Cannae in Military History and Theory

By Andrew Wright

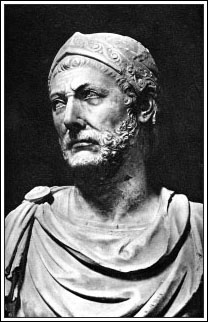

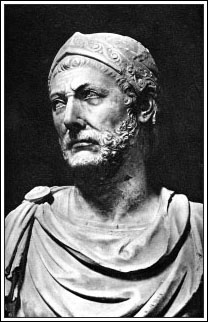

Cannae holds an unique place in military history and theory. It was arguably the most brilliant tactical victory of all time. It was also among the few cases where a significantly outnumbered opponent not only defeated, but completely annihilated, the opposing army. It was so successful that more than 2000 years later soldiers still dream about using a double encirclement to inflict an overwhelming defeat upon an enemy in battle. However, despite the undoubted tactical success Hannibal achieved against Rome at Cannae many of these same soldiers seem to have ignored other less savoury lessons from the battle. Indeed Hannibal's victory at Cannae did not lead to decisive strategic results and ultimately Carthage lost the war. Cannae's tactical results have tended to overshadow the fact that strategically it accomplished nothing significant for Carthage in the long term. The "Battle of Cannae" was a pivotal moment during the "Second Punic War" fought between Carthage and the Roman Empire to determine which power would dominate the Central and Western Mediterranean.

The Third Romano-Samnite War

By Gordon Davis

In 316 BC war broke out once again between Rome and the Samnite tribes of the central Apennines – the third such conflict between the Italian belligerents since their initial clash in 343 BC. This new conflagration was to become the longest period of sustained warfare between the two powers, eventually, during its course widening its scope of contestants to include the Sabellians of the Abruzzi and the cities of the Etruscan League. The initial five years of this new war, however, only concerned the forces of the Romans and the Samnites and it is this phase of the third war’s operations which is covered in this study. The next and final phase of this war (311 – 304 BC) will be analysed in a later document. During the fighting in these years Rome’s military endeavors gained in scope and scale, as it punched and counter-punched with its Samnite foe. The standard compliment of the army had by now very likely increased from two to four legions, as necessity demanded and as new manpower resources came online from the maturing sections of Rome’s expanding hegemony.

The Battle of Thatis River

By John Patrick Hewson

In the second half of the sixth century BC a large scale tribal movement took place north of the Black sea. This began when the Massagetai, the largest and most powerful of the tribes of north Central Asia, undertook an aggressive expansion into the steppes of Kazakhstan. During this process they either enslaved or integrated into their horde many of the nomadic horse tribes of central Asia. We know very little about the resulting confederation except that its success was due in part to the development of a new form of elite heavy cavalry known to the Greeks as Kataphraktoi, which became what we know as Cataphracts.

The Battle of Megiddo

By John Patrick Hewson

The battle of Megiddo is the earliest battle of which there is some historical record, although the record is fragmented and sketchy. And, although no complete record of the tactics exists, we do have some information at our disposal. James Henry Breasted, in his “Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents” published in Chicago in 1906, gives a translation of an inscription from the Amen temple at Karnak which gives some details of the battle. A slightly different translation is given by J. B. Pritchard in “Ancient Near Eastern Texts” published in 1969. In addition, a tentative map of the battlefield is given in “Carta’s Atlas of the Bible” by Yohanan Aharoni, published in Jerusalem in 1964.

The Third Battle of Anchialus

By John Patrick Hewson

For close to 500 years the Byzantine Empire conducted relations, sometimes as allies, sometimes at war, with the Bulgars. The Bulgars were originally a Turkic people who, like other Central Asian peoples, had a reputation as military horsemen, and they had developed a strong political organization based on the Khan as leader. The Khans came from the aristocratic class of Boyars, and were augmented by senior military commanders called Tarkhans. In the second century, the Bulgars migrated to an area between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, and sometime between 351 and 377, a group of them crossed the Caucasus to settle in Armenia.

