tunnel.” Williams was ordered to hold the Japanese until noon when a surrender party arrived.

At 1200 the white flag came out of the tunnel and Williams ordered his men to withdraw to the tunnel and turn in their weapons. The end had come for the 4th Marines. Colonel Curtis ordered Captain Robert B. Moore to burn the 4th Marines Regimental colors. Captain Moore took the colors in hand and left the headquarters. On return, with tears in his eyes, he reported that the burning had been carried out. Colonel Howard placed his face into his hands and wept, saying, “My God, and I had to be the first Marine officer ever to surrender a regiment.”[41]

With the withdrawal of the 4th and 1st Battalions, the Japanese sent up a green flare as a signal to the Bataan artillery which redoubled its fire, and all organization of the two battalions ceased. Men made their way to the rear in small groups and began to fill the concrete trenches at Malinta Hill. The Japanese guns swept the area from the hill to Battery Denver and then back again several times. In 30 minutes only 150 men were left to hold the line.

The Japanese had followed the retreat aggressively and were within 300 yards of the line with tanks moving around the American right flank. . . At 1130 Major Williams returned to the tunnel and reported directly to Colonel Howard that his men could hold no longer. He asked for reinforcements and antitank weapons. Colonel Howard replied that General Wainwright had decided to surrender at 1200. Wainwright agonized over his decision and later wrote, “It was the terror vested in a tank that was the deciding factor. I thought of the havoc that even one of these beasts could wreak if it nosed into the tunnel.” Williams was ordered to hold the Japanese until noon when a surrender party arrived.

At 1200 the white flag came out of the tunnel and Williams ordered his men to withdraw to the tunnel and turn in their weapons. The end had come for the 4th Marines. Colonel Curtis ordered Captain Robert B. Moore to burn the 4th Marines Regimental colors. Captain Moore took the colors in hand and left the headquarters. On return, with tears in his eyes, he reported that the burning had been carried out. Colonel Howard placed his face into his hands and wept, saying, “My God, and I had to be the first Marine officer ever to surrender a regiment.”[41]

The 2nd and 3rd Battalions stood ready to fight at the time of surrender, but the Marines had to follow the orders of General Wainwright. After the surrender, Japanese troops herded the 13,000 Allied POWs onto a small concrete pad called the 92nd Garage Area, where they spent three days exposed to the sun without food, water, or sanitation. Eventually the Japanese gave each prisoner a small serving of rice, and one canteen of water per day. On May 23, the “POWs marched to the South Dock where they were taken by launch to Japanese transports.”[42] The prisoners continued boarding the transports until the next morning, at which time they sailed to the city of Pasay, just south of Manila.

…landing barges ferried the men to shore, stopping short, giving the Japanese yet another opportunity to humiliate the prisoners. As Jack Wright of the 91st Coast Artillery remembered: “The landing barges moved in toward the beach until in water about four feet deep. The ramps were lowered, and we were ordered to go into the water from waist deep to shoulder deep.” The men slogged ashore, struggling to keep their meager possessions dry by holding them up over their heads, their already tattered clothing now soaked and filthy.[43]

The Japanese then ordered the Allied POWs to form up into columns for a humiliating parade through the streets of Manila, known as the March of Shame. The terminus of the parade, Bilibid Prison, “was a vast prison complex built by the Spanish in 1865 on seventeen acres of land in the middle of Manila.” A “compound designed for 5,200,” Bilibid Prison quickly proved to be inadequate for the number of Allied POWs captured in the Philippines.[44] The Japanese soon began dispersing the POWs to slave labor camps throughout their empire.

For many years, a Naval Education and Training manual titled Captivity: the Extreme Circumstance, has included details of Theodore’s imprisonment. He served as the “Camp Sergeant Major for the Cabanatuan Prison Camp [Number] 1.” As such, he helped facilitate the work of captive Allied chaplains. “The programs for religious services were prepared in my office,” he explained. “I took care of passes through to our ‘makeshift’ hospital for chaplains and all.”[45] The Allied POWs constructed a thatched tabernacle used for Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish services. Catholic chaplains performed Mass every day, and Protestant chaplains held Bible classes at night.

