A Turn Too Far: Reconstructing the End of the Battle of the Java Sea

By Jeffrey R. Cox

Author’s Preface

While in modern military history there is little that can compare to the stand of the “300” Spartans (if you ignore their 1300 or so troops from other Greek allies) against the invading Xerxes and his 100,000 Achaemenid Persian troops at Thermopylae, a very good case can be made that the Java Sea Campaign in the early days of World War II in the Pacific does just that. This three-month campaign to defend Malaya (now Malaysia) and the Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia) from the Japanese with a combined force of American, British, Dutch and Australian (ABDA) forces culminated in the disastrous Battle of the Java Sea, in which organized naval resistance to the Japanese advance was swept away. While there were no dramatic speeches, no tossing of insults, no troops fighting in their underwear, no trolls, no orcs dressed as Immortals – not that there were actually trolls or orcs at the original Thermopylae – no convenient betrayal by a treacherous goat farmer, and ultimately there was not nearly the same effectiveness as Leonidas and his Lakedaemonians, there was every bit the courage in the face of hopeless odds and the determination in the face of death to do everything they could to stop or at least delay the enemy until reinforcements – this time in the form of ships and planes produced by American industrial might – could take the offensive.

The Java Sea campaign has gotten little in the way of analysis in the English-speaking press, and what coverage it has gotten has largely focused on the role of the crews of individual ships such as the US cruiser Houston, the Australian cruiser Perth and the British cruiser Exeter, particularly in their futile efforts to escape the Java Sea, James Hornfischer’s excellent book Ship of Ghosts being a case in point. This relative silence is understandable for several reasons. First of all, we lost. Unless the defeat can be used to bash the United States like Vietnam is, defeats tend to get less play in the media. Furthermore, the territory being defended was a Dutch colony, which, since the Dutch mainland was under Nazi occupation, was effectively serving as their homeland, and thus meant much more to the Dutch than the Anglos, who found the campaign small in comparison to their overall war effort in the Pacific.

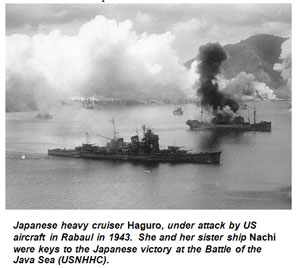

But a major reason why it has not gotten much examination is simply because of a lack of information, which is exemplified no better than in the ending of the Battle of the Java Sea. This decisive action that took over seven hours ended in what amounted to a midnight fog. The last ditch effort of the ABDA Combined Striking Force under Dutch schout-bij-nacht (rear admiral) Karel W.F.M. Doorman, now down to only four ships, was literally torpedoed by a Japanese force under Rear Admiral Takagi Takeo just before midnight on February 27, 1942. Most histories simply state that Takagi’s cruisers Nachi and Haguro torpedoed and sank the Dutch light cruisers De Ruyter and Java, while Perth and Houston sped off “into the night.” They usually say “into the night,” too.[1] That is usually where the narrative of the battle ends.

Takagi did not survive the war, losing his life on Saipan in 1944, possibly a suicide. For the Allied ships present for that late-night action, neither Karel Doorman, nor the captains of the remaining ships – Eugene E.B. Lacomblé of De Ruyter, Hector Waller of Perth, Albert Rooks of Houston and Ph.B.M. van Straelen of Java – nor their respective staffs would survive the following 26 hours.

The only reasonably contemporaneous after-action report and the best source for these last hours of the battle was filed by Captain Waller. But it was filed on February 28, 1942, as Perth was moored up with Houston in Tanjoeng Priok (now Tanjung Priok), the port of Batavia (Jakarta). Waller, who due to the death of Doorman had become senior officer of the Combined Striking Force and was thus commanding both Perth and Houston, had much more pressing responsibilities such as trying to get provisions, ammunition and fuel, and planning their escape through the Soenda (Sunda) Strait. With all this going on, it is quite understandable that Waller’s report on the battle was necessarily rushed and incomplete.[2] Consequently, though it is the best source for the end of the battle, the report is in many instances missing information, vague and subject to varying interpretations.

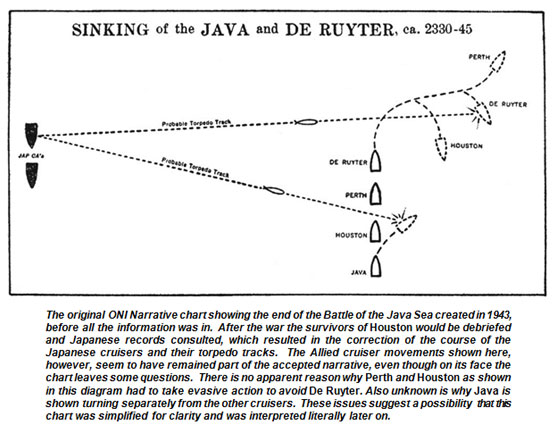

The US Navy’s Office of Naval Intelligence (“ONI”) produced a narrative of the Java Sea Campaign in 1943 (“ONI Narrative”), but it was also missing crucial information. For instance – counterintuitively – the ONI report had better information on the conduct of the Dutch in this last phase of the battle than it did on the US forces, as US Navy personnel on De Ruyter, assigned to the Dutch flagship as communications liaison, were recovered by the US submarine S-37 the day after the battle and were subsequently debriefed, while Captain Rooks and the American crewmembers of Houston had not been fully debriefed before their ill-fated sortie into the Soenda Strait.

With so little to go on, the result has been a fuzzy narrative. When histories attempt to get into more detail about the last hours of the battle, questions, some perhaps unanswerable, emerge:

• Most of the survivors have the Allied ships operating in a column going, from front to back, De Ruyter, Perth, Houston and Java. However, the survivors of Houston, debriefed after the war, are consistent in insisting that Houston was immediately behind De Ruyter, with Perth somewhere behind Houston.[3]

• Both the Allied and Japanese columns were headed north. The Japanese cruisers both used the same firing solution for their torpedoes. But the lead Japanese cruiser, Nachi, torpedoed the last Allied cruiser, Java, while the trailing Japanese cruiser, Haguro, torpedoed the lead Allied cruiser De Ruyter.

• Some histories have Java being torpedoed before De Ruyter; others have that order reversed.

• Perth had to take evasive action to avoid colliding with the stricken De Ruyter. Houston then had to take evasive action to avoid Perth. The histories insist that Perth had to swerve to port to avoid De Ruyter, while Houston swerved to starboard to avoid De Ruyter. Yet Houston had to swerve to port to avoid Perth. This set of maneuvers is contradictory and simply does not make sense.

What I have tried to do here is reconstruct these last hours of the Battle of the Java Sea, attempting to accommodate the differing and sometimes contradictory testimonials while answering or at least addressing these lingering questions. What follows is that version of events. I am putting this out there for comment and critique. I will try to identify all the source material I can to facilitate review and see where this theory withstands scrutiny and where it may not.

This reconstruction has gone through numerous rewrites, in an effort to both present a coherent, readable story and the underlying factual support within that narrative. In the end, it became apparent that such an arrangement was too awkward and unreadable. For that reason, only the reconstruction itself is presented here in, not surprisingly, narrative form for readability purposes. The supporting evidence, or statement as to a lack thereof, is presented as endnotes. Anyone reading the narrative is encouraged to read the endnotes to determine if they agree with the conclusions.

Wherever possible, the reconstruction is based original source materials like:

• Waller’s report[4];

• the ONI Narrative;

• The Fleet the Gods Forgot and The Ghost That Died at Sunda Strait, both by Walter Winslow, a survivor of Houston;

• survivors of Houston quoted in Duane Schultz’s Last Battle Station;

• survivors of De Ruyter and Java quoted in J. Daniel Mullin’s Another Six Hundred and A. Kroese’s The Dutch Navy at War.

Apparent holes are filled in with strong secondary sources such as:

• Samuel Eliot Morrison’s History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 3: The Rising Sun in the Pacific (based on US Navy records);

• Hara Tameichi’s Japanese Destroyer Captain (commanded the Japanese destroyer Amatsukaze during the battle);

• Paul Dull’s A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1941-1945) (ranking Western review of original Japanese navy records);

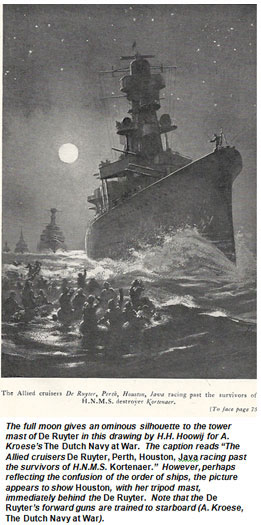

• A. Kroese’s The Dutch Navy at War (commanded the Hr. Ms. Kortenaer during the battle, and was one of the last to see the four cruisers of the Combined Striking Force pass for the last time on their way to destiny);

• F.C. van Oosten’s Battle of the Java Sea and the Dr. Ph.M. Bosscher’s De Koninklijke Marine in de Tweede Wereldoorlog (both review original Dutch sources; van Oosten also reviewed Japanese sources);

• Tom Womack’s The Dutch Naval Air Force Against Japan: The Defense of the Netherlands East Indies, 1941-1942 (reviewed original Dutch naval air force and some navy records);

• John Prados’ Combined Fleet Decoded (reviewed Japanese communications in the context of the Pacific War);

• Lodwick H. Alford's Playing for Time: War on an Asiatic Fleet Destroyer;

• J. Daniel Mullin’s Another Six Hundred; and

• Australia in the War of 1939-1945, Series Two: Navy; Volume I: Royal Australian Navy 1939-1942, by G. Hermon Gill.

