The U.S. Army Model 1913 Cavalry Saber

By Bob Seals

|

"Don't cut! The Point! The Point," The U.S. Army Model 1913 Cavalry Saber

"At Wagram, when the cavalry of the guard passed in review before a charge, Napoleon called to them, 'Don't cut! The point! The point'"[1] Second Lieutenant George S. Patton, Jr. 1913 |

Introduction

For some 159 years, United States Army used an edged sword, the saber, as the primary weapon for mounted troops. Whether called light horse, dragoon, or cavalry, the Army cavalry trooper on horseback carried a saber, with which to engage the various foes of our republic. The last issued Army saber in a long line, the model 1913 saber, became popularly known as "The Patton Saber," after then Second Lieutenant George S. Patton, Jr., who it is commonly believed was somehow responsible for the design and adoption of the new saber, during that very same year. Over the years, some authors, and historians, have questioned the veracity of conventional historical wisdom in naming the model 1913 saber "The Patton Saber," since, after all, how much influence could a lowly Second Lieutenant have had in the U.S. Army's procurement of a new weapon?[2]

The purpose of this article is to introduce the reader to the U.S. Army model 1913 saber, and examine the facts surrounding the adoption of this last saber issued to Army troopers from before the First World War, until its subsequent withdraw as a modern weapon in the interwar year of 1934. A review of the historical record, and timeline, surrounding the saber, does indicate that Second Lieutenant George S. Patton, Jr. was indeed responsible for the Army's adoption of the saber, displaying those considerable powers of single mindedness, will, dedication, and zeal that made him such an effective maneuver combat general three decades later in North Africa and Europe. Patton's thinking, study, experimentation, and advocacy of this new edged weapon were indicative of his professional development as a military leader. This professional development was to ultimately lead the young, but talented officer, to recognize the value of the armored tank replacing a shiny saber as the weapon of choice for a modern mounted Army.

Background

George Smith Patton, Jr. was born on the 11th of November 1885 on his family's prosperous cattle ranch near San Gabriel, California. His childhood out west was a rather idyllic one in Southern California with loving parents, a sister, dogs, horses to ride, fish to catch, birds and wild goats to hunt, and history to read. As a child, surrounded by mementos of his paternal grandfather's service with the 22nd Virginia Infantry, Patton had a fondness for toy swords. His father used a Civil War Confederate sword to play with young George "...kneel[ing] down and we would fight." Later, Patton's father bought him his first sword, "...A store in Los Angeles was having a sale of 1870 French Sword bayonets and I asked for one...later I attacked the cactus with it and got well stuck..."[3]

This edged weapon enthusiasm extended into his college years at the Virginia Military Institute and the United States Military Academy at West Point. A versatile and gifted athlete, by the standards of the day, Patton pursued several sports with gusto, at West Point, to include football, polo, and track and field, to include earning his varsity letter A for breaking a school record in the 220 yard hurdles. Additionally, Patton was an enthusiastic fencer. As a cadet he competed with the broadsword against a visiting New York City German fencing club, registering ten touches against an opponent while receiving only two in return. Proudly writing his future wife Beatrice in March of 1908 of his feat, Patton stated "...pardon my boasting but...I would so like to be good with the sword."[4] Graduating 46th out of 103 graduates in the class of 1909, Patton choose the Army branch still using the saber, the cavalry. Assigned to the 15th Cavalry Regiment at Fort Sheridan, Illinois, Second Lieutenant George S. Patton Jr. was to get his chance to become better with the sword.[5]

Adoption of the M1913

The next several years found Patton assigned to K Troop, 15th Cavalry, at Sheridan, engaged in normal duties and responsibilities as a new lieutenant. These included getting married, fathering a daughter, learning to use a typewriter, and discovering that he enjoyed writing and producing short military papers. His writing was rather noteworthy for a junior officer. As noted historian Martin Blumenson has written, the process was more important than the actual product, as Lieutenant Patton taught himself how to organize material, think critically and challenge accepted doctrine or tactics of the day.[6] These abilities are clearly seen in the development and adoption of the model 1913 cavalry saber.

