Banzai Attack on Attu!: US Army Combat Engineers in the Aleutian Campaign

By Del Kostka

Attu rises like a jagged stone from the churning waters of the North Pacific. Barren, wind-swept, and shrouded in perpetual fog, the island has little relevance to a world that is barely aware of its existence. Yet in 1943, this obscure wilderness was the scene of an epic battle between resilient Japanese occupiers and an American invasion force who were equally determined to possess the island. It was a battle fought as much against the elements as with an enemy, and where a small and ill-equipped band of US Army combat engineers found themselves squarely in the path of one of the largest Japanese Banzai attacks of World War Two.[1]

The Japanese seized Attu on June 7th, 1942.[2] The attack was part of a diversionary operation for the Midway campaign that included the carrier-based bombing of Dutch Harbor and the occupation of Attu and Kiska, the western-most islands in Alaska’s Aleutian chain.[3] The Aleutian outposts were coveted by the Japanese for their unique strategic location. Positioned midway between Japan and the Pacific Northwest, an airstrip in the Aleutians would provide a convenient base of operations from which to stage air reconnaissance missions to patrol the northern perimeter of Japan's territorial expansion.[4] The Japanese occupation force, under the command of Col. Yasuyo Yamasaki, included 2650 soldiers of the 303rd Independent Infantry Battalion who spent the majority of their time trying to scratch a landing strip from the frozen, rocky soil along the northeast shore of Attu.[5]

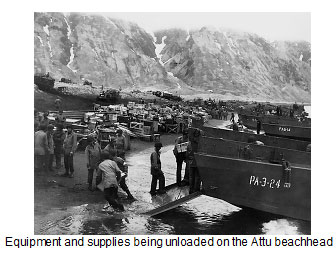

To counter the Japanese occupation, the US Army planned an amphibious assault of Attu for the spring of 1943. The task was assigned to the Army’s 7th Division under the overall command of Major General Albert E. Brown. Brown’s plan was to make simultaneous landings on the northern and easternmost shores of Attu, then push inland in perpendicular thrusts to effectively trap the Japanese on the northeast corner of the island.[6] Brown’s 16,000-strong assault force included three regiments of infantry, four battalions of artillery, and the 7th Division’s own 13th Combat Engineer Battalion. The 50th Combat Engineer Battalion was also assigned to the 7th Division to effect the landing and movement of supplies inland from the beaches.[7]

The 7th Division was not experienced at conducting amphibious operations. Prior to the invasion they had limited amphibious training at Ft. Ord, California, but the relatively warm and tranquil waters of Monterey Bay were a poor substitute for the cold, angry waves of the North Pacific.[8] Security was tight in the months prior to the invasion. Only a few senior planners knew where the 7th Division was headed. Most of the assault force was convinced that their ultimate destination was the South Pacific. This opinion was reinforced by the prominent requisitioning of mosquito netting and summer weight uniforms by logisticians who greatly underestimated the hostile Aleutian weather.[9]

The invasion force departed San Francisco on April 24th, 1943. The initial two week voyage to Dutch Harbor was quiet and without incident, but the journey quickly deteriorated when the task force veered west towards the Aleutians. A cold and damp fog seemed to seep into everything, and the convoy pitched relentlessly in the turbulent Bering Sea. Below deck, chilled infantrymen, who had spent their entire lives on dry land, lay on their bunks and perspired as an epidemic of sea sickness swept through the transport vessels. Those who sought fresh air and solitude above deck were driven back by a dangerous film of ice that encrusted railings, hatches and deck plating.[10] Finally, on May 10 the task force arrived off the shores of Attu. The wobbly legged infantry were relieved to man the landing craft and move towards dry land, but the rough sea voyage had served warning that this invasion would not unfold as the strategists had planned.