Also of note are websites such as:

• Hyperwar: World War II on the Worldwide Web (where the ONI Narrative and other documents are available): http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/

• The Imperial Japanese Navy Page (tabular records of movement and design specs for IJN ships): www.CombinedFleet.com

• Royal Netherlands Navy Ships in World War II (histories, design specs and damage for De Ruyter and Java): http://www.netherlandsnavy.nl/

• The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941-42 (currently offline);

• US Asiatic Feet site (with a thorough narrative of the Java Sea campaign, “Naval Alamo” by Anthony P. Tully): http://www.asiaticfleet.com/;

• The Australian War Memorial (“AWM”): http://www.awm.gov.au/; and

• The US Naval History and Heritage Command (“USNHHC;” formerly US Naval Historical Center): http://www.history.navy.mil/index.html.

In reading this the reader will see a lot of words of ambiguity such as “probably,” “likely,” “seemingly” and “apparently.” This is because the answers to certain questions are unknown and perhaps unknowable, but such holes can perhaps be filled with deduction or at least informed speculation. Others might be filled with records which I have not yet been able to access (such as most Japanese records). Such holes can perhaps have more than one filling, and I am interested in hearing what those other possibilities might be.

So, with those disclaimers aside, please sit back, relax and enjoy the following piece of detective work about the end of the Battle of the Java Sea.

Background

In a supreme bit of irony, the Japanese had started World War II in the Pacific by attacking Pearl Harbor thousands of miles away in order to end their war in next-door China. Their objective was to secure the so-called “Southern Resources Area” – the Netherlands East Indies, now called Indonesia – to obtain the natural resources they needed to not so much win the war in China but to end that war while saving “face.” By the end of February 1942, the Japanese were on the verge of seizing the Netherlands East Indies, with only the island of Java, the most populous island of the Indies and its commercial and political center, remaining to be conquered – and Java was cut off and ready to fall.

The Allies – the United States, Britain and the Netherlands – had always believed that defense of the Far East against the Japanese was an iffy proposition at best, but the speed of the Japanese advance was still surprising. An attempt was made to pool their slender resources available into an organization called ABDACOM – the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command. The naval component – comprised of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, elements of the British Far Eastern Fleet, the Dutch East Indies Squadron and elements of the Royal Australian Navy operating under Royal Navy command – was known as ABDA-Float, which by mid-February 1942 was commanded by Dutch Admiral Conrad E. L. Helfrich.

A fully-integrated multinational force, like ABDACOM was then and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization is today, was a relatively new-fangled thing. From its inception, ABDA-Float was crippled by three major issues:

1. Communications – Integrating sailors from four different countries and three different navies who spoke two different languages was never going to be easy. The additional pressures of a fast and relentless Japanese advance made it next to impossible.

2. A complete lack of air power – The loss of the US Far Eastern Air Force (caught on the ground and destroyed by the Japanese due to the incompetence of US General Douglas MacArthur) and the British Malaya air force crippled ABDA air efforts, denied ABDA-Float necessary air protection and hampered intelligence gathering.

3. Operational accidents and mechanical breakdowns – The speed of the Japanese advance and the lack of air protection denied ABDA-Float the necessary time and security for maintenance and repair of their ships and rest for the crews. Facilities for such maintenance and repair in the Indies were basically limited to the principal Dutch naval base at Soerabaja (Surabaya)[5], which became a major target for Japanese air attacks, and one floating drydock at Tjilatjap (Cilacap)[6], inconveniently located on Java’s southern coast. The results further crippled Allied efforts.[7]

These factors would show themselves again and again.

These factors would show themselves again and again.

By the end of February, ABDACOM had proven to be ineffective and was dissolved, with the remaining ABDA forces placed under Dutch command for the last ditch defense of Java. Defense was more akin to leaving one’s head in a noose, however, as by then Java had been cut off by the losses of Malaya, Singapore and Sumatra to the west, and the islands of Bali and Timor to the east.

Tactical command of the ABDA naval forces was placed in the hands of Dutch Admiral Karel Doorman. Time and again, Doorman would sortie out to challenge the Japanese advance, only to be turned back by Japanese air attacks. So often did this happen that Doorman’s courage was questioned and he was nearly relieved of duty several times.[8] After the Battle of the Java Sea, questions about his courage seemed to vanish. Not coincidentally, so did he.[9]

The Afternoon Action of the Battle of the Java Sea

By the last few days of February 1942, Java itself was now under imminent threat. It was do or die for the Allies. The remaining ABDA warships – heavy cruisers HMS Exeter and USS Houston; light cruisers Hr. Ms. De Ruyter, Hr. Ms. Java and HMAS Perth; and destroyers HMS Electra, HMS Encounter, HMS Jupiter, Hr. Ms. Kortenaer, Hr. Ms. Witte de With, USS John D. Edwards, USS Alden, USS John D. Ford and USS Paul Jones – were combined into the appropriately-named Combined Striking Force.[10] Doorman met with the ship captains on February 26 to plan their action, but with little time or intelligence information, only a limited amount of planning could be done. So desperate were the Allies that, in the event a ship was disabled or sunk, Doorman ordered that it was “to be left to the mercy of the enemy;” the few ships they had were too needed to fight to spare any for rescue missions.[11]

On February 26, two Japanese invasion convoys, with warship escort, were reportedly descending on Java, one consisting of 56 transports for the western end of the island, the other of 41 transports for the eastern end. The Combined Striking Force was sent out under Admiral Doorman, with orders from Helfrich “to continue your attacks until the enemy is destroyed,”[12] in spite of utterly inadequate intelligence, to intercept the eastern convoy. The hope was that the eastern convoy could be destroyed quickly so the Combined Striking Force could retire to Tanjoeng Priok and sortie again to destroy the western convoy. It was a desperate operational plan with little chance of success, but the Allies were long past the point of desperation.

Doorman had his force run a sweep north of Madoera island and Java during the night of the 26th and most of the 27th, found nothing, suffered yet another air attack, and radioed Helfrich that he was returning back to base on account of the exhaustion of his crews, who had apparently been constantly kept at battle stations. This prompted a rather remarkable radio exchange in which Helfrich scolded Doorman for turning back and admonished him to continue poking blindly for the convoy, and Doorman responded by telling Helfrich, obliquely and diplomatically, that if he wanted Doorman to attack the convoy then perhaps Helfrich should tell him where the convoy was.[13]

Nevertheless, Doorman continued the search, but at 12:40 pm on the 27th reported again, “Personnel have this forenoon reached the point of exhaustion;” because of the constant danger of air and surface attack, the crews has been kept at battle stations since their sortie on the 26th.[14] He decided to retire to Soerabaja and let the crews rest until he was given better information.

Typical of Dutch luck in the war, Doorman got the location of the convoy late in the afternoon of the 27th as his force entered the swept channel of the minefield between Java and Madoera, the northern route into Soerabaja’s harbor. He immediately turned around – in the middle of the minefield. In fact, he strayed out of the swept channel into the minefield itself. None of his ships hit any mines, but that luck with mines would reverse itself later on.[15] Also typical of Dutch luck, Doorman’s abrupt about face was witnessed by a Japanese float plane.

Unfortunately for the Allies, the convoy had an escort. A strong one.

Two destroyer flotillas, the 4th with 6 destroyers and the light cruiser Naka under Rear Admiral Nishimura Shoji;[16] and the 2nd with 8 destroyers under Rear Admiral Tanaka Raizo,[17] were sandwiched around two-thirds of the Japanese 5th Cruiser Division under Rear Admiral Takagi, who served as the Japanese Officer in Tactical Command for this action.

The 5th Cruiser Division (“Sentai 5”) nominally consisted of three of the four heavy cruisers of the Myoko class –

Myoko, Nachi and Haguro. But for reasons known only to the Japanese

Myoko had been detached from Sentai 5 and attached to the fourth member of the class,

Ashigara, to serve as “distant support” for the invasion, though in Japanese nomenclature “distant support” more often than not meant “just far enough away to be of no reasonable use.” The only contribution by

Ashigara and Myoko to the campaign was to chase down the crippled

Exeter and a few cohorts. It was a stupid decision, symptomatic of the arrogance, overconfidence and sloppiness that were slowly seeping into the Japanese naval war effort, to blow up in their faces four months later at the Battle of Midway. But this campaign was too far gone for it to have much of an effect at this stage.