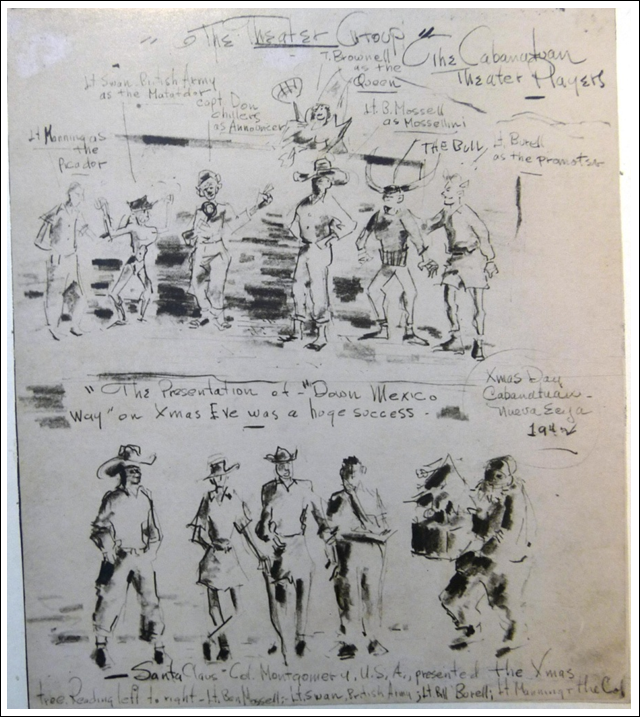

Besides the religious services he helped facilitate, Theodore also played a crucial role in the formation of the “entertainment unit” as a member of the Cabanatuan Theater Players, whose Christmas Eve, 1942 production of the 1941 Gene Autry film Down Mexico Way reportedly “was a huge success.”[46] Theodore presented the show, in drag, “as the Queen.”

The Cabanatuan Theater playbill, 24 December 1942.[47]

…the American prisoners, most of whom were in a constant state of fatigue and exhaustion anyway, as a result of too little food and an excess of anxiety and strain, had little time for recreation. Nor was there much opportunity to indulge in it. And, to tell the truth, many of them, in their weakened and despairing state, had little desire to amuse themselves. Fortunately, however, there were those among them whose knowledge of human psychology made them realize how important it was for the men to have something outside of the common routine of their daily existence to divert their minds from the unpleasantness and unhappiness of their existence. It was largely due to the efforts of these few wise ones that the prisoners at Cabanatuan made definite and concerted efforts to promote every form of recreation available to them, and to manufacture others, in an attempt to lift their morale, and to keep them from sinking into the lethargy of complete despair. How well they succeeded is witnessed by the variety of amusements which they managed to contrive in spite of their limited resources, and even more by the amazingly high morale of the majority of the men throughout the three years of their imprisonment. . . it must not be forgotten that the men at this camp were not a selected group. They were a true cross-section of American life. Among them were people of all degrees of wealth, education and culture, from the highest to the lowest. Every occupation and profession were represented here, every type of personality, every shade of opinion, political, social and religious. The entertainment unit continued to function throughout 1944, although some of the projects it had initiated, notably the camp band, suffered considerably from the loss of personnel by death, as well as by shipment to Japan. It did, however, accomplish its purpose of keeping the prisoners’ morale at a reasonably high level during these difficult days.[48]

In late 1944, Japan began to settle on a final solution for the Allied POWs. In areas where Japanese forces were being forced to retreat, the prisoners would either be shipped to the Japanese home islands, or exterminated en masse. This included some of the Canopus Sailors, who had transferred from Cabanatuan to build an airstrip for the Japanese by the city of Puerta Princessa in the Philippine Province of Palawan. The prisoners had been forced to dig their own bomb shelters, which consisted of small, covered trenches, roughly five feet deep. The prisoners dug one of the trenches close enough to the barbed wire perimeter so that they could loosen some rock and escape down the surrounding cliff, if given the opportunity.

On December 14, 1944, the Japanese guards sounded the air raid siren to lure the prisoners into their shelters. The Japanese fixed bayonets and surrounded the shelters with machine guns, before dumping barrels of fuel into the shelters at both ends, and then tossing in lit torches. The machine guns mowed down many of the prisoners who escaped, some of whom ran from the shelters engulfed in flames. Dozens of men escaped from the shelter by the cliff. When the Japanese discovered the hole, they hunted down the escapees like wild game. Marine Corps Sergeant Glenn “Mac” McDole survived the Palawan Massacre by tunneling to the bottom of a “huge pile of garbage and refuse which had been growing higher and higher during his years in captivity.”[49]

The smell nearly suffocated Mac as he dived into what was normally home for the island’s vermin. Ordinarily, just a whiff of the dump would cause a man to gag, but there was little time to spare, and Mac started digging into it . . . doing his best to ignore the overpowering stench. At times he almost vomited, but he knew it was not the time to get sick. . .