In 1911 the U.S. Army convened a board of cavalry officers to examine new equipment and make recommendations. One of the items of cavalry equipment the board recommended changing was the model 1906 saber. An experimental model 1911 saber under study was to retain the traditional Army curved single edged blade, similar to those carried since the Civil War era. But the model 1911 was never to be adopted, due to Patton's advocacy of a straight, double edged cavalry saber, ultimately gaining his name. That same year, late in 1911 Lieutenant and Mrs. Patton were transferred to the showplace of Army cavalry of the day, Fort Myer. Assigned to A Troop, 15th Cavalry, Patton was close to the powerful and influential Army officers and governmental officials in Washington, D.C., and made the most of this opportunity.[7]

Early in 1912 Patton was assigned duties as squadron quartermaster, but was informed in March that he was under consideration to be the Army's representative in the Modern Pentathlon at the Fifth Olympic Games the upcoming summer in Stockholm, Sweden. Consisting of five events; the pistol, swimming, fencing, riding, and running, the pentathlon was, in effect, a test of military skills a soldier might encounter on the battlefield. Informed in May he had been selected, Patton began intensive training in the five disciplines and dieting. Brushing up on his sword skills, he fenced three times weekly and competed in the National Championship fencing tournament held that spring in New York. Additionally, during the sea voyage to Sweden, on the ship Finland, Patton fenced for two hours daily. Competition began on 7 July with Lieutenant Patton performing well in all five events. Two days later the fencing portion of the pentathlon was held at the Royal Tennis Courts. Armed with the dueling sword, Patton performed admirably, finishing third of the remaining 29 competitors, and proudly wrote later "I was fortunate enough to give the French victor the only defeat he had," during the two days of intense fencing competition.[8]

Finishing fifth in the pentathlon, his standing was 6th in swimming, 3rd in fencing, 3rd in riding, 3rd in running, but his pistol score of 21st place knocked Patton out of the medals. All in all it was a remarkable performance for the young Lieutenant, made more enjoyable by the presence of his wife, sister, and parents, who witnessed those 1912 Olympics that made the name of great athlete Jim Thorpe a household word. While in Sweden Patton had a chance to meet many of the finest swordsmen in the world, who informed him that a French army cavalry officer was considered the best in Europe. This officer was Adjutant Clery, the Master of Arms and fencing instructor at Saumur, the French Army's cavalry and equestrian center in western France. Champion of the continent in foil, dueling sword and saber, Clery was the acknowledged master of the edged weapon and a man Patton had to meet, and possibly learn from, before returning to the states.[9] While his parents and sister toured Europe, Patton and Beatrice traveled to Saumur, for private lessons from Clery in the dueling sword and saber disciplines, during that last half of July.

The experience was to be life changing. Lieutenant Patton took full advantage of the opportunity at Saumur with Adjutant Clery; not only improving his sword skills, but also his thinking about military training, instruction, and the nature of the European and American saber of the day. The French Army, and Adjutant Clery, stressed the advantage of a straight, powerful, aggressive thrust in a mounted or dismounted attack with the saber, vice a slashing assault with the weapon's edge, such as favored by the U.S. cavalry. Patton was impressed by what he saw, and became convinced of the superiority of a straight blade on a saber, as opposed to a curved, single edged blade saber, such as the model 1906 or experimental model 1911 U.S. Army Cavalry saber under consideration. In his report that fall later to the Army's Adjutant General, Lieutenant Patton listed five advantages of a straight saber, summarizing that "For these reasons the French, English...Swedes and I believe most other nations are adopting straight swords or sabers."[10] In the months ahead Patton fought hard to convince the U.S. Army of this superiority.