The 5th Cruiser Division (“Sentai 5”) nominally consisted of three of the four heavy cruisers of the Myoko class –

Myoko, Nachi and Haguro. But for reasons known only to the Japanese

Myoko had been detached from Sentai 5 and attached to the fourth member of the class,

Ashigara, to serve as “distant support” for the invasion, though in Japanese nomenclature “distant support” more often than not meant “just far enough away to be of no reasonable use.” The only contribution by

Ashigara and Myoko to the campaign was to chase down the crippled

Exeter and a few cohorts. It was a stupid decision, symptomatic of the arrogance, overconfidence and sloppiness that were slowly seeping into the Japanese naval war effort, to blow up in their faces four months later at the Battle of Midway. But this campaign was too far gone for it to have much of an effect at this stage.

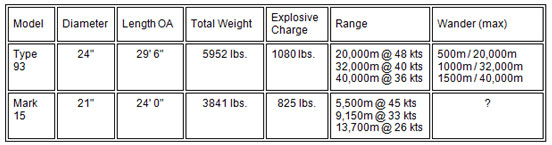

So Takagi had Nachi and Haguro, two modern cruisers who each had ten 8-inch guns and sixteen torpedo tubes (eight on each side) capable of firing the legendary Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedo.[18] Takagi also had a stable of float planes on his cruisers to monitor Doorman’s movements. Doorman did not; having expected a night action, he had left his float planes ashore in keeping with Allied doctrine which regarded float planes as fire hazards in night battles.[19 The Japanese, by contrast, were aggressive and creative with the use of their float planes throughout the war. Takagi’s float planes would prove to be a significant advantage and arguably the difference in the battle.[20]

Not that it necessarily should have been. The Allies did have their own seaplanes in the area: Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats – all three of them – from US Patrol Wing 10.[21] They did not exactly have Doorman on their speed-dial, however, as the Japanese float planes did Takagi. Patrol Wing 10’s reports had to be funneled through the communications center for the Soerabaja Naval District (“Naval Commander Soerabaja”).[22]

In contrast to the modern Nachi and Haguro and the powerful Japanese Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedo, the Allied force, though the crews were brave and well-trained, was a fairly motley collection of ships:

Exeter

– With six 8-inch guns in three dual turrets plus torpedo tubes, the British heavy cruiser Exeter was nominally the most heavily armed Allied cruiser on hand. Fresh off her famous defeat of the German “pocket battleship”

Admiral Graf Spee off the Rio de la Plata, Exeter’s crew was battle-tested as well. But the cruiser was a little aged, in desperate need of serious maintenance, and had serious and ongoing problems with her fire control (targeting) and the train (rotation) limits of her No. 3 (aft) turret.

Exeter

– With six 8-inch guns in three dual turrets plus torpedo tubes, the British heavy cruiser Exeter was nominally the most heavily armed Allied cruiser on hand. Fresh off her famous defeat of the German “pocket battleship”

Admiral Graf Spee off the Rio de la Plata, Exeter’s crew was battle-tested as well. But the cruiser was a little aged, in desperate need of serious maintenance, and had serious and ongoing problems with her fire control (targeting) and the train (rotation) limits of her No. 3 (aft) turret.

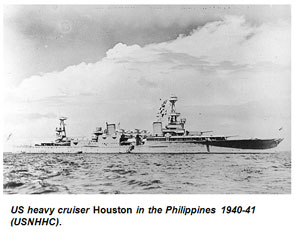

Houston – Like most US cruisers, the heavy cruiser Houston was the victim of a monumentally stupid decision by the US Navy in the 1930’s to remove the torpedo tubes from its cruisers, which left them less effective against enemy ships in general and largely defenseless against battleships in particular.[23] Houston was ostensibly the most heavily gunned Allied cruiser, with nine 8-inch guns in three triple turrets, but her No. 3 (aft) turret had been disabled by a bomb hit three weeks earlier and could not be repaired in theater.

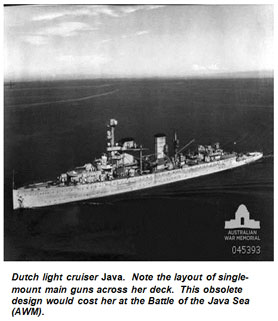

Java – Laid down in 1916, the light cruiser Java was designed to be more than a match for the Japanese cruisers of her time. Unfortunately, her time had come and gone before her completion in 1925, at which point she was already obsolete. By 1942, the light cruiser was arguably not fit for front-line service, but the Dutch were so hard-pressed for ships they had little choice.[24] Though heavily modernized with new fire control, an improved anti-aircraft package and a lot of paint,

Java still suffered from the poor watertight compartmentalization suffered by the ships of her age.[25] Additionally, while she was heavily gunned with ten 5.9-inch guns, her guns were not in armored enclosed turrets with secure access to fortified magazines, but were instead scattered in single-gun mounts across the main deck. She carried no torpedo tubes.

Java – Laid down in 1916, the light cruiser Java was designed to be more than a match for the Japanese cruisers of her time. Unfortunately, her time had come and gone before her completion in 1925, at which point she was already obsolete. By 1942, the light cruiser was arguably not fit for front-line service, but the Dutch were so hard-pressed for ships they had little choice.[24] Though heavily modernized with new fire control, an improved anti-aircraft package and a lot of paint,

Java still suffered from the poor watertight compartmentalization suffered by the ships of her age.[25] Additionally, while she was heavily gunned with ten 5.9-inch guns, her guns were not in armored enclosed turrets with secure access to fortified magazines, but were instead scattered in single-gun mounts across the main deck. She carried no torpedo tubes.

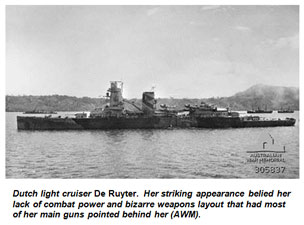

De Ruyter – With an intimidating tower mast and sleek lines, Karel Doorman’s light cruiser flagship was beautiful, but her beauty could not mask the fact that she had been built on the cheap and, consequently, was woefully underarmored and underarmed. While De Ruyter did have state-of-the-art fire control and a heavy anti-aircraft package featuring five twin-barreled Bofors 40-millimeter anti-aircraft mounts, she carried no torpedo tubes and only seven 6-inch guns. Worse, for reasons known only to the Dutch, only three of those guns faced forward, meaning that most of the cruiser’s main armament faced behind her.

Kortenaer

– Two weeks earlier, the Dutch destroyer had been slated to take part in the Allied effort to oppose the Japanese landings on Bali. However,

Kortenaer ran aground while navigating the narrow, twisting channel out of Tjilatjap and had to be left behind. The grounding caused damage to her boilers that could not be immediately repaired and limited her speed to 26 knots. By comparison, the slowest of Takagi’s ships were capable of 31 knots.

Kortenaer

– Two weeks earlier, the Dutch destroyer had been slated to take part in the Allied effort to oppose the Japanese landings on Bali. However,

Kortenaer ran aground while navigating the narrow, twisting channel out of Tjilatjap and had to be left behind. The grounding caused damage to her boilers that could not be immediately repaired and limited her speed to 26 knots. By comparison, the slowest of Takagi’s ships were capable of 31 knots.

John D. Edwards, Alden, John D. Ford, Paul Jones – the four US destroyers, grouped for this action into Destroyer Squadron 58, were from the Clemson class of “flush deckers” from the period just after World War I. The “four pipers” or “four stackers” (so called because of their four smokestacks) were underarmored and undergunned, but contained a powerful battery of 12 torpedo tubes each (six on each side), which the Allies desperately needed right now. The ships were in bad shape, in serious need of maintenance, and suffered from old machinery, leaky feed-water pipes and biofouled bottoms that limited their speeds to 26 knots.

But this was the best the ABDA navies could do. Fourteen ships – mostly old, worn and battered – from four different countries and three different navies speaking two different languages. Crews eager to dish out some of what they had been taking, but pushed beyond the point of physical and mental exhaustion. No chance to train together.[26] No chance to develop a common communications system. Not nearly enough time or intelligence information to develop anything but the most rudimentary battle plan. No accurate intelligence. No air cover whatsoever. If Doorman was to successfully carry out his orders, he would have to make it up as he went along.

The afternoon battle.

A fully detailed account of the afternoon action in the Java Sea is outside the scope of this work. But a brief description of the battle is necessary to understand the setting of its final hours.