By now, the guards were on the beach en force, and Mac could hear them talking. Then the shooting began, as they found prisoners among the rocks and in the small coral caves. . .[50]

Mac wanted to run, but something kept telling him to stay put. He did, all the while praying to God to give him the strength to survive. As he prayed, he could hear the laughter of the guards and smell the stench of burning flesh. The odor of flesh burning and the garbage was overwhelming, but he managed again to fight off a powerful urge to vomit. There were other sounds along the beach: screams of other POWs as they were bayoneted, burned, beaten, and shot, then the laughter of the guards as they set fire to the living and the dead. Then it was quiet, very quiet.[51]

By now, the guards were on the beach en force, and Mac could hear them talking. Then the shooting began, as they found prisoners among the rocks and in the small coral caves. . .[50]

Mac wanted to run, but something kept telling him to stay put. He did, all the while praying to God to give him the strength to survive. As he prayed, he could hear the laughter of the guards and smell the stench of burning flesh. The odor of flesh burning and the garbage was overwhelming, but he managed again to fight off a powerful urge to vomit. There were other sounds along the beach: screams of other POWs as they were bayoneted, burned, beaten, and shot, then the laughter of the guards as they set fire to the living and the dead. Then it was quiet, very quiet.[51]

Sergeant McDole and ten other men successfully evaded the Japanese and found their way to friendly Filipino guerrilla fighters. Reports of the Palawan Massacre soon reached General MacArthur, who decided to make a priority out of liberating the prison camps before the Japanese could exterminate any more Allied POWs. General MacArthur needed a force that could infiltrate deep behind enemy lines.

The US Army began organizing Ranger Battalions in 1942, starting with Company A of the 1st Ranger Battalion, commanded by Captain William Darby, who was born, and is buried, in Fort Smith. Darby rose to the rank of brigadier general after giving his life to the Allied cause in Italy. The Rangers made great sacrifices in their effort to liberate Cisterna; Fort Smith’s sister city. In the Pacific War, General MacArthur made use of the 6th Ranger Battalion, which in October of 1944 became the first Army ground unit to return to the Philippines. On January 30, 1945, the 6th Ranger Battalion launched the first assault on a Japanese prison camp. The operation, which successfully liberated the prisoners at Cabanatuan, is popularly known as the Great Raid.[52]

Unfortunately for Theodore, the assault came a month too late. In early December, he and thousands of other prisoners departed from Cabanatuan, and returned to Bilibid Prison in Manila. From there, they awaited their turn to sail to Japan onboard the infamous hell ships―the unmarked Japanese cargo vessels which transported Allied POWs to Japan. On these voyages, known as death cruises, the hell ships proved to be especially susceptible to attack because “Allied sub commanders and pilots had no way of knowing if the ships they were attacking carried POWs.”[53]

The prisoners, packed tightly into the holds below deck, stood together without enough room to move or sit down. Breathable air was minimal, and many prisoners died of suffocation and exhaustion. Some prisoners were murdered by their fellow POWs for a drink of water, for a drink of blood, or for an extra few inches of space to occupy. Only after the deaths of many prisoners did the others have room to sit down, or to lay among the dead, and rest upon the steel decks, which quickly transformed into open sewers. “A whole bay full of interlocked men would dispute loudly over such a matter as when to turn over and rest on the other side. All had to turn or none; there was not room for differing postures.”[54]

Many of the hell ships delivered cattle to the Philippines before taking the Allied POWs into their holds; the decks of which remained covered in manure. In one such hell ship, the Enoura Maru, a previous load of “horses had been fed oats, and the starve-crazed men scratched through the droppings in search of single, undigested grains to eat.”[55] The voyage of the Enoura Maru, from the Philippines to Formosa, represented but one leg of a notoriously tragic death cruise.

The first leg of the voyage took place onboard the hell ship Oryoku Maru, from Manila to Olongapo, where many “men lost their minds and crawled about in the absolute darkness armed with knives, attempting to kill people in order to drink their blood or armed with canteens filled with urine and swinging them in the dark.”[56] As Weller wrote of the prisoners who boarded the Oryoku Maru in Manila, upon their arrival to Japan, the “pitiful handful left were hardly men. Once civilized beings, they now were little more than animals fighting the great, ultimate fight for survival.”[57] Theodore lived to tell about it:

On the 13th of December 1944, the Japanese marched 1,639 officers and men from Bilibid Prison to Pier 7, Manila, Philippine Islands. A roundabout way was selected to help humiliate we prisoners in the eyes of the Filipinos and Japanese Military in Manila. The day was a scorching-hot one and the march was not an easy one for men in the poor physical condition which then prevailed in our ranks. We were loaded like cattle into the forward and after hold of the ship the Oryoku Maru. It was just a matter of hours before many deaths resulted from heat exhaustion and suffocation.