On paper the invasion of Attu did not appear difficult, but the operation bogged down almost immediately due to the weather, the terrain and a very shrewd Japanese strategy. The American force had prepared for an intense coastal defense by the Japanese occupiers followed by a brief mop-up period once a beachhead had been established. What they found instead were abandoned shores, as the Japanese pulled back from the coast to await the invasion force in the higher, rocky terrain.[11] The unopposed landing was welcome news to American troops already dealing with churning seas and 25 degree temperatures[12], but it did not bode well for an advance to the island interior which now faced murderous mortar and machine gun fire from the higher ridges.

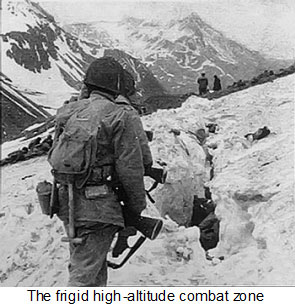

The snow covered peaks surrounding the landing zones tower 3000 ft above the beaches of Attu. Yamasaki deployed his troops in small groups of snipers and mortar teams who used the island’s natural network of caves, crevasses and ridge lines for protection and concealment.[13] Naval and artillery bombardment were ineffective due to the thick fog. The fog also provided an ideal backdrop for Japanese snipers who kept watch on the few accessible slopes to the upper elevations and cut down US infantry as they appeared above the fog line.[14] The guerilla tactics forced the GIs to conduct time consuming and costly search and destroy missions. By May 16th Army Command had grown impatient with the slow pace of operations. Maj. Gen. Brown was relieved of command and replaced by Maj. Gen. Eugene M. Landrum.[15]

The snow covered peaks surrounding the landing zones tower 3000 ft above the beaches of Attu. Yamasaki deployed his troops in small groups of snipers and mortar teams who used the island’s natural network of caves, crevasses and ridge lines for protection and concealment.[13] Naval and artillery bombardment were ineffective due to the thick fog. The fog also provided an ideal backdrop for Japanese snipers who kept watch on the few accessible slopes to the upper elevations and cut down US infantry as they appeared above the fog line.[14] The guerilla tactics forced the GIs to conduct time consuming and costly search and destroy missions. By May 16th Army Command had grown impatient with the slow pace of operations. Maj. Gen. Brown was relieved of command and replaced by Maj. Gen. Eugene M. Landrum.[15]

While the Battle of Attu raged in the hills surrounding the beachhead, the combat engineers set about their logistical task of keeping an army supplied with food, fresh water, medical supplies and ammunition. On Attu the engineers would fight a very personal battle with a tundra ground cover called muskeg, a thick, wet and spongy mat of grass and weeds that blankets the Aleutian lowlands.[16] The task force had brought a small fleet of trucks and caterpillar tractors to construct roads and supply lines, but the heavy vehicles became mired in the muskeg the instant they moved off the pebble covered beach.[17] The muskeg was an enormous and unanticipated obstacle given the necessity to move artillery and supplies to the island's interior.

Realizing the importance of moving the heavy guns and equipment off the beaches, the engineers seized upon a brilliant solution. They proposed using a gravel-bottomed stream that flowed through an interior valley as a roadway. The 13th Engineers improved the creek bed by widening sections and redistributing gravel deposits.[18] Within hours, a steady stream of tractors were towing artillery and ammunition wagons along the improvised supply route. A series of cables were constructed from the stream to the lower ridge lines in order to winch the guns to a suitable emplacement, but the problem of sustaining the infantry in the towering combat zone was another matter. With the terrain too steep and treacherous for motorized vehicles, the engineers would have to move supplies and replenish ammunition using backpacks and pull carts.[19]

Pulling heavy wooden crates up the snow covered slopes was backbreaking work and the engineer's light weight clothing was no match for the cold arctic wind. Frostbite and exhaustion were a constant concern. The grueling climb compelled the engineers to establish a base camp midway along their supply route. A primary supply dump had been placed on the crown of a gradually sloped hill that looked across a low, flat valley.[20] The position also offered an ideal artillery placement from which to shell the Japanese-held high ground that lay hidden beyond the fog covered lowland. The 50th Engineers placed their camp at the very crest of this ridge and designated the position “Engineer Hill,” little realizing the carnage that would soon be associated with the name.