The Second Samnite War

By Gordon Davis

Between 343 BC and 290 BC the Romans and Samnites engaged in a series of fierce wars throughout central Italy. The two peoples, along with the Celts of the Po Valley to the north, were ascendant powers at this time, eclipsing older power blocks such as Hellas Megale and the Etruscan city-states. The fighting of 327 – 321 BC between Rome and Samnium was the opening phase of the second war between these two states and it was far more intense in both the breadth of territory covered and the number of battles fought than the first war of 343 – 341 BC. The present article attempts to provide a detailed military history of the fighting of this seven-year period.

War and Conquest in Southern Italy (342-327)

By Gordon Davis

Livy indicates that the consuls eventually decided to try to break out through either of the two forks, instead of moving deeper into the hill-country of central Samnium to the east. The legions issued from the camp, formed up and advanced their standards against the Samnite fortifications. In undoubtedly some hard and desperate fighting, they were nowhere successful. Each assault, however determined and ferocious, was bloodily repulsed. Fighting through a fortified defile is an incredibly difficult endeavour, as the Persians had found out at Thermopylae in 480 BC.

Brasidas - Sparta's Most Extraordinary Commander

By Jon Martin

During the opening phase of the Peloponnesian War (431-422 BC), Sparta produced a commander that would shape the tactics, strategy and personal conduct of military leaders to follow. Both Xenophon and Alexander the Great must have studied his campaigns, for his signature is indelibly marked on their exploits. Although Lysander is the best known of the Spartan commanders of the war, being the architect of final victory, no other single Spartan exhibited the flexibility of intellect, persuasiveness of oratory and bravery and skill in combat. So exceptional were his abilities that traditional, ultra-conservative Sparta did as much to suppress his actions as did any Athenian foe. In a more modern context, he may be compared to Rommel, a popular and chivalric general, dispatched by his country to a remote theater of war, with an inadequate force and little expectation of success. Like Rommel, he would astonish enemy and friend with his victories, but unlike Rommel, he would ultimately triumph.

The Battle of Kadesh

By Rob Wanner

The Battle of Kadesh is truly the mother of all battles, in every sense. Fought on the banks of the Orontes River in Syria, this is the earliest battle of which true military tactics are known. Pharoah Ramesses II led an army of 20,000 men in an attempt to maintain his crumbling empire. Muwatallish, the Hittite king, had set an ambush for the Egyptians, sending about 1,500 chariots, each holding three men. Muwatallish had sent the force to test the strength of the armies of Egypt. The Egyptian Re Division was surprised by a small Hittite chariot force that had just forded the Orontes River. The chariot force chased after the scattered Re Division, straight into the Amun military camp. This Hittite force now had a chance to destroy Ramesses II himself. A distressed Re Division dashed into the Amun camp and created confusion among their fellow soldiers. The Hittites followed closely behind and surrounded the camp. They closed the circle inward, dispelling the unprepared soldiers from the tents. Ramesses II watched his plans to control his Kadesh fall apart around him as his enemies closed in. How did it come down to this?

King Arthur

By Steve Haas

In order to understand Arthur, you have to have a little time-sense. Rome was in the process of decay; Rome fell to Alaric, the Hun in 403, A.D., and this marked the effective end of the Eastern Roman Empire, though it continued on in various forms for a few years after. The story of Arthur is also the story of the fall of the Roman Empire. I shall give a brief history of THAT as it relates to Britain (don't worry, I'm not doing a Gibbons here, re-writing 'The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.' Just insofar as Britain is concerned). Arthur lived in the period of 460 to about 540 A.D., so you can see, from these dates, what was happening in Britain; they couldn’t depend on Rome anymore, and were on their own, so to speak. Most of this story has to deal with the decline of Roman power in Britain, and the attempts by the British to defend themselves without the Imperial Legion.

Thermopylae

By J.D. Miller

A complete chronicle of the battle of Thermopylae is impossible because the only survivors on the Allied side were the surrendered Thebans. It was possible that Herodotus, the father of history, used the accounts of these Thebans for his flawed history of the battle. Although some historians sympathize with Herodotus, they do not completely agree with him nor take his word as complete fact. For example, historian Arther Ferrill comments that "[Herodotus’] sources were the men on the street. These two factors – inexperience and lack of really good sources - excuse Herodotus as far as most scholars are concerned for his "ignorance" of strategy and tactics and blunders in his narrative of military action" (Ferrill 103).