. . . off Olongapo, Philippine Islands, the ship was strafed by the American flyers and eventually bombed. Many officers and men were killed instantly or suffered major wounds when a bomb exploded at the base of the mainmast. Part of the mast fell into the hold and, together with hatch covers, numerous men were buried in the debris.[58]

. . . off Olongapo, Philippine Islands, the ship was strafed by the American flyers and eventually bombed. Many officers and men were killed instantly or suffered major wounds when a bomb exploded at the base of the mainmast. Part of the mast fell into the hold and, together with hatch covers, numerous men were buried in the debris.[58]

The prisoners in the hold of the Oryoku Maru who could escape then had to jump overboard. Japanese soldiers along the shoreline watched as prisoners swam ashore, and then showered the swimming prisoners with a hail of bullets. When they too realized that the Oryoku Maru was sinking, the Japanese troops ceased fire, and herded the survivors onto a tennis court, where the prisoners sat for days in the sun, waiting for the next move. Theodore continued:

A couple of miserable days were spent on a tennis court in plain sight of attacking planes and then we were loaded into trucks and transported to a theater in San Fernando, Pampanga, on the Island of Luzon again. A couple of miserable days and nights spent in cramped positions but, for a change, a little more rice in our stomachs, we were loaded into oriental-type (small) boxcars like cattle. Men again met death on a crawling trip to San Fernando, La Union, from heat exhaustion and lack of water. I recall that my buddy, William Earl Surber, [US Army] (now deceased), took turns sucking air through a little bolt hole in the rear of the car we were packed into.

This miserable train ride ended at San Fernando, La Union, still on the Island of Luzon. This was on Christmas Eve. The following day we were marched into a schoolyard where we were furnished with a more plentiful portion of rice and limited supply of water. That night we were herded into ranks and marched to another point several kilometers away and placed on the sands of a beach. We waited there all that following day and night in the hot sun while horses were being unloaded from some Japanese ships. The next day, men and officers dying from the usual causes (dysentery mostly) were loaded into the forward and after holds of these cattle carriers for the second leg of a trip (beyond the belief of people in our so-called civilized age).[59]

This miserable train ride ended at San Fernando, La Union, still on the Island of Luzon. This was on Christmas Eve. The following day we were marched into a schoolyard where we were furnished with a more plentiful portion of rice and limited supply of water. That night we were herded into ranks and marched to another point several kilometers away and placed on the sands of a beach. We waited there all that following day and night in the hot sun while horses were being unloaded from some Japanese ships. The next day, men and officers dying from the usual causes (dysentery mostly) were loaded into the forward and after holds of these cattle carriers for the second leg of a trip (beyond the belief of people in our so-called civilized age).[59]

The survivors of the Oryoku Maru boarded the Enoura Maru on “the 28th or 29th of December and the Japanese again started for Japan. No words can adequately describe the horrible sufferings endured on this second hell-ship.”[60] As Weller explained, the “violent rages, the blood-suckings and murders of the Manila-Olongapo trip were no longer possible. The men were too weak. They were broken or at least submissive. For them it was no longer their affair; they belonged to God or fate.”[61] Theodore explained what happened to the Enoura Maru:

On the 14th of January, 1945, the Americans bombed us off Takao, Formosa. Some five hundred or so were instantly killed in the forward hold (mostly all officers) and some three hundred and twenty-some odd injured or killed in the after hold. From that ship we were transferred to another pile of junk and thus started a freezing trip to Southern Japan… to Moji … to be exact.[62]

The Allied POWs captured in the fall of the Philippines, who remained in the camps of those tropical islands, had until this point lived in relatively warm climates. Virtually none were prepared for winter in Japan. The prisoners who escaped the Enoura Maru sailed the final leg of their death cruise from Formosa to Japan onboard the hell ship Brazil Maru. Sudden exposure to the cold soon compounded all of their problems. As written by Weller:

The search for water was as remorseless as if they were in the Sahara. “I remember a morning four days out of Japan when someone peeked over the ladder and saw there was sleet and snow remaining on deck,” says Chief Yeoman Theodore R. Brownell of Fort Smith, Arkansas. “I sneaked up the ladder, crept on deck and saw the most beautiful thing in the world―a long, thick icicle. But just as I reached for it the Jap sentry saw me. ‘Kudai!’ (Look out!) he yelled, and came for me with his bayonet. I had scooped up a snowball to make sure I had something even if I missed out on the icicle. But in scrambling out of the way of his bayonet I lost even the snowball and fell back into the hold again, empty-handed and thirsty as ever.”