Returning to Fort Myer, Lieutenant Patton plunged back into his duties with the 15th Cavalry. His commanding officer of the regiment, Colonel Joseph Garrard, USMA class of 1873, was impressed with Patton's report from Saumur, and encouraged him to publish it in the Cavalry Journal. Patton wrote his wife of his intention to do so, and added "They [Army] are almost certain to adopt my sword blade as the new regulation [saber] so I may get some prominence yet, I hope so."[11] Perhaps due to his noteworthy Olympic performance, or well received writing, in December of 1912 Patton was selected for detached service for duty with the Army's Office of the Chief of Staff. This was significant, even for a Second Lieutenant such as Patton, with an automobile and chauffeur, who did not have to depend upon his Army salary of 170 dollars a month. Lieutenant's Patton's duties brought him into close contact with both Major General Leonard Wood, the Army Chief of Staff, and Henry L. Stimson, the Secretary of War. Patton's analytical writing and typewriting skills came in handy as he prepared various staff papers for both, to include a study on the benefits of polo play for Army officers.[12]

In the New Year, the Army and Navy Journal, the most influential U.S. defense journal at the time, published an article on 11 January 1913, entitled "Use of the Point in Sword Play," citing a lengthy discussion upon the virtues of a straight pointed saber with an unnamed officer at the War Department, who was, without a doubt, Patton.[13] Additionally, in a superb display of showmanship during his short tenure, Lieutenant Patton displayed at the Chief of Staff's Headquarters, a French sword, used in the Battle of Waterloo, that he had purchased in Paris, presumably supporting his straight edged saber advocacy. The Lieutenant had General Wood's ear, writing the Military Academy to inquire on behalf of the Chief in reference to the upcoming Intercollegiate Fencing Tournament, mentioning that the General was thinking of adopting a straight edged saber for Army cavalry.[14] More than just thinking, Wood allowed Patton to travel to the venerable Springfield Armory in Massachusetts on 18 February 1913 to confer with officers and officials there reference the new Army saber, and produce a sample.[15]

Six day later, on 24 February 1913 General Wood signed a memorandum sent to the Chief of Ordnance ordering the production of 20,000 new U.S. Army Cavalry sabers, with a straight double edged blade, according to a design example specified by Patton. Lieutenant Patton, the following week, rode in the Wilson Inaugural Parade as an aide to General Wood. Patton had done very well during his short three month tour. So well, in fact, that the Chief of Staff presented him with a letter of appreciation in March on the occasion of Patton's release from his temporary staff duty. In that day, before our current extensive Army system of awards and decorations, such a letter was extremely significant. In that same month Patton was sent on temporary duty for three days to the Springfield Armory in Massachusetts "...to approve the new sword." A second letter in April was entered into Patton's record after this short duty at the armory by the Acting Chief of Ordnance to express appreciation for his skill and assistance in regards to the new Army saber.[16] It seems clear that Patton was indeed instrumental in the model 1913 saber coming into being.

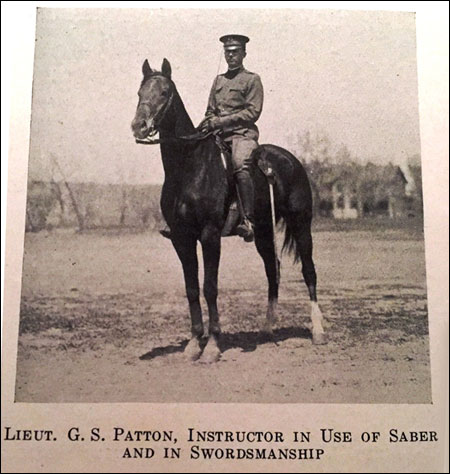

Lieutenant Patton had "The Form and Use of the Saber" accepted for publication in the March 1913 edition of the Cavalry Journal, the first of some 16 articles he wrote for this professional journal during the next 30 years.[17] A summary of his learning from the French cavalry school and Adjutant Clery, the article was a forceful argument again for the straight saber and French tactics and training. But Patton was not finished yet. He had discussed and proposed with all who would listen the idea of introducing a course in swordsmanship at Fort Riley, the home of the cavalry. Accordingly in June orders from the Secretary of War arrived for Patton stating the War Department "...authorizes you to proceed to France [at no cost to the government] for the purpose of perfecting yourself in swordsmanship...[and] arrive at Fort Riley, Kansas by October 1." [18] The Mounted Service School at Riley had approved a new position of Master of the Sword, who was to conduct a six-month course of instruction for a selected NCO from each cavalry regiment later in the year. Lieutenant Patton was off to Saumur again, for additional training, enroute to becoming the first U.S. Army Master of the Sword.