For seventeen long days the 7th Division drove forward with determined pressure to displace the Japanese from their high ground fortress. The Japanese tenaciously defended every ridge and stronghold, but the numbers and elements were against them. As fresh American troops and supplies flowed freely through the open beachhead, the Japanese continued to expend their resources in a futile battle of attrition. By May 28th the Japanese situation had grown critical. Of the remaining 1400 Japanese soldiers, fewer than 800 were in fighting condition. Food, ammunition and medical supplies had grown scarce.[21] In desperation, Col. Yamasaki prepared a bold plan. He would use his entire force to sweep across the valley floor and capture the American artillery position and supply dump at the crest of Engineer Hill. With the artillery, supplies and strategic high ground in Japanese hands, Yamasaki hoped to hold the position until reinforcements arrived by sea.[22]

For seventeen long days the 7th Division drove forward with determined pressure to displace the Japanese from their high ground fortress. The Japanese tenaciously defended every ridge and stronghold, but the numbers and elements were against them. As fresh American troops and supplies flowed freely through the open beachhead, the Japanese continued to expend their resources in a futile battle of attrition. By May 28th the Japanese situation had grown critical. Of the remaining 1400 Japanese soldiers, fewer than 800 were in fighting condition. Food, ammunition and medical supplies had grown scarce.[21] In desperation, Col. Yamasaki prepared a bold plan. He would use his entire force to sweep across the valley floor and capture the American artillery position and supply dump at the crest of Engineer Hill. With the artillery, supplies and strategic high ground in Japanese hands, Yamasaki hoped to hold the position until reinforcements arrived by sea.[22]

On the evening of May 28th, an American reconnaissance patrol crept towards a Japanese encampment to investigate an uncharacteristic noise. As they silently peered over the final ridge, the patrol was astonished to see a large assemblage of Japanese soldiers, many of whom were jumping in place, screaming at the top of their lungs and guzzling bottles of sake.[23] The comical impression soon faded as the patrol realized the enormity of what they were seeing. The frenzied Japanese soldiers were helping their wounded commit ritual suicide, either through morphine injections or self-inflicted gun shots.[24] It was the portent of an abrupt and horrific conclusion to the Battle of Attu.

In the early morning hours of Saturday, May 29th, every Japanese soldier who was still able to walk set off in the dense fog on a silent trek across the valley floor. At 3:15 the Japanese force reached the American front lines and quickly overpowered three sentry outposts. At 3:25 they reached a slight rise in the terrain which indicated the beginning of the half-mile slope to the crest of Engineer Hill. At the base of the hill sat an American rear area and field hospital where several infantry units had assembled for morning breakfast. With a scream of “Banzai” the Japanese horde swarmed out of the fog and easily overran the unprepared American position.[25]

While most of the astonished infantry fled into the fog, the Japanese paused to ransack the clearing station. Central to the rear area were three large hospital tents, each clearly marked with the International Red Cross symbol. The Japanese swept through two of the tents, viciously bayoneting the unarmed medical personnel and wounded Americans as they lay helpless in their bunks.[26] The inhabitants of the third tent managed to survive by lying motionless as the Japanese assembled outside their tent for the ascent of Engineer Hill.[27]

At the crest of the hill, the 50th Engineers woke to the sound of distant gunfire and eerie screams. Most stumbled half-asleep to the edge of the ridge, peered down into the thick fog and listened keenly to the confusing sounds. Suddenly, a terrified infantryman broke out of the fog screaming “the Japs are coming…thousands of em!”[28] The engineers stood for a brief moment in disbelief, then turned and made a furious dash to their tents to gather their M-1’s and helmets. Within moments the engineers had taken shoulder-to-shoulder positions across the crest of the ridge and were staring intently into the 30-foot visibility of the dawn fog.[29] All thoughts of the bone-chilling cold had vanished. There were excited shouts of encouragement and nervous, whispered prayers.

