"Forgotten Master": T.E. Lawrence and Asymmetric Warfare

By Evan Pilling

There have been few leaders in military history that have caught the popular imagination more than T.E. Lawrence, or "Lawrence of Arabia." Books, movies, and recollections of this enigmatic figure have served to cloud the reality of the man and surround him with exaggerations and legends. Lawrence, an odd and eccentric figure by any measure, himself did much to add to the air of mystery about his leadership ability and what he actually accomplished during the First World War. These uncertainties aside, what Lawrence did accomplish while serving as British liaison to the Arab forces involved in the Arab Revolt (1916-18) against the Ottoman Turks was to conduct an effective military campaign that is a dramatic example of asymmetric warfare, one form of which is guerrilla or irregular warfare. He used his cultural understanding of the Arabs and knowledge of the region, along with significant leadership skills, to guide the Arabs in the conduct of an irregular campaign. Although at best a sideshow in the overall conduct of the First World War, the operations that Lawrence led produced effects disproportionate to the number of irregular troops that participated and served as a supporting operation to the ultimate British victory in Palestine. Lawrence's campaign demonstrated the potential effectiveness of irregular forces against conventional troops and the difficulties that conventional armies face in combating these forces.

In addition to his famous deeds, Lawrence wrote extensively after the war and clearly expressed his philosophy of irregular warfare. While Lawrence is not as well known as some of the great military philosophers, he did leave a written legacy that influenced future military writers and generals. The principles of irregular warfare that he articulated are still relevant today in the ongoing conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Lawrence's successful waging of asymmetric warfare and his views on the requirements for successful asymmetric operations make him worthy of a look as a "Forgotten Master."

Lawrence and his Irregular Campaign

Lawrence was serving as a British military intelligence officer in Cairo in 1916 when he was assigned to the Arab Bureau of the British Foreign Office. The Arab Bureau was tasked with organizing and coordinating the sporadic Arab Revolt against the Turks that had been ongoing for several years. The intent was that the Arab irregular forces would operate in support of General Allenby's conventional military operations in Egypt and Palestine that focused on defending the Suez Canal and eventually pushing the Turks out of Palestine and capturing Damascus. Lawrence, who had extensive experience in the Middle East, became the British political advisor to the overall Arab field commander, Feisal, as well as serving as an active commander of Arab forces himself. His personal relationship with Feisal gave Lawrence significant influence and was the main reason that he was given the freedom to develop and execute the irregular strategy that was to follow.[1]