The Roman Invasion of Anglesey

By John Griffiths

Some military historians have argued that the murderous attack on Anglesey in AD60 could be likened to butchery whilst history itself records that the assault on the island was particularly vicious, with little quarter given. It has been said to have been one of the bloodiest campaigns undertaken by the Romans in Britain, acknowledging that the purpose of the campaign and its leader - Suetonius Paullinus - were both well matched. In reality there were only ever two ways in which to bring other civilisations under the pax Romana; assimilation within the Roman way – or annihilation. History shows that Roman achievements were won ruthlessly, even to the extent of destroying whole civilisations in the process. Within the oft recalled expression concerning the glories of Rome one must not forget that this same achievement was often won by the Empire flexing its considerable muscle.

The Fall of the Roman Empire

By Addison Hart

Early in the first century BC, a Roman teenager from a minor patrician family visited Nicomedes, King of Bithynia. On his return trip to the city of Rome, the historian Plutarch tells us that “he was captured by pirates near the island of Pharmacusa. At that time there were large fleets of pirates, with ships large and small, infesting the seas everywhere.” When the boy was first captured, the pirates demanded that the family pay twenty gold talents for his safe return, but it was soon upped to a good fifty talents when the boy told them that they did not understand the importance of their new prisoner. The boy sent most of his companions away to earn the money, and he was left alone with the pirates. The boy was not at all intimidated by the villainous pirates, and for thirty-eight days he lived with them, and they grew to respect the boy, and they even began to grow a sort of bond with him. The boy once, in a jovial manner, said to them that he would one day have them crucified. They laughed with him then.

Agricola and the Final Invasion of Anglesey

By John Griffiths

Gnaeus Julius Agricola is far better known in the history of Anglesey than his predecessor, Suetonius Paulinus. Whilst Paulinus’s invasion was the first aimed at the Druidic homeland of Mona Insulis, scant knowledge is available to historians as to its extent and effect. Many historians have suggested its purpose was the total destruction of the Druids whilst others have said that the push was a determined effort to crush, totally, the base of resistance for the Ordovices of North Wales. If anything, it is generally agreed that it was left as unfinished business although the reasons for this are tactical, given the uprising which Paulinus was hastily called away to quell. The records pertaining to the second campaign under Agricola provide more detail - due, it has to be said, because the famous Roman historian Tacitus was Agricola’s son in law. Tacitus left behind a very detailed biography of his father in law thus guaranteeing him a permanent place in history as a result. Interestingly, Agricola had served under Paulinus as a military tribune during much of the British campaign.

By Andrew Wright

Cannae holds an unique place in military history and theory. It was arguably the most brilliant tactical victory of all time. It was also among the few cases where a significantly outnumbered opponent not only defeated, but completely annihilated, the opposing army. It was so successful that more than 2000 years later soldiers still dream about using a double encirclement to inflict an overwhelming defeat upon an enemy in battle. However, despite the undoubted tactical success Hannibal achieved against Rome at Cannae many of these same soldiers seem to have ignored other less savoury lessons from the battle. Indeed Hannibal's victory at Cannae did not lead to decisive strategic results and ultimately Carthage lost the war. Cannae's tactical results have tended to overshadow the fact that strategically it accomplished nothing significant for Carthage in the long term. The "Battle of Cannae" was a pivotal moment during the "Second Punic War" fought between Carthage and the Roman Empire to determine which power would dominate the Central and Western Mediterranean.

The Third Romano-Samnite War

By Gordon Davis

In 316 BC war broke out once again between Rome and the Samnite tribes of the central Apennines – the third such conflict between the Italian belligerents since their initial clash in 343 BC. This new conflagration was to become the longest period of sustained warfare between the two powers, eventually, during its course widening its scope of contestants to include the Sabellians of the Abruzzi and the cities of the Etruscan League. The initial five years of this new war, however, only concerned the forces of the Romans and the Samnites and it is this phase of the third war’s operations which is covered in this study. The next and final phase of this war (311 – 304 BC) will be analysed in a later document. During the fighting in these years Rome’s military endeavors gained in scope and scale, as it punched and counter-punched with its Samnite foe. The standard compliment of the army had by now very likely increased from two to four legions, as necessity demanded and as new manpower resources came online from the maturing sections of Rome’s expanding hegemony.