Doorman’s general plan, it seems, was to keep the Combined Striking Force between the Japanese and the Java coast, while making periodic thrusts north to try to catch the convoy. The Japanese intent was both to protect the convoy, using its warships as a screen, and neutralize the remaining ABDA naval assets.

Informed of Doorman’s turnabout, Takagi raced to cut off the Allied approach to the invasion convoy. Takagi was a submariner by training and it showed in his conduct in this battle. Takagi and his staff also seem to have been unusually nervous by normal Japanese or combat officer standards, and seemed aghast that their wartime enemies were actually shooting at them.[27] Hara Tameichi, who commanded the Japanese destroyer Amatsukaze during the battle, wrote his memoirs Japanese Destroyer Captain after the war. His portrayal of Takagi therein is unflattering: an arrogant, cocky and haughty commander. Takagi grumbled at being forced to intercept Doorman, as in his wisdom he had been “escorting” the convoy from 200 miles behind them.[28] Takagi had to race to catch up and got to the battlefield just as both sides sighted each other.

Nevertheless, Takagi managed to block the Combined Striking Force’s initial approach to the convoy. Forced by communication issues to keep his cruisers in a column, Doorman thrust blindly northwest, amazingly enough in the direction of the convoy. With only the 8-inch guns of Exeter and Houston possessing the necessary range, the Allies engaged the Japanese in a long-range but ineffectual gun duel. Doorman attempted to close the range to enable his light cruisers to engage. But Takagi threatened to “cross the T” of the ABDA column.[29] Doorman was thus forced to turn and close at a much slower pace to attempt to bring his 6-inch guns into range.

With the severe communication issues, Doorman had little choice but to give the Allied ships his famous order “Follow me,” and have them follow him like insect segments from the video game Centipede. And like the video game Centipede, these segments were picked off one by one:

Exeter – An 8-inch shell from Haguro crashed through a gun mount and exploded in a boiler, knocking 5 of her 6 boilers off line and reducing her speed to between 5 and 10 knots. Spewing forth white steam from her damaged boilers, Exeter sheered out of column so Houston behind her would not plow into her stern. But the steam obscured the leading De Ruyter from the remainder of the column, who thought they had missed an order to immediately turn, and they turned out of column just as Exeter had done, throwing the Combined Striking Force into confusion. Ultimately, Exeter was ordered to retire to Soerabaja.

Kortenaer – The Allied cruisers were thrown into confusion in the path of oncoming Japanese torpedoes. While a number of the torpedoes exploded prematurely, one – also from the Haguro – struck Lieutenant Commander A. Kroese’s Kortenaer amidships.[30] Her back broken, the destroyer jack-knifed, capsized and sank in a matter of minutes. Not comprehending the torpedoes in their midst had come from the Japanese ships – the Allies had no idea of the extreme range of the Type 93; every Japanese cruiser and destroyer carried torpedoes, and most, also unbeknownst to the Allies, even carried one set of reloads – the Allied crews were convinced they had been ambushed by Japanese submarines.

Electra – To protect Exeter, Doorman signaled “Counterattack” to the British destroyers.[31] While too scattered to mount a coordinated torpedo attack, Electra, Encounter and Jupiter moved to protect Exeter, supported by Witte de With. Electra, having just laid a smoke screen for Exeter, now charged into that smoke screen – and came out on the other side to face the entire Japanese 2nd Destroyer flotilla and part of the 4th. Though she managed to temporarily disable the destroyer Asagumo, Electra’s engines were knocked out by an early hit and her guns were picked off one by one, with Jintsu administering particular torment. She would succumb to the pounding.

Witte de With – While charging to support the British destroyers, Witte de With was taking the opportunity to drop depth charges on the supposed Japanese submarines. During high-speed maneuvering, one of the readied depth charges was swept overboard and detonated under the destroyer’s stern, damaging her propellers and knocking out two electrical generators.[32] Whether Witte de With was battle-worthy or sea-worthy after this incident is unclear. She was ordered to escort Exeter to Soerabaja, where she entered drydock, but was not repaired before the Dutch had to abandon the port and consequently was scuttled.

John D. Edwards, Alden, John D. Ford, Paul Jones – With darkness approaching, Doorman was eager to shake the Japanese escorts and find the convoy. Apparently Doorman took his orders literally and did not consider that by destroying enough of the escorts he could force the convoy to turn back, a sign of Doorman’s relative inexperience, which he shared with most American commanders at this stage of the war. After a confusing series of orders and countermands, Doorman ordered US Destroyer Squadron 58 to “cover my retirement.” DesRon 58 Commander Thomas Binford had no idea what that meant, but with his fuel running dangerously low and not wanting to return to base without firing his torpedoes in anger, he launched a long-range torpedo attack that forced the Japanese to turn away. No hits were scored; whether this was because of the range, Japanese evasion or the almost complete ineffectiveness of US torpedoes is unclear. As it turns out, Binford did exactly what Doorman had wanted and left the Dutch admiral impressed with Binford’s work.[33]

Thus temporarily freed from the engagement, Doorman thrust to the north at dusk before giving up, again typical of Dutch luck, when he was only 20 miles away from the convoy – just over the horizon to the northwest. The US destroyers followed Doorman southward until the Allied column reached the Java coast, then with fuel almost gone, returned to Soerabaja.[34]

It is at this perhaps unusual point that our story begins in earnest, for it is here that one can begin the identification of a subtle but conspicuously missing thread of the last hours of the battle – recorded communications. And it begins with what is probably one of the most freakish incidents of the war.

The loss of Jupiter

Doorman’s turn to the south when, unbeknownst to him, his objective was only 20 miles away was the result of his complete lack of intelligence as to the Japanese movements and dispositions. Doorman had an unfortunate habit of keeping his plans to himself, so it is not possible to know for certain what he was thinking. But if the information and considerations Doorman had are examined, it is possible to assemble a likely scenario of what the unfortunate Dutch admiral was attempting to do during these last hours of his life.

In turning to the south, Doorman had likely despaired of finding the convoy by poking blindly, randomly in the dark in the middle of the Java Sea. He does appear to have developed a better idea: go to the convoy’s landing site and work back along their projected course track.

And Allied intelligence had a prediction of the convoy’s landing site: Toeban (Tuban) Bay, on Java’s northern coast about 50 miles west of the channel to Soerabaja. To prepare for the predicted landing, a Dutch infantry contingent had been stationed at Toeban, and Admiral Helfrich had ordered the minelayer Gouden Leeuw to lay a minefield at the southern end of the bay. Doorman was informed of these developments.

That the prediction of the Japanese convoy landing at Toeban was little more than an educated guess mattered little. It was not necessarily good information, but it was the best the Allies had, the best Doorman had, and so his best remaining option was to act on it. The placement of the infantry would prove to be fortuitous, though not for reasons the Dutch had been considering; the minefield not so much.

When the Allied column reached the Java coast after dark, Doorman had them turn westward heading for Toeban, hugging the coast in the hopes of evading the notice of the Japanese while staying positioned between the Japanese and the coast. It was a futile effort; Japanese float planes shadowed the Combined Striking Force in the moonlight. At least by heading to the Japanese landing site the Allies had partially nullified the advantage given by the float planes; if the convoy was headed to Toeban it had only a limited number of maneuvers it could make. But the float planes did mean there would be a fight. So persistent were the float planes that the normally calm, stoic Doorman cursed them softly under his breath.[35]

By this time, the Combined Striking Force had been reduced to a column led by De Ruyter, followed by Perth, Houston, Java and Jupiter. Encounter was still operational and was trying to catch up to the cruiser column after being separated while screening Exeter, but she was well out of sight and so far behind that she was of little tactical use.

Together this little column steamed along close to the Java coast, too close for Captain Rooks of Houston. Being the heaviest remaining ship and the only heavy cruiser left, Houston had a deeper draught than the other ships. Captain Rooks grew concerned that the water was too shallow for Houston and swung the heavy cruiser out of column onto an offset course – parallel to that of the other four squadron mates.[36] It may have saved his ship.

At around 9:00 pm, as the Allied column passed north of Toeban Bay, Jupiter, last in the column, suffered an underwater explosion on her starboard side that wrecked her No. 2 engine room and caused her to lose all power. She blinkered a signal to Java ahead of “Jupiter torpedoed,” presumably by a Japanese submarine. Doorman apparently checked on the big British destroyer, but with no power to pump out the water pouring into her hull or to even move, her wound was mortal. Fortunately, Jupiter was disabled so close to the Java coast that almost her entire crew was rescued from drowning, helped by the presence of the Dutch army contingent. Either seeing or otherwise being convinced that the destroyer was close enough to shore to save most of the crew, Doorman continued onward to the west.[39] Jupiter sank at 1:30 the next morning.