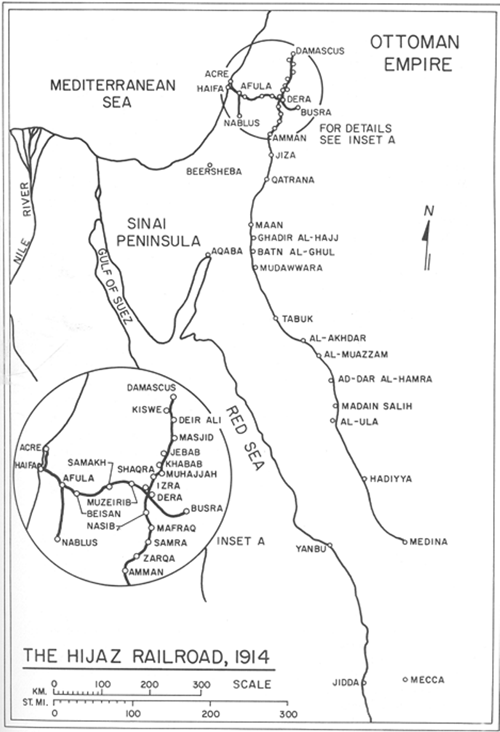

Lawrence convinced Feisal that his irregular troops should not engage the Turks in fixed battles as they had been attempting. Feisal thought that, in order to defeat modern armies, he had to fight them in conventional style. Lawrence immediately perceived the folly of these tactics and the fundamental asymmetric nature of the conflict. He convinced Feisal that the Arab irregular forces should instead conduct hit-and-run attacks and raids using small, independent, mobile groups of fighters. Lawrence realized that this style of warfare was in keeping with the traditional Arab way of fighting: emphasis on the individual fighter over the unit, loyalty toward family and tribe before army, and a disinclination to accept high casualties -- there was no shame in retreating to fight another day.[2] Lawrence's strategic vision of his campaign was to threaten the important Hejaz railway, which ran 800 miles from Damascus into the Arabian Peninsula and was the key Turkish supply route in the region (Map 1). A credible threat from the Arab irregular forces would force the Turks to extend their flanks through the entire length of the railway in order to provide security and require that their forces to be dispersed thinly to accomplish this. This had the potential to severely reduce the Turkish advantages of massed troops and heavy firepower while maximizing the Arab strengths of speed, mobility, and expert knowledge of the desert environment.[3]

Map 1 Source: http://nabataea.net/Hejazmap2.html |

Lawrence began his operations in Arabia with a surprise assault on the coastal town of Weijh in January 1917. The lightly defended town was taken with minimal casualties to the Arabs and this success caused the British authorities in Cairo to realize the potential of the Arab irregulars and to send additional arms, supplies, and money to keep these operations going. It also gave the Arab forces confidence both in themselves and Lawrence's leadership. Lawrence then began a prolonged assault, consisting of repeated small-unit attacks, on the section of the Hejaz railway between Medina and Damascus with the intent of neutralizing the Turkish forces garrisoned there. His forces would appear on camel, with no warning, strike, and then retire back into the desert where they could not be pursued. They required few supplies and the speed and endurance of their camels gave them the ability to move rapidly without detection, often between fifty and one hundred miles a day. Lawrence did not want to destroy the railway or the Turkish garrisons. His aim was to force the Turks to spend increasingly scarce resources on guarding the track, continually making repairs to destroyed sections of railway, and supplying the large number of troops spread along the route and garrisoned in Medina with food, water, weapons, and equipment. These troops would be unable to advance to Mecca or retreat to Damascus. They would be rendered immobile, of little use against the Arab forces but unable to be employed in other areas. Through his strong leadership abilities and utilizing deep cultural knowledge, Lawrence coordinated the operations of seven different and independent Arab tribes against the Hejaz railway and launched often-simultaneous multiple attacks at different places with little or no warning.[4] In response to the Arab attacks, the Turks had to deploy approximately 16,000 men in Medina, another 6,000 along the key link between Medina and Maan, and a further 7,000 men to guard Maan itself. These troops were not fighting -- they were essentially a wasted force that was an increasing logistical drain to the Turks. The most strategically important operation of Lawrence's campaign was the dramatic surprise capture in July 1917 of the key port of Aqaba. This was also a more conventional type of attack, but good intelligence, the element of surprise, and a small Turkish garrison, allowed the Arab forces to succeed. The seizure of Aqaba allowed direct contact between the Arab forces and the British forces in Suez and enabled more rapid and effective communication and resupply. Aqaba became a base from which the Arab forces could operate in direct support of Allenby and target the stretch of railway lines running north to Damascus. The Arab attacks continued on the Turkish railway lines until the end of the war, tying down large numbers of Turkish troops that would have been more effective if employed elsewhere. Lawrence's mobile troops captured the key town of Deera and then joined General Darrow's British Camel Corps for the conventional final assault on Damascus in October 1918.[5]