The Battle of Thatis River

By John Patrick Hewson

In the second half of the sixth century BC a large scale tribal movement took place north of the Black sea. This began when the Massagetai, the largest and most powerful of the tribes of north Central Asia, undertook an aggressive expansion into the steppes of Kazakhstan. During this process they either enslaved or integrated into their horde many of the nomadic horse tribes of central Asia. We know very little about the resulting confederation except that its success was due in part to the development of a new form of elite heavy cavalry known to the Greeks as Kataphraktoi, which became what we know as Cataphracts.

The Battle of Megiddo

By John Patrick Hewson

The battle of Megiddo is the earliest battle of which there is some historical record, although the record is fragmented and sketchy. And, although no complete record of the tactics exists, we do have some information at our disposal. James Henry Breasted, in his “Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents” published in Chicago in 1906, gives a translation of an inscription from the Amen temple at Karnak which gives some details of the battle. A slightly different translation is given by J. B. Pritchard in “Ancient Near Eastern Texts” published in 1969. In addition, a tentative map of the battlefield is given in “Carta’s Atlas of the Bible” by Yohanan Aharoni, published in Jerusalem in 1964.

The Third Battle of Anchialus

By John Patrick Hewson

For close to 500 years the Byzantine Empire conducted relations, sometimes as allies, sometimes at war, with the Bulgars. The Bulgars were originally a Turkic people who, like other Central Asian peoples, had a reputation as military horsemen, and they had developed a strong political organization based on the Khan as leader. The Khans came from the aristocratic class of Boyars, and were augmented by senior military commanders called Tarkhans. In the second century, the Bulgars migrated to an area between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, and sometime between 351 and 377, a group of them crossed the Caucasus to settle in Armenia.

The Second Samnite War

By Gordon Davis

Between 343 BC and 290 BC the Romans and Samnites engaged in a series of fierce wars throughout central Italy. The two peoples, along with the Celts of the Po Valley to the north, were ascendant powers at this time, eclipsing older power blocks such as Hellas Megale and the Etruscan city-states. The fighting of 327 – 321 BC between Rome and Samnium was the opening phase of the second war between these two states and it was far more intense in both the breadth of territory covered and the number of battles fought than the first war of 343 – 341 BC. The present article attempts to provide a detailed military history of the fighting of this seven-year period.

War and Conquest in Southern Italy (342-327)

By Gordon Davis

Livy indicates that the consuls eventually decided to try to break out through either of the two forks, instead of moving deeper into the hill-country of central Samnium to the east. The legions issued from the camp, formed up and advanced their standards against the Samnite fortifications. In undoubtedly some hard and desperate fighting, they were nowhere successful. Each assault, however determined and ferocious, was bloodily repulsed. Fighting through a fortified defile is an incredibly difficult endeavour, as the Persians had found out at Thermopylae in 480 BC.

Brasidas - Sparta's Most Extraordinary Commander

By Jon Martin

During the opening phase of the Peloponnesian War (431-422 BC), Sparta produced a commander that would shape the tactics, strategy and personal conduct of military leaders to follow. Both Xenophon and Alexander the Great must have studied his campaigns, for his signature is indelibly marked on their exploits. Although Lysander is the best known of the Spartan commanders of the war, being the architect of final victory, no other single Spartan exhibited the flexibility of intellect, persuasiveness of oratory and bravery and skill in combat. So exceptional were his abilities that traditional, ultra-conservative Sparta did as much to suppress his actions as did any Athenian foe. In a more modern context, he may be compared to Rommel, a popular and chivalric general, dispatched by his country to a remote theater of war, with an inadequate force and little expectation of success. Like Rommel, he would astonish enemy and friend with his victories, but unlike Rommel, he would ultimately triumph.

The Battle of Kadesh

By Rob Wanner

The Battle of Kadesh is truly the mother of all battles, in every sense. Fought on the banks of the Orontes River in Syria, this is the earliest battle of which true military tactics are known. Pharoah Ramesses II led an army of 20,000 men in an attempt to maintain his crumbling empire. Muwatallish, the Hittite king, had set an ambush for the Egyptians, sending about 1,500 chariots, each holding three men. Muwatallish had sent the force to test the strength of the armies of Egypt. The Egyptian Re Division was surprised by a small Hittite chariot force that had just forded the Orontes River. The chariot force chased after the scattered Re Division, straight into the Amun military camp. This Hittite force now had a chance to destroy Ramesses II himself. A distressed Re Division dashed into the Amun camp and created confusion among their fellow soldiers. The Hittites followed closely behind and surrounded the camp. They closed the circle inward, dispelling the unprepared soldiers from the tents. Ramesses II watched his plans to control his Kadesh fall apart around him as his enemies closed in. How did it come down to this?