The cause of Jupiter’s loss has never been conclusively determined. Japanese records examined postwar showed no submarine in the area. The most recent scholarship strongly suggests that Jupiter was the victim of a discarded Dutch mine: Gouden Leeuw never laid the minefield in the southern end of Toeban Bay as ordered, but en route instead just dumped the mines, only a few of which were active, well north of their assigned position.[40]

Thus, it appears that, again, typical of Dutch luck and reversing Doorman’s luck with mines earlier, the Combined Striking Force just happened to sail through a patch of mines, only a few of which were armed, that had been unceremoniously dumped. And one of those few that were armed just happened to strike a fatal blow against the big, new, overstrength British destroyer Jupiter. If this scenario is correct, it would be one of the most freakish accidents of the war.

The question of how Jupiter was sunk is only the most prominent of the questions about this incident, but there are others. How was Admiral Doorman informed of Jupiter’s plight? How was he able to check on her condition? There are several plausible scenarios, but none of the available battle reports or survivors’ accounts even hint at a definitive solution.

By most standards, this issue would seem trivial, and understandably so. Normally. Clearly, Doorman was informed of the situation. Clearly he was able to check on it. But how is not recorded. The communications to him and from him are not recorded.

This is an issue that repeats itself throughout these last hours of the Combined Striking Force: communications that obviously took place, but the record makes no mention of them. They are most clearly shown in next incident.

Passing the Kortenaer and the “Magnificent” Dash

Having passed Toeban Bay and not found the Japanese convoy, Doorman proceeded to work his way back along the convoy’s projected route. De Ruyter led the column on a starboard turn to the north on a base course 0 degrees True.[41] Doorman had the column run at very high speed and, without orders, zig zag slightly. This was a tactic normally used to throw off submarine firing solutions, though at the expense of staying in the vicinity of the submarine. In this case, Doorman probably wanted to confuse the trailing Japanese float planes as well. In this, once again, he failed. The planes continued to spy on the Allied cruisers, dropping magnesium flares attached to little parachutes to backlight the cruisers themselves, and calcium float lights that burned on water to mark their course.

This northward thrust had them cross the area of the afternoon action, and pass the survivors of the sunken destroyer Kortenaer, still trying to survive on the sea. Kortenaer’s skipper A. Kroese, in his book The Dutch Navy at War, relates the experience of one of these survivors:

About midnight we heard the sound of movement on the water. We looked up and suddenly we saw, clearly outlined in the moonlight, the shape of ships making straight for us. Would we be picked up? The ships loomed nearer, obviously going at top speed. Soon we saw the rising water foaming at the bows. Still they continued on their course directly towards us. But this was getting dangerous! These were not rescuers, but monsters which threatened to destroy us. They were going to run us down in their mad career and crush us in their furiously churning propellers. About midnight we heard the sound of movement on the water. We looked up and suddenly we saw, clearly outlined in the moonlight, the shape of ships making straight for us. Would we be picked up? The ships loomed nearer, obviously going at top speed. Soon we saw the rising water foaming at the bows. Still they continued on their course directly towards us. But this was getting dangerous! These were not rescuers, but monsters which threatened to destroy us. They were going to run us down in their mad career and crush us in their furiously churning propellers.

We yelled like madmen, not to be picked up but to warn them off. And then suddenly we saw that they were our own cruisers racing along in the moonlit tropical night. Probably they saw us, too, for the leading De Ruyter changed course slightly. As they charged past us, almost touching us, the rafts were turned over and over in the wash. But we cheered and shouted, for there high on the gun turrets we could clearly see our comrades. In the noise and turmoil they raced past – the Dutchman, the Australian, the American, and last another Dutchman, four cruisers going at top speed under a tropical moon. I did not know that it could be such an impressive spectacle. While they were speeding past, some Americans on the Houston’s stern dropped a flare. It floated on the water, a dancing flame on the sea. We followed the ships with our eyes until they were out of sight. They had no destroyer protection any longer and their course was north towards the enemy. Had Rear Admiral Doorman from his bridge on the flagship looked down on us with his quiet smile and given us a sympathetic thought? “This is the last time we have seen them,” said one of the officers of the Kortenaer as the ships faded from sight. “I hope they smash the ribs of the Japs before they go down themselves,” said a sergeant vindictively, and from the bottom of his heart, added “The bastards!” All was quiet again around us. Near us danced the flare. We couldn’t take our eyes off it, for it was like a flame of hope. Slowly the hours passed. Then another ship appeared above [sic] the horizon. First we saw it from the beam. Suddenly the vessel changed course and came straight for us. It was some lonely destroyer or small cruiser, seeming a straggler in this sea full of action. Perhaps it was a Jap that had been damaged and was now withdrawing from the scene of battle. We had not been in the water long enough in sea to appreciate being picked up by the enemy to be made prisoners of war. Intently and suspiciously, we watched the approaching ship. “An English destroyer,” shouted one of the officers. “It’s the Encounter,” shouted another. We all stared silently, then a shout of relief and joy broke out. It was the Encounter! It almost seemed as if the flare from the Houston shared our joy and danced with pleasure, too. Cleverly, the Commander of the Encounter maneuvered his ship alongside the rafts. Nets were dropped, and all who could climb swarmed monkey-like up the ropes. The wounded and those who were too weak had to be hauled aboard. When we all had the firm deck of the destroyer under us, our hearts overflowed with gratitude. We could have hugged the British sailors, but even if that’s what you are feeling, you can’t just show it. You give your rescuers a firm hand-shake, and let them see that you appreciate very much the glass of grog they give you and the warm, dry clothes they provide from their own scanty wardrobes. “Bad luck!” said the British sailors, shaking their heads because we had lost our ship. Poor fellows! The next night Encounter went down and there were no Allied ships left to pick up her survivors.[42] The next morning, February 28, Encounter disembarked us in Soerabaja. A Dutch patrol boat brought us to shore .....[43] |

This would be the last time anyone would see the Combined Striking Force before its final battle.[44]

This rather simple-sounding incident has its own murkiness, encapsulated by one deceptively simple question: Who ordered Encounter to rescue the survivors of Kortenaer?

The sources disagree on the answer to this simple question. Some, mainly Anglo, sources say that Perth’s Captain Waller ordered Encounter to pick up the survivors. Other, mainly Dutch sources, assert that it was Admiral Doorman. The ONI Narrative sidesteps the issue by using the passive voice, stating Encounter “was ordered” to pick them up. Hornfischer’s work says Encounter “stopped” to pick them up but adds “on whose authority is unclear.”[46]

This incident highlights the further deterioration of already tenuous communications within the Combined Striking Force, but also shows that much of what communication there was, was not recorded.

At some point during the evening, the voice radio used on De Ruyter for communication with the other ships in the task force – a very high frequency, short-to-medium range device known as “Talk Between Ships” or “TBS” – went out.[47 An identical Dutch TBS radio installed on Houston to streamline communications went off-line as well.[48] The cause of these radio malfunctions, which was common in this early part of the Pacific War, was the same – the concussion caused by the firing of the main guns. The Battle of the Java Sea was the first action in which De Ruyter and Houston had fired their main armaments for extended periods, and the vibrations they caused threw off the delicate settings of the radios.[49]

And that was by no means the end of De Ruyter’s communications problems. During the afternoon action, Doorman had frequently given orders by flags run up the cruiser’s mast – his famous command “Follow Me” was often in the form of a flag. But it was almost impossible to see flags at night. Signal by semaphore was similarly useless. A favorite method of communications at night involved the use of mounted blinker lights. Unfortunately, the same gun concussions that had knocked out De Ruyter’s TBS radio had also shattered her mounted blinker lights.[50] De Ruyter’s massive searchlights, which could have been similarly used, were similarly shattered by the concussions.[51] The only method left to Doorman for communicating with his force was by use of a small, hand-held blinker lamp, known as an “Aldis lamp,” flashing signals in plain English.[52]

What seems to have happened is that Doorman, because he had no voice radio, signaled Perth to use her radio to have Kortenaer’s survivors picked up. Doorman had the authority to order the survivors picked up, but not the means. Waller had the means to order the survivors picked up, but not the authority. Doorman’s signal may have gone straight to Perth’s radio room, without Waller being made aware of it.[53] What is known for certain is a TBS message to that effect was sent out by Perth shortly thereafter.[54] Encounter picked up the message and acted on it.[55] Houston had apparently also been informed that the survivors were to be picked up and tossed out a “light” or, as other translations call it, a “flare.” The latter would probably be a calcium floatlight that burned on the water, similar to what the Japanese were using to track the Allied column; the former likely a small lighted buoy. Houston’s intent here was to mark the position and make it easier to find in the darkness.

By now, the Japanese floatplanes had been forced to retire for lack of fuel, so now Takagi’s advantage of knowing Doorman’s movements was gone. The Combined Striking Force and the Japanese were now equally blind as to each other’s movements. The Allies could have even had an advantage here as P-5, a Catalina with the US Patrol Wing 10, was aloft that night, and did spot the Japanese convoy in the moonlight. P-5 transmitted the convoy’s position to Naval Commander Soerabaja and continued to shadow it, but could Naval Commander Soerabaja get that information to Doorman in time?