The overall impact of Lawrence's small force of irregulars was significant. During the period of 1917-18, the Arab forces destroyed 79 railway bridges and hundreds of miles of railway. The Turks had to constantly make repairs while knowing that other attacks would come elsewhere along the line. Although playing only a supporting role to the main British offensive, the 3,000-man Arab force compelled the Turks to keep 50,000 troops east of Jordan to protect the Turkish flank. Another 150,000 Turkish troops were deployed in unsuccessful attempts to locate and destroy the Arab forces. When the conventional British forces under Allenby made their final assault on Damascus, only about 50,000 Turkish troops remained to oppose him.[6] Although Lawrence did not often seek direct combat with Turkish forces (indeed, he sought to avoid it), the Arab forces killed approximately 35,000 Turks by war's end and captured or wounded a similar number. By wars end, the Arab forces exercised de facto control of over 100,000 square miles of territory.[7] Although Great Power realpolitik among the victorious allied nations prevented the creation of an Arab state, the dramatically asymmetric results achieved by Lawrence's small and lightly armed force demonstrated the potential strategic effectiveness of an irregular campaign against a conventional army, given the right circumstances and enough time. After the war, Lawrence wrote his philosophy of irregular warfare and explained what factors had contributed to the Arabs' success.

Elements of Irregular Warfare

Lawrence was highly educated and well versed in the principles of Clausewitz. The idea of overwhelming force at the decisive point, a battle of annihilation, was well known to him. In the Middle East, however, Lawrence saw that the traditional notions of conventional battle were inadequate. He came to the conclusion that his original belief that irregular warfare was just another form of Clausewitzian warfare was incorrect. Lawrence thought a great deal about irregular warfare during the war and ultimately developed his own philosophy of this type of warfare. Lawrence articulated his own "trinity," although it was not as thorough and detailed as Clausewitz's version. He postulated that irregular warfare was composed of three "elements" that he labeled "algebraical," "biological," and "psychological."[8]

Lawrence saw the algebraic element as that part of warfare that was technical and mathematical in nature. It included factors such as space and time, terrain, weapons, lines of communication, and fortresses, to name a few. Lawrence applied this element in the Arab Revolt by calculating that the Turks would require more than six times as many troops as they had available to control the Arab territory through which the Hejaz railway ran. The Arabs would utilize the immense space of the desert to maneuver against key targets over a long period of time. Time was seen as a weapon to use against the enemy, wearing down their will and sapping their strength. The Turkish troops would not be able to achieve a decisive battle of annihilation over the Arab forces. Lawrence rightly assumed that he would have the initiative and that the Turks' superior numbers and firepower would be irrelevant given the massive area of ground that they had to attempt to control and their inability to bring the Arabs to battle.[9]

The biological element applied to the human factor in warfare. Lawrence thought that 90 percent of tactics was certain and could be taught; the other "irrational" part was the true test of generals, a view similar to Clausewitz's concept of "genius."[10] Effective leaders had to have an instinct for the right method to use against the best point of attack. The biological element also dealt with relative troop strengths. Lawrence saw that the Turks could afford to lose troops, but not equipment along a long supply line; the Arabs, on the other hand, could afford very few losses in men. This confirmed his view that sudden, hit-and-run strikes against supplies and lines of communication were essential, rather than direct battle against superior troop strength. The Arab forces only needed to wear down the Turkish army, not annihilate it. Surprise, based on accurate intelligence to avoid engaging superior forces, was paramount in this type of warfare. Lawrence wanted nothing left to chance and said, about his intelligence efforts, "We took more pains in this service than any other staff I saw."[11]

The third element of irregular warfare was the psychological factor that dealt with the mind and will of both the combatant forces and the civilian population of all countries involved. This is also similar to the "people" part of Clausewitz's trinity of warfare. Lawrence viewed propaganda, or information operations, as essential in irregular warfare. He saw the printing press as a key weapon of warfare and a means of positively affecting friendly morale while attempting to demoralize the enemy. Lawrence felt that the Arab troops had to have the idea that they were fighting to eject a foreign power and to obtain an independent homeland (a goal not shared by the European allies). This belief gave them the ability to endure the losses and privations of the war and provided a psychological advantage over the Turks, who felt increasingly isolated and demoralized, and was a key factor in the success of the irregular campaign.[12]