With great discipline the engineers held their fire as still more dazed infantrymen and medics came scrambling to the top of the ridge. Then from deep in the fog came a high-pitched scream, followed by 800 manic Japanese soldiers charging forward with fixed bayonets. The speed of the Japanese attack allowed very little time to accurately select and fix a target. Most of the engineers managed to fire one or two rounds before the Japanese were upon them.[30] Rather than retreat and abandon their critical position, however, the engineers sprang to their feet and met the onrushing Japanese with fists, rifle butts and bayonets.[31] Fueled by adrenaline and the knowledge that they were fighting for their lives, the outnumbered engineers somehow managed to beat back the frenzied attackers. After a brief but savage hand-to-hand melee, the Japanese attack withered and fell back into the fog.

As the shaken engineers gathered their breath, the exhausted Japanese fell back to the captured American field hospital.[32] Any thoughts of pursuing the Japanese were discouraged by the still dense fog that provided a perfect screen for their retreat. After a brief rest and with no other option except unthinkable surrender, Col. Yamasaki led one last desperate charge against the engineer position. This time, knowing the source of the frenzied scream and reinforced by displaced infantry and members of the 13th Engineers who had rushed to join the fray from their base camp on the opposite side of the ridge[33], the engineers opened up with their full firepower before the Japanese ever broke out of the fog. Few Japanese soldiers would reach the crest on this final charge. Col. Yamasaki was killed while waving his sword over his head and urging his men forward.[34]

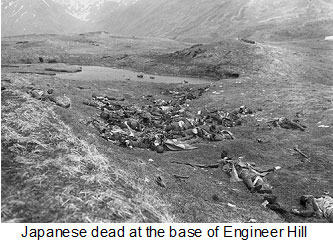

The Japanese survivors staggered back to the base of Engineer Hill. Several small groups made their way back to the caves and rain washes of the high ground, where they were eventually cornered and eliminated by American search teams.[35] Most simply clutched a hand grenade to their chest and scattered themselves across the cold Aleutian tundra. As the fog lifted, the morning sun revealed a grisly sight. Over 500 Japanese bodies lay horribly mutilated at the foot of Engineer Hill.[36] Several hundred more bodies, American and Japanese alike, were littered across the crest and down the long slope of the ridge.[37]

The Japanese survivors staggered back to the base of Engineer Hill. Several small groups made their way back to the caves and rain washes of the high ground, where they were eventually cornered and eliminated by American search teams.[35] Most simply clutched a hand grenade to their chest and scattered themselves across the cold Aleutian tundra. As the fog lifted, the morning sun revealed a grisly sight. Over 500 Japanese bodies lay horribly mutilated at the foot of Engineer Hill.[36] Several hundred more bodies, American and Japanese alike, were littered across the crest and down the long slope of the ridge.[37]

The Battle of Engineer Hill ended the Japanese occupation of Attu, but the price of victory had been very high. Of the approximately 16,000 troops engaged on Attu, the American invasion force suffered 3829 casualties, including 549 killed in action.[38] In proportion to the number of troops engaged, the victory on Attu was second only to Iwo Jima as the most costly American battle of the Second World War.[39] The Japanese cost was higher. Official US records show 2351 dead out of 2378 engaged, although hundreds more are thought to be buried in unmarked graves throughout the desolate hills of Attu.[40]

US Army Combat Engineers played a critical role in the invasion of Attu, facing adversity, hardships and obstacles far beyond the scope of their training. With the fighting on Attu over, the 13th Engineers followed the 7th Division to the South Pacific, where it employed its amphibious assault experience in several more island campaigns.[41] By contrast, the 50th Engineer’s had only begun their battle against the harsh Aleutian elements. The battalion would spend the next seven months in the bitter cold, wind and fog of Attu constructing an airfield and coastal defenses.[42] For their action on Engineer Hill, the 50th Engineer Combat Battalion received the Joint Meritorious Unit Presidential Citation.[43] Alexie Airfield, the 50th Engineers final Aleutian legacy, eventually provided a secure base from which American B-24 and PV-1 bombers launched their devastating raids against northern Japanese possessions and helped eliminate Japanese influence in the North Pacific.[44]

| * * * |

Show Notes

Footnotes

[1]. Von Ribbentrop argued in vain that the Tripartite Pact between Germany, Italy, and Japan stipulated that Germany only needed to go to Japan's aid if Japan were attached, not if Japan attacked another country, which Japan did in attacking the United States military installations at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on December 7, 1941. John Keegan, The Second World War, (New York: Penguin Books, 1990), 240.