The Navy chief, slender and medium-sized, had found a comrade in a long Army beanpole, Private William Earl Surber of Colorado Springs. “We lay together like a tablespoon and a teaspoon,” says Brownell. “But I got the best of it. He was long enough to keep me warm, but I wasn’t long enough to keep him warm at the ends.” Surber, the more ill of the pair, had alternating periods of delirium and normalcy. In normalcy he talked about wanting two things: to eat one more dish of meatballs and spaghetti, and to have a regular baptism. The men talked often of the hereafter which they both expected to enter shortly, and repeatedly Surber said, “I’m worried. I want to get baptized.” Brownell, a Catholic, thought it proper that Surber, a Protestant, should be baptized by a Protestant rite. By now the prison ship was in Japanese waters and not a single chaplain still alive was sane and strong enough to approach Surber. The chaplain Brownell counted on was Lieutenant Commander H. R. Trump, an Episcopalian who was lying a few bays off, unable to move. Since Surber could not be moved to Trump, Brownell was trying to build up the chaplain’s strength enough to walk to the soldier’s bay. The chaplain would accept food but no water from the Navy chief, and he died on the 27th. “Ted, you’ve got to get me baptized,” Surber kept saying. “I’ve got to be baptized somehow today. If there aren’t any chaplains, can’t you baptize me?”

Since any lay person can baptize another, Brownell could not refuse. But he had no water, not even a tablespoonful. “I didn’t see any way out,” says Brownell. “So I did something that I guess any clergyman would think pretty awful. I baptized Earl with my own saliva. I simply put my fingers in my mouth, got enough moisture on them so he could feel it, and I said, ‘I baptize thee in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost.’”

Surber’s expression became more peaceful. Before first light on the morning of the 28th, about 4 a.m., Brownell noticed that his friend’s body had grown cold.

They saw and smelled Japan on the 30th. The bays by now had much more room. In Brownell’s, for example, four out of nine had died; this proportion was about representative, though some bays were better, some worse. On the last night, off the entrance to Moji, there was a submarine attack, with American torpedoes blasting the night with flame as they struck the shore. But finally they were in the harbor of Moji in northern Kyushu, and the net closed behind them.[63]

It was mid-winter, the temperature just above freezing. The Japanese lined the prisoners up on the deck and ordered them to strip naked. They were then sprayed with disinfectant from blowguns―hair, face, beard and then the whole shivering body. Many prisoners were in pneumonia’s first stages already.

The last muster aboard the ship was called. It showed 435 men still alive (a few survivors say 425). Many were sinking and beyond recall. But the last voyage by sea had ended with about one-half the men living who survived the Formosan bombing, or a little more than one-fourth of the 1,600 men who left Bilibid prison on December 13th.[64]

The Navy chief, slender and medium-sized, had found a comrade in a long Army beanpole, Private William Earl Surber of Colorado Springs. “We lay together like a tablespoon and a teaspoon,” says Brownell. “But I got the best of it. He was long enough to keep me warm, but I wasn’t long enough to keep him warm at the ends.” Surber, the more ill of the pair, had alternating periods of delirium and normalcy. In normalcy he talked about wanting two things: to eat one more dish of meatballs and spaghetti, and to have a regular baptism. The men talked often of the hereafter which they both expected to enter shortly, and repeatedly Surber said, “I’m worried. I want to get baptized.” Brownell, a Catholic, thought it proper that Surber, a Protestant, should be baptized by a Protestant rite. By now the prison ship was in Japanese waters and not a single chaplain still alive was sane and strong enough to approach Surber. The chaplain Brownell counted on was Lieutenant Commander H. R. Trump, an Episcopalian who was lying a few bays off, unable to move. Since Surber could not be moved to Trump, Brownell was trying to build up the chaplain’s strength enough to walk to the soldier’s bay. The chaplain would accept food but no water from the Navy chief, and he died on the 27th. “Ted, you’ve got to get me baptized,” Surber kept saying. “I’ve got to be baptized somehow today. If there aren’t any chaplains, can’t you baptize me?”

Since any lay person can baptize another, Brownell could not refuse. But he had no water, not even a tablespoonful. “I didn’t see any way out,” says Brownell. “So I did something that I guess any clergyman would think pretty awful. I baptized Earl with my own saliva. I simply put my fingers in my mouth, got enough moisture on them so he could feel it, and I said, ‘I baptize thee in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost.’”