Arriving back at the now familiar Hotel Budan in July with his wife, Patton had less than two months to perfect his saber skills with Adjutant Chef Clery, who had been promoted. He worked hard to perfect his French, and improve his teaching and fencing skills, ably assisted by wife Beatrice, who with her superior level of French, translated lectures and manuals for Patton. The time passed quickly. At the end, Clery presented Lieutenant Patton on his last day with an inscribed photo of himself in fencing uniform, entitled "to my best pupil, le Lieutenant Patton."[19] Back in the United States, production of the U.S. Army model 1913 cavalry saber had begun. Lieutenant Patton reported to Fort Riley towards the end of September in 1913 to prepare his course and begin duties as the first U.S. Army Master of the Sword.

The Saber Itself

The historic Springfield Armory, located in Springfield, Massachusetts, that had produced U.S. military firearms since 1777, now produced the last Army cavalry saber. The model 1913 saber, with a doubled-edged blade made of forged steel, had a sheet metal hand guard and hard black rubber grips, and was 41.5 inches in length, with a 1.175 inch wide blade that was 35.25 inches long. A leather washer was at the base of the blade to protect the guard when in the scabbard. The scabbard itself was constructed of treated hickory wood, covered in rawhide and khaki drab canvas, with a tip and mouthpiece of steel with two rings for attachment to the saddle. A leather saber knot was attached to the handle of the saber, and enabled the trooper keep his saber if the weapon was knocked from the hand.

Rather unglamorously, the original scabbard for the saber produced had a metal tip at the end which enabled the scabbard to be used as a shelter-tent pole in the field by a cavalry trooper. The overall weight of the saber with scabbard was 4.5 pounds. Springfield Armory produced over 35,000 of the model 1913 sabers for the next five years until 1918. Sabers manufactured at the armory were marked with the initials SA, a flaming bomb Ordnance insignia, date and serial number on the blade. An additional 93,000 sabers were contracted after the U.S. entry into the First World War in 1917, and manufactured by Landers, Frary and Clark. These models have no serial numbers but were marked with LF & C, and the dates of either 1918 or 1919.[20]

Aftermath

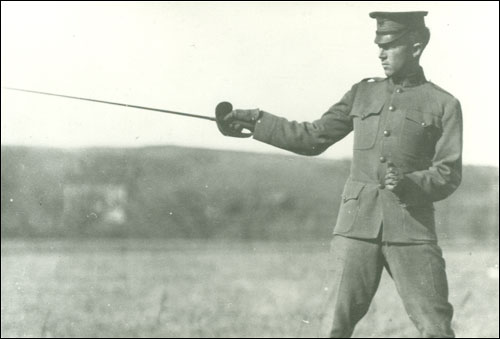

Now that his saber was a reality, Patton continued to defend and promote its use in the years to come. It helped to be the first U.S. Army Master of the Sword. In 1914, in response to a request from the Cavalry Board, Lieutenant Patton proposed a test, and standards, that were adopted for the new Army swordsman's badge. This rectangular metal badge, which depicted the new model 1913 saber superimposed over the word SWORDSMAN, was awarded for proficiency with the new saber during a mounted timed and scored designated course, while engaging 10 dummies and successfully jumping a 5 foot hurdle. Only awarded to enlisted, the badge was awarded annually to the best two enlisted soldiers in each cavalry troop, as a highly prized emblem of distinction.[21] That same year Patton graduated from the Mounted Service School at Riley and wrote the Army Saber Exercise manual to help spread the M1913 gospel.[22] Patton also in the 1914 Rasp, the Mounted Service School’s annual yearbook, penned an article entitled “Mounted Swordsmanship,” describing the new model sword as “…an ideal thrusting weapon.”[23]