Indeed, even with both forces “equally” blind, Doorman had a small advantage, if only he had realized it. Takagi knew the Allies’ last course, courtesy of his float planes. A radical change of course after the withdrawal of the float planes might have left the cocky Takagi fumbling to find the Allied cruisers once again. But without knowledge of the convoy’s location, such a move would have been a dicey proposition.

And so, in desperation, having passed Toeban Bay, Doorman made his last dash north to find the convoy, hoping he had outflanked them to the west.[57] “He had no idea how close he came in this last magnificent attempt.” So says the ONI Narrative, adding a small bit of hyperbole to an otherwise dry missive. But it is not out of place. With four ships, dead tired, low on ammunition and outnumbered, Doorman’s attempt to strike the convoy was the naval version of Thermopylae, if ultimately less successful.

As now the final chapter began at 11:15 pm, when De Ruyter signaled to Perth behind her, “Target at port. Four points.”[58] The Dutch cruiser’s lookouts had sighted Nachi and Haguro in the moonlight, 45 degrees off the port bow at a distance of about 9,000 yards.

A Running Gun Battle

It is at this point that the reports and other evidence become much more ambiguous or even contradictory. No one agrees on when events took place in relation to other events or in some cases whether those events occurred at all. This is understandable, for much of the evidence for this last phase of the battle consists of eyewitness testimony, normally the least reliable form of evidence in the best of times, and notoriously unreliable in times of extreme stress, for which the Battle of the Java Sea certainly qualifies. Perceptions of time suffer especially in such situations. As such, it is literally impossible to give complete effect to all of reports and testimony.

Presumably for that reason, most histories have only given a quick or general description of the last encounter between the ABDA Combined Striking Force and the Japanese Sentai 5. Here I will try to give as many specifics as possible and try to fill the remaining holes (for there are holes), with deduction, educated guesses and, (hopefully only) when all other options fail, informed speculation, while trying to give as much effect to the as many of the available reports as possible.

For much of the war, the specially-trained and equipped Japanese lookouts, who used oversized and polarized binoculars, would outperform even American radar. Here, where neither the Americans nor their allies had radar, the Japanese had already spotted the cruiser column at 11:03 pm at 16,000 yards.[60] Sentai 5 was in column on a course 180 degrees True – due south. Some sources indicate the Japanese had taken the Combined Striking Force under fire even before De Ruyter spotted the cruisers, but if so the fire was completely ineffective, as the Allied reports do not even mention it.

The situation for the Japanese appears to have been trickier than is generally recognized. Tanaka, whose 2nd Destroyer Flotilla had been screening the convoy to the west northwest, ordered a course reversal to a northeasterly heading, keeping his squadron between the Allies and the convoy. According to Hara, Takagi, still headed due south, ordered Sentai 5 to slow down so he could develop a good firing angle for his torpedoes.[61] The secondary battery (5-inch) of Houston fired starshells at a range of 10,000 yards. Starshells – illumination rounds – are intended to reveal a target by backlighting it, but in order to silhouette a target starshells need to burst behind it. Houston’s starshells fell short. The American cruiser fired two more salvoes of illumination rounds, this time at a range of 14,000 yards. These, too, fell short.[62] The Japanese fired illumination rounds of their own. These fell short as well, but the Allies’ terrible luck held: the glare of the Japanese starshells concealed Nachi and Haguro behind them, basically blinding the Allied gunners.[63]

Takagi may have intended to launch torpedoes at this point, because he would have had a good firing solution for his Long Lances, but he did not for reasons that remain vague. He may have underestimated the Allied column’s speed or, more likely, he was concerned that a torpedo launch might move his cruisers out of position blocking the convoy and allow Doorman to get behind him. As it was, Doorman was able to get slightly north of the Takagi’s cruisers by perhaps a little more than one mile – not enough to make a difference.[64] Nachi and Haguro turned to starboard, poured on speed, and spent the next twenty minutes trying to close the range with the Combined Striking Force.[65]

What followed next was the naval equivalent of two exhausted football teams fighting it out in a sudden death overtime of the most literal kind – a slow exchange of fire as the Japanese labored to close the range. Java kept her guns trained on the Japanese, but since she was outranged – again – she did not fire.[66] Houston ahead of her was down to less than 300 rounds of 8-inch ammunition – 50 per functional gun – a fact which, due to Houston’s lack of a functioning TBS radio, had to be relayed to Doorman by Perth.[67] In response Doorman ordered Houston not to fire unless she could be certain of a hit. In the action she fired once.

So this last confrontation was between the 8-inch Japanese heavy cruisers Nachi and Haguro and the 6-inch Allied light cruisers

De Ruyter and Java. Not an even match. As it had been through the day, Japanese gunfire was tightly spaced and accurate.

Houston was dangerously straddled. One shell came so close to De Ruyter that the other ships thought she had been hit on her quarterdeck, but Dutch accounts make no mention of such a hit.

So this last confrontation was between the 8-inch Japanese heavy cruisers Nachi and Haguro and the 6-inch Allied light cruisers

De Ruyter and Java. Not an even match. As it had been through the day, Japanese gunfire was tightly spaced and accurate.

Houston was dangerously straddled. One shell came so close to De Ruyter that the other ships thought she had been hit on her quarterdeck, but Dutch accounts make no mention of such a hit.

The exchange of gunfire, a violent contrast to the peaceful, even romantic backdrop of the bright moon and stars, was slow and sporadic, a result of the dwindling supply of ammunition and the crews’ exhaustion. By this time, the battle had taken seven hours and both sides were extremely tired, the Allies much moreso for having been at battle stations 24 hours beforehand. Having to work the manual labor part of the battle, the gun crews on both sides had had an especially tiring day.

So it is not surprising that the exchange of fire here was slow. So slow was the exchange that it took a moment to register when the Japanese actually stopped firing.

Now why would they do that?

Karel Doorman knew why – the Japanese had launched torpedoes.[68]

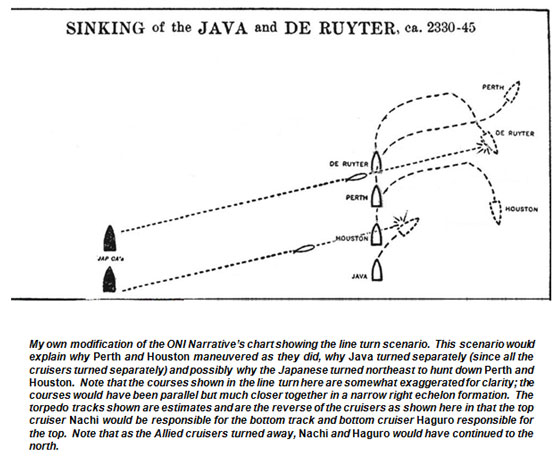

The Line Turn

Japanese tactical doctrine called for an ambush of enemy forces in a night attack using torpedoes before opening gunfire. Nihon Kaigun used this doctrine very effectively during the war in places such as Savo Island and Tassafaronga. But the doctrine depends on the element of surprise, meaning you are not supposed to tip off the enemy that you are launching torpedoes – which is precisely what Takagi did by ceasing fire.[69]

Thus informed, Doorman did exactly what he was supposed to do: ordered an immediate 90-degree turn to starboard in an attempt to comb the torpedoes – that is, turn to a course parallel to that of the torpedoes to present a narrow stern (preferably) or bow profile (as opposed to a wide beam profile) and thus minimizing the chances of a hit.[70] Because each ship was to turn as fast as possible, the result would be a breaking of the column and would result instead in a line of ships four abreast headed east – what is sometimes called a “line turn,” a “simultaneous turn” or an “echelon turn.”[71] Waller does not record whether such an order was flashed back to Perth, but he did not need the order: the wily veteran had figured out what was going on and ordered Perth into an immediate 90-degree turn to starboard, conforming to De Ruyter’s turn and leaving Perth behind and somewhat to starboard of the flagship.

One way or another, word was passed back to Houston, who began her own 90-turn to starboard.[72] Word reached Java, 900 yards astern of Houston.[73] Java began her turn …

But Java would never finish her turn.[74] Time had run out.

Too Late

At 11:32 pm, while early in her turn, Java suffered an underwater explosion port side aft, the end result of one of eight torpedoes fired ten minutes earlier by Nachi.[75] Now the cows of Java’s aged design – poor internal compartmentalization, obsolete gun layout – would come home to roost.

“Almost simultaneous” with the first explosion came a second.[76] This blast was not so much larger than the first as it was cataclysmic, sending a huge fireball into the night sky. Horrified lookouts on Houston saw “bodies flying through the air, silhouetted by flames, the water burning.”[77] The blast was actually felt by crewman aboard Perth.[78] And in a mass of smoke and fire, the stern of Java disappeared.