These three elements of warfare shaped Lawrence's view of asymmetric strategy. He realized that his troops were incapable of defending positions against larger conventional forces or of attacking heavily defended Turk positions. The strategy that Lawrence developed and articulated was to wage a protracted irregular war that would ultimately wear down and exhaust the Turks. Killing Turkish troops was not his main aim. Instead, he saw the destruction of railways, weapons, and supplies as more important. These materiel targets were the enemy's center of gravity, although Lawrence did not use that term.[13] After the war, in his major works Seven Pillars of Wisdom and Anatomy of a Revolt , Lawrence discussed the main principles of his strategy in what he referred to as his "thesis" of irregular warfare. The principles are outlined essentially identically in each work and give a picture of the depth of thought that Lawrence applied in his search for a winning irregular strategy. Although Lawrence was well versed in Clausewitzian theory and the Arab Revolt could be seen as a "people's war," his asymmetric strategy is more akin to Sun Tzu's indirect approach to warfare.

Lawrence's "Thesis" of Irregular Warfare

Lawrence discusses six principles for successful irregular warfare in his "thesis." First, the irregular forces must have a secure and unassailable base from which to operate. The Arab forces operated from secure desert camps and oases that the enemy could neither locate nor attack. Second, the irregular force must be engaged with a technologically sophisticated enemy, a conventional military force. The Turkish army that the Arabs faced was a conventional European force that relied on conventional training and modern weaponry and communications. Third, the enemy force must lack sufficient numbers of troops to dominate the battle area from widespread fortifications. The Turkish army only had sufficient numbers to guard important outposts and selected areas of railway; they could not control the majority of the Arabian land area. Fourth, the irregular force must have at least the passive support of the population, where the local people would provide information on the enemy and also not betray the irregular forces. Lawrence felt that a successful rebellion could be made up of 2 percent of the population, if the other 98 percent was supportive. The population in the Middle East was overwhelmingly supportive of the Arab irregulars who they saw as leading a struggle for liberation against foreign invaders and for the establishment of an Arab state. The fifth principle is that the irregular force must have speed, endurance, presence, and independent lines of supply. Lawrence's irregular forces, relying heavily on camels, demonstrated these characteristics and were able to gain and keep the initiative in the war. The desert war was similar to war at sea. The Arab forces could come and go where they pleased, without being tied down to supply lines, roads, or railways. The final principle is that the irregular force must have the technical ability to attack the enemy's logistics and communications vulnerabilities. Lawrence's force used small arms, explosives, and mechanical methods to attack the Turkish railway and telegraph infrastructure, providing some Clausewitzian friction to Turkish operations and requiring the enemy to continually expend dwindling resources to effect repairs. Lawrence summed up his irregular warfare thesis as: "In fifty words: Granted mobility, security (in the form of denying targets to the enemy), time, and doctrine (the idea to convert every subject to friendliness), victory will rest with the insurgents, for the algebraical factors are in the end decisive, and against them perfections of means and spirit struggle quite in vain."[14]

Legacy and Significance

T.E. Lawrence is not as well known as many of the great military leaders or philosophers. His Arabian exploits, while popular with the public, did not receive the same attention of historians as the great battles on the European mainland. Lawrence was neither the first nor the last to develop and implement a theory of irregular warfare. He did not write volumes about military strategy and is not as well known as the greats like Sun Tzu, Jomini, or Clausewitz. He did, however, have an impact on both the public imagination and the study and practice of asymmetric warfare that continues to the present day.

Lawrence's experiences and writings have influenced several commanders and military theorists in the last 80 years. In a 1946 interview, Vo Nguyen Giap, the Vietnamese general who orchestrated the insurgency that led to the military defeat of both the French and the Americans, stated, "My fighting gospel is T.E. Lawrence's Seven Pillars of Wisdom . I am never without it."[15] The eminent British military writer, Basil Liddell Hart, advocate of maneuver warfare and armored forces, was Lawrence's biographer and friend and considered him a military genius. He saw Lawrence's irregular strategy as a validation of his own notion of the "indirect approach" to warfare and an indictment of the attritional methods used on the Western Front during the First World War.[16] The prominent American counterinsurgency writer, John Nagl, was heavily influenced by Lawrence's writings and titles his book after Lawrence's statement in Seven Pillars of Wisdom that for conventional armies, making "war on rebellion was messy and slow, like eating soup with a knife."[17] Nagl also wrote the forward to the new U.S. counterinsurgency manual (discussed below) and Lawrence's influence is apparent throughout that document. Lawrence's significance is that he both conducted and wrote about successful irregular warfare and developed and articulated clear principles that can be applied to other asymmetric conflicts. His philosophy on irregular warfare complements the writings of many others, such as Sun Tzu, and is simple to comprehend and emulate.