Surber’s expression became more peaceful. Before first light on the morning of the 28th, about 4 a.m., Brownell noticed that his friend’s body had grown cold.

They saw and smelled Japan on the 30th. The bays by now had much more room. In Brownell’s, for example, four out of nine had died; this proportion was about representative, though some bays were better, some worse. On the last night, off the entrance to Moji, there was a submarine attack, with American torpedoes blasting the night with flame as they struck the shore. But finally they were in the harbor of Moji in northern Kyushu, and the net closed behind them.[63]

It was mid-winter, the temperature just above freezing. The Japanese lined the prisoners up on the deck and ordered them to strip naked. They were then sprayed with disinfectant from blowguns―hair, face, beard and then the whole shivering body. Many prisoners were in pneumonia’s first stages already.

The last muster aboard the ship was called. It showed 435 men still alive (a few survivors say 425). Many were sinking and beyond recall. But the last voyage by sea had ended with about one-half the men living who survived the Formosan bombing, or a little more than one-fourth of the 1,600 men who left Bilibid prison on December 13th.[64]

The Brazil Maru arrived in Moji-ku, a ward of the city Kitakyuhsu, in the Fukuoka Prefecture, on the Japanese home island of Kyushu. Another hundred prisoners died as a direct result of the death cruise, immediately after they were brought ashore. Theodore spent the remainder of the war at the Fukuoka POW Camps #1 and #17, where prisoners toiled for the emperor as slaves in Japan’s largest coal mine, the Mitsui-Miike.

The Allied POWs around Fukuoka watched the mushroom cloud go up over the Kyushu city of Nagasaki on August 9. The atomic bombing of Nagasaki compelled the Emperor of Japan to surrender unconditionally. From Fukouka the POWs traveled to the ruins of Nagasaki, where they met Weller, who interviewed them extensively before they departed Japan. In a list of “characteristic statements from those who saw the atomic bomb explode thirty miles away in Nagasaki,” Weller quoted Theodore: “The best words I’ve heard in Japanese were two officials on a telephone, saying, ‘B-29s and many, many dead.’”[65]

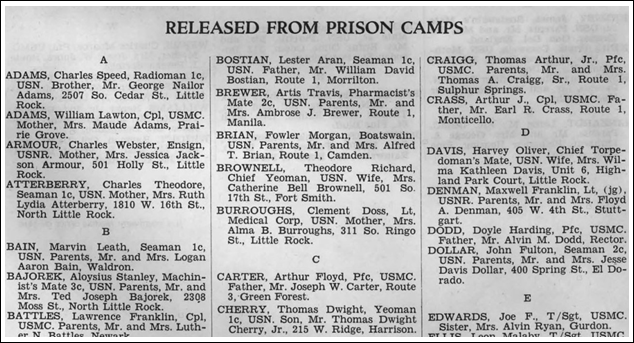

Arkansas Combat Connected Naval Casualties of World War II.[66]

The official report of Theodore’s liberation is dated October 15, 1945. The news reached Fort Smith two days later, on the birthday of Theodore’s son Richard, who got “the best gift one could ask for: His father was coming home.” Richard later recalled “going out to meet his father, who was being driven in his grandfather’s Model 8 Ford.” After the two hugged, Richard said his father “pushed me away and said ‘Happy birthday, son.’ That was pretty cool for me.”[67] Theodore returned home a decorated war hero, and retired in California. The Navy recalled him for another four years of service during the Korean War. Although Theodore did not deploy, he played a vital role in the war effort, as a recruiter. Richard, who enlisted in the Navy at the age of seventeen in April of 1948, did deploy to Korea. Richard also served in Vietnam with the Seabees.

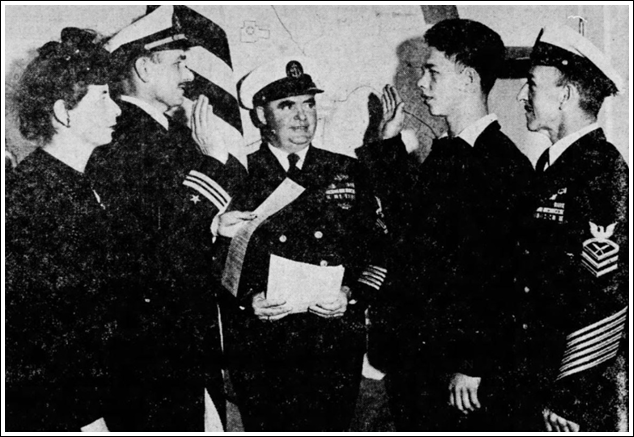

Catherine Murrey Brownell, Lieutenant Commander DeForest Hamilton, Chief Motor Machinist Mate George Corbin, Richard Brownell, and Chief Yeoman Theodore Brownell.[68]