Literally. When the smoke cleared enough to see, Java now ended in an abruptly blazing, “jagged,” “tangled mess.”[79] Nachi’s torpedo had caused Java’s aft magazine, not nearly as well protected as those of her more modern brethren, to explode, blowing off some 100 feet of the cruiser’s stern.

There was no hope for the ship; the truncated stern section could not be sealed off and the engine room was flooding.[80] Captain van Straelen gave the order to abandon ship, but Java was settling so rapidly there was no time to launch the lifeboats. The fire had also consumed most of Java’s life vests. Crewmen tossed anything overboard that might float and then jumped after them. Less than fifteen minutes after the devastating torpedo hit, the bow of Java reared up and the shattered stern led the rest of the ship to the depths. Out of a crew of 528, only nineteen survived.

One can only wonder at the thoughts of Admiral Doorman, helplessly watching the fiery end of this old cruiser that had served under him for so many years. Karel Doorman cared deeply for the men under his command, whether they were Dutch or Anglo. He took every precaution to protect them, did everything he could to make sure that his men were not sacrificed for nothing, so much so that he was branded a coward. So much so that even after he ordered survivors of sunk or disabled ships to be left “to the mercy of the enemy” he avoided doing so when he could – screening the staggering Exeter and giving her an escort home, checking to make sure the crew of the dying Jupiter was going to be okay, and even giving up his last, badly-needed destroyer, Encounter, to pick up the half-drowned survivors of Kortenaer. Every casualty had to affect him deeply.

For the mortified crewmen of Houston, their horror was mixed with a sense of bewilderment. Captain Rooks had to maneuver the ship to avoid torpedoes “that zipped past us 10 feet on either side.”[81] But where had they come from? They were still unaware of the range and capabilities of the Japanese Type 93 torpedo, and Nachi and Haguro had disappeared into a rain squall. A number of the crew believed they had run into a submarine ambush.

In watching the end of Java, the one thought that had to run through their minds was “There but for the grace of God go we.” Houston’s own No. 3 turret had been disabled by a bomb hit three weeks earlier that had also killed 50 men, a fact not lost on Admiral Doorman and the big reason he was reluctant to sortie under threat of air attack.[82] The bomb had started a fire in the turret that nearly reached the No. 3 magazine beneath it. If it had done so, Houston’s stern would likely have been blown off and she would have suffered a fate similar to that of Java. As it was, she was lucky to escape with only a gutted, useless turret.

So the men aboard Houston could be forgiven for being transfixed on the catastrophe behind them, so much so that they were in danger of missing the catastrophe unfolding in front of them.

A Turn Too Far

While the loss of Java was devastating, it could have been a lot worse. Doorman guessing what the cessation of Japanese gunfire meant and acting quickly on that guess with the 90-degree starboard turn had likely saved his other three ships. His northward column was now a narrow right echelon formation – De Ruyter in front, with Perth behind her and to starboard, and Houston behind Perth and further to starboard – headed east. He decided it was time to reform the column.

As he had twice earlier in the day, Doorman would reform the column by having his flagship basically circle his remaining ships so they could fall in behind him. De Ruyter would turn to starboard and cross the bow of Perth, after which Perth would turn to starboard and fall in behind. Then both ships would cross in front of Houston, who would then fall in behind Perth. To that end, Doorman ordered De Ruyter to make a further turn to starboard, either in a continuation of the original turn or as the start of a new turn.[83]

Because this turn would take De Ruyter across the track the Japanese torpedoes had followed, Doorman must have been convinced that the threat of the Japanese torpedoes had passed. Possibly his staff had made calculations based on the estimated firing time and torpedo track.[84] More likely, De Ruyter’s lookouts had seen torpedoes pass by; as it was, Houston had watched torpedoes bracket the US cruiser. Doorman clearly believed the torpedoes had passed. And, indeed, those remaining from Nachi had actually passed the column and were churning away from the action.

So De Ruyter turned to the southeast, her forward guns swinging around to starboard to remain trained on the Japanese cruisers, apparently convinced the immediate danger had ended.

Which is why there was surprise and extreme consternation on the bridge of De Ruyter when a telegrapher spotted wakes approaching from relative bearing 135 degrees.[86]

“What is that!?!?” The response from Admiral Doorman was calm and matter-of-fact.

“Oh, that? That’s a torpedo …”[87]

The flagship was still turning to starboard when a Type 93 lanced into the starboard side aft, near her reduction gearing.[88] A member of the Dutch Marine Corps remembered, “It was like the ship was lifted from the water; all lights went out, we were listing heavily and fire broke out on the AA-deck…”[89]

De Ruyter was the victim of something of a freak hit. She had been the victim of one of four torpedoes fired by Haguro. Haguro had fired her spread at 11:23 pm, one minute after Nachi.[90] That one-minute differential had allowed Haguro, running at high speed, to overtake Nachi’s original firing position and maybe to even apparently pass it. As a result, Haguro’s torpedoes had overlapped with Nachi’s torpedo track.[91] Doorman’s quick action to reform the column was too quick, as he had unknowingly led his flagship right into the path of Haguro’s deadly fish. Whether the one-minute differential was intentional is a mystery.

But the result was not. Haguro’s torpedo does not seem to have been immediately fatal to the positive buoyancy of De Ruyter, but it might as well have been. As noted earlier, the cruiser lost power, because the hit had knocked out the turbines. The explosion started a fire that spread with extraordinary speed, and within minutes everything aft of the catapult was an inferno. Why the fire spread so quickly is unclear. What is known is that one of the ship’s oil tanks had ruptured and probably leaked flammable bunker fuel both inside and outside the ship. The antiaircraft deck was also rapidly succumbing to the spread of the fire.[92] There the fire was especially dangerous, as it contained the five twin-barreled 40-mm Bofors antiaircraft mounts – and ready lockers full of 40-mm ammunition, which presently began to explode with devastating effect.[93] Walter Winslow remembered, “[A]mmunition, detonated by the intense heat, sent white-hot fragments flying into the night sky like demonic fireworks.”[94]

The cruiser’s damage control teams went to work and may have kept it from immediately sinking, but the damage to the generators, now engulfed in flames, meant no power for water pumps for firefighting or reversing the flooding. De Ruyter was in a fatal conundrum – you could not put out the fire without restoring power, yet you could not restore power without putting out the fire. The ship was doomed.

As if to emphasize the point, the fire on the antiaircraft deck reached the cruiser’s pyrotechnics locker, and flares, signal rockets and starshells shot into the sky in a ghoulish fireworks display.[95]

The order to abandon ship was given. Captain Lacomblé lamented, “Now it’s all over ...”[96]

|

But it was not over, not yet, for Perth and Houston. How long it remained that way this night remained to be seen, for De Ruyter had been crossing in front of the two cruisers, cutting it rather close, in an attempt to reform the column. When the flagship lost power she staggered to a halt – right in the path of the speeding Anglo cruisers.

For Captain Rooks of Houston, aft of and starboard of Perth, the decision was easy. Houston turned to starboard and came within 100 yards of the stricken flagship’s starboard side and bow before heading off to the southeast.[97]

With the Dutch flagship’s bow pointed to the southeast, away from both Anglo cruisers, a starboard turn would have been the preferred choice for Perth’s Captain Waller … but for the presence of Houston. A starboard turn by Perth would have sharpened Houston’s starboard turn, and given both cruisers’ high rate of speed would have almost guaranteed a very damaging collision for the only remaining operational Allied ships in the Java Sea.

The only other option available to avoid shearing off De Ruyter’s blazing stern, which was pointed northwest toward Perth, was a very, very sharp port turn. Waller had to shut down one of his port engines to enable his starboard engines torsion to swing the ship’s bow over further to port.[98 Perth came so close to De Ruyter as to feel the heat of the flames and “smell burning paint and a horrible stink like burning bodies.”[99] But she managed to clear the Dutch cruiser’s stern and head northeast. This desperate swerve may have had an interesting consequence.

On the cruisers of Sentai 5, now northwest of the remnants of the Combined Striking Force, the crews were able to see the explosions of De Ruyter and Java through the rain, and filled the drizzly air with dancing and shouts of “Banzai!”[100] Admiral Takagi determined the Dutch cruisers to be finished. Hoping to finish off the Allied ships, Takagi had Nachi and Haguro dash in what he thought was pursuit – to the northeast. Hara called it Takagi’s last mistake of the battle.[101] Why he chose northeast has never been determined; it seems Nachi may have seen Perth, backlit by the burning De Ruyter, in her port swerve to the northeast and may have followed.[102]

|

But Captain Waller had no intention of continuing to the northeast. He had Perth reverse course, likely to port to keep from being silhouetted again, and head toward the stricken flagship, slowing down slightly. One may speculate here that Houston, already headed southeast, also slowed down and probably turned to port. Both Waller and Rooks wanted to check on the status of the obviously troubled De Ruyter and find out what Doorman wanted to do. Doorman had given orders that disabled ships and surviving crews were to be left “to the mercy of the enemy.” But now it was he who would be left behind, who needed saving. Would he change his orders now?