[1]. Robert J. Mitchell, The Capture of Attu (Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press, 2000) xviii.

[2]. D. Colt Denfeld, Builders and Fighters, US Army Engineers in World War 2 (US Army Corps of Engineers, 2005) 367.

[3]. Ibid, 367

[4]. Brian Garfield, The Thousand Mile War (Fairbanks: The University of Alaska Press, 1969) 118.

[5]. Ibid., 271

[6]. Mitchell, 6.

[7]. Denfeld, 370.

[8]. Lee F. Bartoletti, Battle of the Aleutian Islands, Recapturing Attu, World War II, http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-the-aleutian-islands-recapturing-attu.htm (Nov 2003).

[9]. Robert E. Burks, Logistics Problems on Attu, Army Logistician, http://www.almc.army.mil/alog/issues/MayJun03/MS778.htm (May-June 2003).

[10]. Donald E. Kostka, Co D. 50th Engineer Combat Battalion, interview by author, Fargo, North Dakota, 23 Dec 2009.

[11]. Garfield, 272

[12]. Ibid, 274.

[13]. “Battle of the Aleutians,” Military Review, Vol 25, April 1945: 32.

[14]. Mitchell, 40.

[15]. Garfield, 305.

[16]. Burks, http://www.almc.army.mil/alog/issues/MayJun03/MS778.htm

[17]. Ibid

[18]. Denfield, 373

[19]. Burks, http://www.almc.army.mil/alog/issues/MayJun03/MS778.htm

[20]. Denfield, 375

[21]. Garfield, 327

[22]. Ibid, 328

[23]. Bartoletti, http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-the-aleutian-islands-recapturing-attu.htm

[24]. Ibid, http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-the-aleutian-islands-recapturing-attu.htm

[25]. Garfield, 329

[26]. William S. Jones, The Battle of Attu, World War Two Chronicles, http://www.americanveteranscenter.org/magazine-test-page/wwii-chron-page-test/wwii-chron-issue-1-page-test/the-battle-of-attu (Issue XXXVIII, Spring 2007)

[27]. Mitchell, 110

[28]. Kostka interview, 23 Dec 2009.

[29]. Kostka interview, 23 Dec 2009.

[30]. Kostka interview, 23 Dec 2009.

[31]. Garfield, 331

[32]. Ibid, 331

[33]. Denfield, 376

[34]. Garfield, 331

[35]. Bartoletti, http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-the-aleutian-islands-recapturing-attu.htm

[36]. Garfield, 332

[37]. Kostka interview, 23 Dec 2009.

[38]. Garfield, 333

[39]. Ibid, 333

[40]. Ibid, 333

[41]. 7th Infantry Division Combat Chronicle, World War Two Archive Foundation, http://wwiiarchives.net/servlet/organization/466/1941

[42]. Kostka interview, 23 Dec 2009.

[43]. Department of the Army Pamplet 672-1, Unit Citation and Campaign Participation Register, HQ Dept of Army, July 1961: 109.

[44]. Ralph Wetterhahn, Fire and Ice, Air and Space Magazine, http://www.airspacemag.com/military-aviation/fire-ice.html?c=y&page=4 (1 March 2006)

| * * * |

© 2026 Del Kostka.

Written by Del C. Kostka.

About the author:

Del C. Kostka is a staff officer at the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency in St. Louis, Missouri. He has a Masters Degree in Operational Arts and Military Science from the US Air Force Air Command and Staff College.

* Views expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily represent those of MilitaryHistoryOnline.com.