The Brownells did not descend from a dynasty of Sailors, but Theodore certainly founded one of his own. Through the career of his son, Senior Chief Yeoman Richard Murrey Brownell, and through the career of Richard’s son, Commander Theodore Richard Brownell II, the Brownell family Navy dynasty stood for “over 95 years of unbroken service.”[69]

Theodore and Richard, as Chiefs Yeoman.[70]

As an administrator, a minister, an entertainer, a senior enlisted leader, a Canopus Sailor, and a Corregidor Marine, Chief Yeoman Theodore Brownell of Fort Smith, Arkansas, did a yeoman’s job in World War II. While forced to endure starvation, dehydration, exposure, slave labor, death marches, and hell ships, firsthand accounts consistently describe him as a man unbroken, always helpful and resourceful, who never lost his sense of humor, and possessed “wisdom far in excess of his rank.”[71] Although the graves of his parents in Calvary Cemetery are all that remains of the Brownell family in Fort Smith, the people of their hometown will always remember Theodore’s service and sacrifice, woven into some of the most epic last stand and survival tales in American military history.

| * * * |

Show Notes

Endnotes

[1]. “US Navy Chief Petty Officer Rating Badge with Specialty – E7: YN – Yeoman – Male – Vanchief – Gold on Blue,“ Milford Army Navy, accessed 8 October 2021, https://www.milfordarmynavy.com/product_p/7387610.htm.

[2]. “Yeoman’s/yeoman work/service,” Merriam-Webster , accessed 8 October 2021, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/yeoman’s/yeoman%20work/service.

[3]. “Yeoman,” Merriam-Webster, accessed 8 October 2021, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/yeoman.

[4]. “A Brief List of Old, Obscure, and Obsolete U.S. Navy Jobs” US Naval Institute, 5 September 2016, https://news.usni.org/2014/12/03/brief-list-old-obscure-obsolete-u-s-navy-jobs.

[5]. “Everything’s Relative in the Navy,” All Hands number 600 (January 1967), 22.

[6]. “People Pages,” Campus Volume VII, Number 11 (November 1978), 32.

[7]. Tom Wing, “Witness at the End, the Boston Store,” Do South Magazine, 31 July 2018, https://dosouthmagazine.com/witness-at-the-end-the-boston-store/.

[8]. “U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995,“ indexed database and digital images, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com, accessed 8 October 2021), image 52, Theodore Brownell entry, citing Fort Smith, Arkansas City Directory, 1928 (Fort Smith: Calvert-McBride Printing Company, 1928).

[9]. Gene Zaleski, “Stories of Honor: Navy Veteran Served in 2 Wars: Brownell Followed in His Father’s Footsteps,” The Times and Democrat , 22 June 2019, https://thetandd.com/news/local/stories-of-honor-navy-veteran-served-in-2-wars-brownell-followed-in-his-fathers-footsteps/article_9b02b468-1681-5d85-86c9-f8e9c5b621c6.html.

[10]. J. Michael Miller, From Shanghai to Corregidor: Marines in Defense of the Philippines (Washington, DC: United States Marine Corps History and Museums Division, 1997), 3.

[11]. Ibid., 1.

[12]. Ibid., 6.

[13]. “Vaga I (YT-116),” Navy History and Heritage Command, 20 October 2015, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/v/vaga-i.html.

[14]. George Weller, “Hell-Ship Japs Denied Yanks Water Even for Baptisms for the Dying, but Sold Driblets for Wedding Rings,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, 19 November 1945, 19.

[15]. Walter Cronkite, foreword of First Into Nagasaki: The Censored Eyewitness Dispatches on Post-Atomic Japan and Its Prisoners of War by George Weller, edited by Anthony Weller (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2006), ix.

[16]. Michael Norman, “Bataan Death March,” Brittanica, accessed 8 October 2021, https://www.britannica.com/event/Bataan-Death-March.

[17]. “Theodore Brownell", The Hall of Valor Project, accessed 8 October 2021, https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/301617.

[18]. “Navy Is Now Father and Son Affair,” Santa Rosa Republican, 07 Apr 1948, 14.

[19]. “80-G-1014615 USS Canopus,” Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed 8 October 2021, https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nara-series/80-g/80-G-1010000/80-G-1014615.html.

[20]. “Canopus,” Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed 8 October 2021, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/c/canopus.html.

[21]. Norman Polmar and Thomas B. Allen, World War II: The Encyclopedia of the War Years, 1941-1945 (Mineola: Dover Publications, 2012),137.