In 1915 Patton made arrangements to be assigned to the 8th Cavalry Regiment at Fort Bliss in Texas, anticipating further troubles along the border with Mexico. After Thanksgiving that fall, Patton’s troop was alerted and moved to the Rio Grande to intercept Mexican bandits. For Patton this was a perfect opportunity to lead a glorious saber charge, “I thought I had my medal of honor sewed up and laid awake planning my report;” however, the bandits slipped back over the border, frustrating his plans. Patton was more successfully attracting the notice of the post’s commanding general, John J. Pershing, who was to choose the young lieutenant as an Aide during the Punitive Expedition into Mexico, no doubt somewhat influenced by his romantic interest in Patton’s single older sister, Nita. Before leaving Fort Bliss with the expedition force in 1916 Patton watched a parade of mounted cavalry carrying the M1913 saber and wrote “My eyes filled with tears…The nearest similar feeling I can remember is on the occasion of certain very noise Opera music.”[24]

Patton's writings continued to include several Cavalry Journal articles; a July 1916 article "Defense of the Saber;" a January 1917 article "Cavalry Work of the Punitive Expedition;" and the April 1917 article "Present Saber: Its Form and Use for Which It Was Designed." Promoted, at last, after seven years of service to First Lieutenant in 1916, Patton continued to argue that "...expert use of the pistol or saber are demanded for successful mounted attack," and "In the charge, the point will always beat the edge." Interestingly enough, Patton modestly wrote reference the 1914 saber manual that "If I were to claim any originality in the manual, this statement would be presumptuous. I do not; it is an almost verbatim copy of the new French manual..."[25] Receiving a check for the princely sum of $2.50 for one of his articles, Patton returned the money writing his wife that “I returned the check as I will not take money for defending the saber. It would be sacrelidge (sic).”[26]

By now widely considered as the Army’s saber expert, the Cavalry Board wrote Patton in March of 1916 to ask his opinion of proposed changes to the M1913 saber, to include changing the form back to a curved model. He was violently opposed to such a concept in a six page single spaced response back to the board.[27]

Patton, and two Provisional Cavalry Brigades, served in Mexico during the 1916 Punitive Expedition with General Pershing, but no there is no record of the M1913 being used during those operations. The following year, in 1917 the U.S. entered the First World War. Four Army cavalry regiments served in France during the First World War, with one mounted regiment, the second, seeing combat in the waning days of the conflict; however, again there is no documented use of the saber.[28]

The "Roaring Twenties" soon became the grim thirties, and it was during those terrible depression years, ironically, that Patton participated in the only known U.S. Army incident where the M1913 saber was to be used in anger. Back at Fort Myer again, on the eighth day of July 1932, now Major Patton reported for duty as the executive officer of the 3rd Cavalry Regiment. Twenty days later, after the District of Columbia believed it had lost order and requested federal troops, Patton, 13 officers and 217 enlisted men from the 3rd Cavalry deployed along Pennsylvania Avenue to help disburse the so-called Bonus Army. These demonstrators, composed of World War Veterans, were protesting in Washington DC at the time, to demand their congressionally authorized bonus payments.

Writing afterwards Patton commented "The soldiers were magnificent. They set grimly on their horses and made no reply...Bricks flew, sabers rose and fell with a comforting smack, and the mob ran." No veterans were killed in the incident, and the M1913 saber appears to have been used as a flat edged crowd control tool in order to move Bonus protestors along. Major Patton also made a point to praise the disciple of all troops involved writing that "It speaks volumes for the high character of the men that not a shot was fired."[29] This unfortunate and controversial incident was only two years before the saber was finally withdrawn from Army cavalry service in 1934, after some 21 years of faithful use. An era in Army history had come to a close.