King Arthur

By Steve Haas

In order to understand Arthur, you have to have a little time-sense. Rome was in the process of decay; Rome fell to Alaric, the Hun in 403, A.D., and this marked the effective end of the Eastern Roman Empire, though it continued on in various forms for a few years after. The story of Arthur is also the story of the fall of the Roman Empire. I shall give a brief history of THAT as it relates to Britain (don't worry, I'm not doing a Gibbons here, re-writing 'The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.' Just insofar as Britain is concerned). Arthur lived in the period of 460 to about 540 A.D., so you can see, from these dates, what was happening in Britain; they couldn’t depend on Rome anymore, and were on their own, so to speak. Most of this story has to deal with the decline of Roman power in Britain, and the attempts by the British to defend themselves without the Imperial Legion.

Thermopylae

By J.D. Miller

A complete chronicle of the battle of Thermopylae is impossible because the only survivors on the Allied side were the surrendered Thebans. It was possible that Herodotus, the father of history, used the accounts of these Thebans for his flawed history of the battle. Although some historians sympathize with Herodotus, they do not completely agree with him nor take his word as complete fact. For example, historian Arther Ferrill comments that "[Herodotus’] sources were the men on the street. These two factors – inexperience and lack of really good sources - excuse Herodotus as far as most scholars are concerned for his "ignorance" of strategy and tactics and blunders in his narrative of military action" (Ferrill 103).

The Roman Invasion of Anglesey

By John Griffiths

Some military historians have argued that the murderous attack on Anglesey in AD60 could be likened to butchery whilst history itself records that the assault on the island was particularly vicious, with little quarter given. It has been said to have been one of the bloodiest campaigns undertaken by the Romans in Britain, acknowledging that the purpose of the campaign and its leader - Suetonius Paullinus - were both well matched. In reality there were only ever two ways in which to bring other civilisations under the pax Romana; assimilation within the Roman way – or annihilation. History shows that Roman achievements were won ruthlessly, even to the extent of destroying whole civilisations in the process. Within the oft recalled expression concerning the glories of Rome one must not forget that this same achievement was often won by the Empire flexing its considerable muscle.

The Fall of the Roman Empire

By Addison Hart

Early in the first century BC, a Roman teenager from a minor patrician family visited Nicomedes, King of Bithynia. On his return trip to the city of Rome, the historian Plutarch tells us that “he was captured by pirates near the island of Pharmacusa. At that time there were large fleets of pirates, with ships large and small, infesting the seas everywhere.” When the boy was first captured, the pirates demanded that the family pay twenty gold talents for his safe return, but it was soon upped to a good fifty talents when the boy told them that they did not understand the importance of their new prisoner. The boy sent most of his companions away to earn the money, and he was left alone with the pirates. The boy was not at all intimidated by the villainous pirates, and for thirty-eight days he lived with them, and they grew to respect the boy, and they even began to grow a sort of bond with him. The boy once, in a jovial manner, said to them that he would one day have them crucified. They laughed with him then.

Agricola and the Final Invasion of Anglesey

By John Griffiths

Gnaeus Julius Agricola is far better known in the history of Anglesey than his predecessor, Suetonius Paulinus. Whilst Paulinus’s invasion was the first aimed at the Druidic homeland of Mona Insulis, scant knowledge is available to historians as to its extent and effect. Many historians have suggested its purpose was the total destruction of the Druids whilst others have said that the push was a determined effort to crush, totally, the base of resistance for the Ordovices of North Wales. If anything, it is generally agreed that it was left as unfinished business although the reasons for this are tactical, given the uprising which Paulinus was hastily called away to quell. The records pertaining to the second campaign under Agricola provide more detail - due, it has to be said, because the famous Roman historian Tacitus was Agricola’s son in law. Tacitus left behind a very detailed biography of his father in law thus guaranteeing him a permanent place in history as a result. Interestingly, Agricola had served under Paulinus as a military tribune during much of the British campaign.