[22]. Ibid.

[23]. Eric Hammel, Pacific Warriors: The U.S. Marines in World War II, a Pictorial Tribute (St. Paul: Zenith Press, 2005), 48.

[24]. Eric Hammel, Coral and Blood (Pacifica: Pacifica Military History, 2009), 65.

[25]. Miller, From Shanghai to Corregidor, 24.

[26]. Eric Morris, Corregidor: The American Alamo of World War II (New York: Cooper Square Press, 2000), 393.

[27]. Miller, From Shanghai to Corregidor, 25.

[28]. John Vader, “Japanese Capture of the Philippines,” Last China Band, accessed 8 October 2021, http://lastchinaband.com/photos_fall.htm.

[29]. Miller, From Shanghai to Corregidor, 26.

[30]. Ibid.

[31]. Ibid., 28.

[32]. Ibid., 34.

[33]. Ibid., 36.

[34]. Ibid.

[35]. Ibid., 37.

[36]. Ibid.

[37]. Ibid., 39.

[38]. Ibid., 40.

[39]. Ibid.

[40]. Ibid.

[41]. Ibid., 41.

[42]. Theresa Kaminski, Angels of the Underground: The American Women Who Resisted the Japanese in the Philippines in WWII (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 152.

[43]. Ibid.

[44]. Ibid., 153.

[45]. Naval Education and Training Command, Captivity: The Extreme Circumstance (Pensacola: Naval Education and Training Professional Development and Technology Center, 2011), 2-21.

[46]. “Theater Players,” Mansell, accessed 8 October 2021, http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/theater_players-opmg_report.jpg.

[47]. Ibid.

[48]. “Office of the Provost Marshal General Report on American Prisoners of War Interned By the Japanese in the Philippines,” Mansell, accessed 8 October 2021, http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/pows_in_pi-OPMG_report.html.

[49]. Bob Wilbanks, Last Man Out: Glenn McDole, USMC, Survivor of the Palawan Massacre in World War II (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2004), 118.

[50]. Ibid.

[51]. Ibid., 119.

[52]. Mike Barber, “Leader of WWII’s ‘Great Raid’ Looks Back at Real-Life POW Rescue,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer Reporter, 24 August 2005, https://www.seattlepi.com/local/article/Leader-of-WWII-s-Great-Raid-looks-back-at-1181340.php.

[53]. Robert C. Daniels, “Hell Ship – From the Philippines to Japan,” Military History Online, 12 November 2011, https://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/WWII/HellShip.

[54]. Weller, First Into Nagasaki, 234.

[55]. Wyatt Olsen, “Memorial Honors POWs Who Died on Infamous Japanese ‘Hellships’ of WWII,” Stars and Stripes, 16 August 2018, https://www.stripes.com/news/memorial-honors-pows-who-died-on-infamous-japanese-hellships-of-wwii-1.542854.

[56]. John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945 (New York: Random House, 1970), 601.

[57]. George Weller, “Prisoners Little More Than Animals Fighting to Live as Ship Nears Japan,” Saint Louis Post Dispatch, 24 November 1945, 6A.

[58]. Clifford M. Drury, The History of the Chaplain Corps, United States Navy Volume Two 1939-1949 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1949), 37.

[59]. Ibid.

[60]. Ibid.

[61]. Weller, First Into Nagasaki, 231.

[62]. Drury, History of the Chaplain Corps, 37.

[63]. Weller, First Into Nagasaki, 236.

[64]. Ibid., 237.

[65]. Ibid., 89.

[66]. Combat Connected Naval Casualties World War II By States, Volume 1, Arkansas (Washington, DC: Navy Department, 1946), 25.

[67]. Zaleski, “Stories of Honor.”

[68]. Santa Rosa Republican, 14.

[69]. “Richard ‘Dick’ Murrey Brownell,” Tribute Archive, accessed 8 October 2021, https://www.tributearchive.com/obituaries/17989580/Richard-Dick-Murrey-Brownell.

[70]. All Hands, 22.

[71]. Ted Williams, Rogues of Bataan (New York: Carlton Press, 1979), 119.

| * * * |

© 2026 Chad Davis

Published online: 05/23/2022. Written by Chad Davis. If you have questions or comments on this article, please contact Chad Davis at: chadcdavis@protonmail.com.

About the author:

Chad Clifford Davis is an honorably discharged US Navy veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan with a BA in History and Political Science from the University of Arkansas at Fort Smith.

* Views expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily represent those of MilitaryHistoryOnline.com.