But what did not come to a close was Patton's interest in sabers, with or without the M1913. In the spring of 1938, while stationed at Fort Riley, he sent three sample saber models to the new Chief of Cavalry, Major General John K. Herr, for inspection and consideration. Patton also discussed the benefits of a bayonet being issued vice a full sized saber. Perhaps one of the samples was a sword bayonet similar to his first purchased by his father many years before. In any event Major General Herr was instrumental in Patton's continued success, with the last Chief having the Army Adjutant General promote Patton to full colonel so he could subsequently command the still horse mounted 5th Cavalry Regiment at Fort Clark in Texas, and back to Fort Myer to command the 3rd Cavalry Regiment. Regimental command was to be a key step towards Patton afterwards becoming a general officer in the waning years before the Second World War.[30]

Patton, as late as the fall of 1939, after the 3rd Cavalry’s participation in the First Army Maneuvers at Manassas in Virginia continued to advocate saber use writing in the Cavalry Journal that “Time and again in these exercises the vital necessity of providing cavalry with sabers was demonstrated because in close terrain cavalry can and did…approach unobserved..[and] make a mounted charge with ‘cold steel’…securing a decisive result with a minimum loss of time and personnel.”[31]

By 1942, the Army’s cavalry branch, with or without the saber, was effectively finished. Horse mounted regiments traded in their equine mounts for tanks, personnel carriers, and jeeps as the United States Army prepared for a global war against the Axis powers. The mission of the cavalry had not changed much, as units with “steeds of steel” continued to perform the doctrinal missions of reconnaissance, counter-reconnaissance, screening, and pursuit when called upon by the Army. The Army’s largest mounted cavalry organization, the 1st Cavalry Division, fought in the Pacific, the first unit into the capital cities of Manila and Tokyo.

The Second World War gave the M1913 saber a new lease on life, but not for the mounted service Lieutenant Patton had foreseen years before. The U.S. Government, possessing large numbers of such high quality swords in storage, cut many up in order to make fighting knifes for the Army and Office of Strategic Services (OSS) operators engaged overseas in Africa, Asia and Europe. Thus, troopers in the war did carry, to an extent, Patton knifes vice sabers, during combat in the war. This was a rather fitting end for thousands of Patton sabers, which like their superb advocate, served their nation right to the fighting’s end in 1945. Today, the M1913 Patton saber, and scabbard, are prized military antiques, and as such are eagerly sought by collectors with a brisk business online and at many trade shows.[32]

Conclusion

This article has introduced all to the last issue saber used by the U.S. Army cavalry, the M1913 Patton saber. As we have seen, Second Lieutenant George S. Patton, Jr. was indeed responsible for the Army's adoption of this straight edged saber, vice the experimental curved M1911 model, as he displayed the characteristic single mindedness and driving force that were to make him such a household word during the Second World War.

Additionally, Patton displayed a considerable amount of professional acumen and intellectual curiosity as a lowly Second Lieutenant with his advocacy of this new edged weapon. He certainly influenced the Army, and wrote history, by becoming the first ever Master of the Sword, instructing, writing, and promoting the manly virtues of an aggressive, pointed thrust towards a potential enemy. Never wavering, to an extent, in his saber beliefs, he continued to believe that “Truly, a saberless cavalry…would be like a body without a soul.”[33]

Eventually, Patton did get a chance to use his namesake saber, but not under the conditions that he, or anyone else, could have foreseen in 1913 before the start of the First World War. In the end the M1913 Model saber should truly be remembered as the Patton saber, to honor the remarkable man, and many thousands of other cavalry troopers, who honorably rode "Forty miles a day on Beans and Hay," as the famous barracks ballad proclaimed, with a U.S. Army saber by their side.[34]

| * * * |

Show Notes

| * * * |

© 2026 Bob Seals

Written by Bob Seals.

About the author:

Bob Seals is a retired Army Special Forces officer currently working at the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School on Fort Bragg. He lives on a small horse farm with his wife, a retired Army Veterinary Corps officer. He was fortunate to have served with several Son Tay Raiders during his career.

* Views expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily represent those of MilitaryHistoryOnline.com.