An Aldis lamp on De Ruyter flashed their answer – “Proceed to Batavia. Do not stop to attempt rescue of us.”[103]

While the use of the Aldis lamp requires brevity – “grim and to the point” was how one historian described this message – neither the format nor his innate stoicism could take away from the meaning of this last order of Rear Admiral Karel Doorman, and it has not gotten the attention it deserves.[104]

In movies, it is almost cliché for a soldier to give his life for his comrades, even to shout at them, “Forget about me! Save yourselves!” Yet this was one real-life case where it actually happened. A commanding officer, no less. A commanding officer whose courage had been questioned and ridiculed, telling the remaining ships under his command to leave him behind and save themselves – ships that were not even of his country and whose crews had been among those who had criticized him. Not only did he tell them to save themselves, he ordered them to do so, giving them legal cover for doing so and hopefully sparing Captain Waller any feelings of guilt for seemingly having abandoned the cruiser’s survivors. Whatever the faults of Karel Doorman, he deserves hero status for this one selfless act.

The nobility of the gesture was certainly not lost on Captain Waller, but he had other issues to worry about. Captain Waller says that at this point as senior surviving officer he “took Houston under [his] orders,” but exactly what this means is unclear.[105] He probably signaled Houston to continue heading southeast and Perth would catch up. At around midnight, Perth caught up to her American brethren, but in a fashion much more dramatic than anyone would have preferred.[106]

Houston was speeding to the southeast towards Soerabaja when her lookouts thought they spotted torpedoes – it bears remembering here that all day the crews, not knowing the capabilities of the Japanese Type 93 torpedo, had thought they were being stalked by submarines, who in their minds had claimed Kortenaer, Jupiter and now Java and De Ruyter. Now here were more, or so it seemed.

Captain Rooks ordered a hard turn to starboard to avoid the torpedoes – except there were no torpedoes and Perth was trying to pass the American cruiser to starboard to take the lead position in this now two-ship column. Captain Waller’s difficult turn to avoid De Ruyter and Houston would have been for naught but for a member of Houston’s bridge crew, who literally pushed the helmsman aside, seized the wheel and swung it to port. Collision was avoided by 25 yards.[107]

Captains Waller and Rooks took the opportunity of this meeting to discuss their options. Waller recommended they head to Batavia at 20 knots; Rooks countered that they should head there at 30 knots.[108]

And so, as the history books claim, Perth and Houston sped off “into the night” and their own date with destiny and legend, leaving behind the blazing hulk of De Ruyter. Before Houston lost sight of the Dutch flagship over the horizon, her lookouts had counted nine separate explosions.[110]

At about this time, to add insult to grievous injury, Naval Commander Soerabaja sent out the following signal:

| Convoy concentrated to 39 transports in two column, 1500 yards between columns, course north, speed ten. 3 destroyers in column right flank, 1000 yards. 1 cruiser, 2 destroyers in column left flank 1000 yards. 2 cruisers and six destroyers concentrating on convoy at high speed positions probably, Lat 05-36S, Long 112-46E/0227 1842. |

The irony is worthy of Alannis Morrisette. The information the Combined Striking Force had been waiting for all day and night was finally available – 20 minutes too late. Now the Combined Striking Force was in no shape to act on it. What would have been precious news was now useless to the beleaguered Admiral Doorman.

Now the Dutch admiral could only oversee the evacuation of the glowing blast furnace that his flagship had become. Amidst the continuing explosions and with the power out, lowering lifeboats and other life preserving equipment was next to impossible. Nevertheless, Doorman could be seen assisting the wounded and giving encouragement to his crew. Not all of the wounded were able to leave, however, and the ship’s surgeon chose to stay with them and share their fate.

So did Karel Doorman. His work finished, he returned to the bridge and was never seen again.

Still aloft was P-5, the US PBY Catalina flying boat that had found the convoy and done its best to get the information to those who needed it most. As it was returning home, it spotted several sharp flashes in the distance, followed by several heavy explosions. Then it spotted two ships in the moonlight, leaving the area at high speed. P-5 dutifully reported the sighting, and wondered what it meant.[111]

On the north coast of Java, people were wondering what was behind the ominous sounds they had been hearing throughout the night from far out to sea. Many thought it was a storm; indeed it was, though not of the meteorological variety. Others, like one American B-17 pilot, knew better: “I could hear a dull rumble in the midnight air coming from far over the water. The people in the blacked-out streets assumed it was distant thunder. I knew it was the little Dutch Navy in its final agony out there in the dark.”[112] Said another pilot, “Java died that night in the gunfire which came rolling in over the water.”[113]

Gunfire and explosions. The sounds would end that night when De Ruyter, the repeated blasts having ruptured her hull, the raging inferno having heated it to near-incandescence, slipped beneath the dark waters of the Java Sea with an unpleasant steaming hiss. The time was 2:30 am.[114]

| * * * |

Show Notes

Footnotes

[1]. See, e.g., Edwin P. Hoyt, The Lonely Ships: The Life and Death of the US Asiatic Fleet, New York, David McKay, p. 257; W.G. Winslow, The Ghost That Died At Sunda Strait (“Ghost”), Annapolis, Naval Institute Press, 1984, p. 125.

[2]. J.A. Collins, Commodore, RAN, “Reports on the Battle of the Java Sea,” in Ronald McKie, Proud Echo, London, Robert Hale, 1953, p. 135.

[3]. See, e.g. Winslow, The Fleet the Gods Forgot (“Fleet”), Annapolis, Naval Institute Press, 1982, p. 209 and Ghost, p. 123; “Partial Log As Kept By Survivors, USS Houston,” enclosure (a)(9), 9 September 1945 (found at Hyperwar: World War II on the Worldwide Web (“Hyperwar”): http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/.

Note that nothing in this article should be interpreted as criticism of the survivors of the Houston, who had to endure three years of brutal treatment in Japanese POW camps before they could be interviewed by Allied authorities.

[4]. H.M.L. Waller, Capt., RAN, “Action Narrative B Day and Night Action off Surabaya, February 27, 1942,” in McKie, p. 139.

[5]. Also spelled “Surabaja,” “Soeurabaya,” “Soerabaya” or somesuch.

[6]. Look, for the last time it’s pronounced “CHIL-a-chap,” OK?

[7]. Such casualties included, in no particular order:

1. light cruiser USS Boise struck an uncharted reef in the Sape Strait and was lost to a planned ABDA counterlanding operation off Balikpapan;

2. light cruiser USS Marblehead blew out an engine and was lost to the same ABDA counterattack off Balikpapan;

3. destroyer USS Whipple collided with De Ruyter in a fog;

4. destroyer USS Edsall dropped a depth charge at too slow a speed and it detonated under her stern;

5. destroyer Hr. Ms. Van Ghent ran aground in the Stolze Strait and had to be scuttled;

6. destroyer Hr. Ms. Kortenaer lost rudder control and ran aground off Tjilatjap and was thus lost to the ABDA counterattack off Bali;

7. destroyer USS Stewart rolled over in drydock in Soerabaja and was scuttled (ineffectually, as it turned out, as the Japanese were able to salvage her);

8. destroyer USS Pope developed a leak in the feed pipes to her boilers and was unavailable for the action in the Java Sea;

9. destroyer Hr. Ms. Witte de With had one of her own depth charges detonate under her stern; and

10. destroyer HMS Jupiter was sunk after she apparently struck a discarded Dutch mine.

[8]. See, e.g., Duane Schultz, The Last Battle Station: the Saga of the USS Houston, New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1985, pp. 109, 117-118.

[9]. Doorman has been subject to severe criticism for his performance in the Netherlands East Indies campaign. Morison obliquely criticized Doorman’s caution. Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 3: The Rising Sun in the Pacific, Edison, NJ; Castle, 1948, pp. 310, 311, 340. Morison also notes specifically that the US officers lacked confidence in Doorman. Id., p. 338. John Prados called Doorman “aggressive to the point of recklessness.” John Prados, Combined Fleet Decoded, Annapolis, Naval Institute Press, 1995, p. 255. Edwin Hoyt notes that Doorman was criticized as “misguided and stubborn.” Hoyt, p. 258. Mike Coppock has probably been the most brutal:

| As he yelled "Follow me!" in one of the most desperate and ill[-]conceived sea battles in modem times, an ad hoc fleet of Allied warships was unnecessarily squandered in a do-or-die encounter that became the Armageddon of ego-driven Dutch Admiral Karel Doorman. (Mike Coppock, “The Battle of the Java Sea: A Fleet Wasted,” Sea Classics, Sept. 2007.) |