Lawrence's primary legacy is the vivid demonstration of the potential effectiveness of irregular troops in a protracted struggle against a conventional force. It is true that Lawrence's exploits took place in a sideshow to a small campaign that was part of a much larger war in Europe. The Middle East was never the point of main effort for any of the great powers engaged in that war. Lawrence showed, however, that small, mobile forces, deploying from and returning to safe havens, attacking when and where they like, could have a significant impact against larger better-equipped armies that relied on conventional weapons and tactics and were denied the chance for a decisive battle. The longer the struggle persisted, the more effective the irregular forces became. The Vietnamese, Communist Chinese, and other successful insurgencies since the Arab Revolt have replicated and validated Lawrence's example of asymmetric warfare.

Applicability for Present and Future Warfare

The principles of irregular warfare that Lawrence outlines are applicable in the counterinsurgency (COIN) operations that are ongoing against insurgents and terrorists in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Lawrence's principles and his experiences in the Arab Revolt reveal several characteristics of irregular warfare that are relevant in today's asymmetric conflicts.

The first of these is that, to the insurgent or guerrilla, time is a weapon. Irregular operations will always be offensive and protracted. Insurgents are not inclined to try to defend territory or seek quick victories. The insurgent usually has the initiative, and a long campaign that erodes the will of the stronger force is in his interest. This was demonstrated in the Vietnamese victory over France and the United States and is an important aspect of the current struggles in Afghanistan and Iraq. Democracies generally have a difficult time keeping public support for a long, inconclusive war. Americans, especially, desire a quick, decisive, and relatively bloodless conclusion to military operations. Successful insurgents know this and use it to their advantage.

Secondly, the international media is a potent weapon that irregular forces can use to support their struggle, shaping popular opinion both home and abroad, and also serving as a means to recruit, obtain financial support and erode the enemy's will. This is especially true in the age of rapid high-quality electronic media such as television, the Internet, mobile phones, etc.

Third, irregular forces are more effective when they operate in small groups rather than large formations. If insurgents or terrorists operate in large formations, they are easier for conventional forces to locate and destroy; they are playing to the stronger forces' advantage. The Taliban experienced this in Afghanistan when they attempted to operate as company-size military formations against coalition forces and suffered high casualties as a result. They have since returned to the tactics of using smaller, more stealthy units.

Another characteristic of irregular warfare is the importance for the stronger power to have enough "boots on the ground" to effectively exert control over an area. Lawrence understood this as part of the "algebraical" element of the insurgency. The importance of adequate numbers for COIN operations was vividly demonstrated by the U.S. troop surge in Iraq. Although other factors were involved, the increase in the number of troops in the contested areas during the surge was the main reason that the insurgency was, for the most part, broken.

The current irregular conflicts demonstrate the reality that the insurgents will usually have more precise and accurate intelligence about the occupying force. They are usually part of the population in the area in dispute and have intelligence sources and local knowledge. This allows the insurgents to attack at a time and place of their choosing and then withdraw. The larger force will rarely have this amount of timely and accurate intelligence and will often be reactive as a result.[18]

The applicability of Lawrence's principles of irregular warfare to current and future counterinsurgency operations is reflected in the recent U.S. Army and Marine Corps COIN field manual, FM 3-24 Counterinsurgency. This was the first major manual of its kind published for the U.S. military in decades and is indicative of the importance of COIN conflicts to the United States currently and of Lawrence's influence on this type of warfare. This manual directly refers to Lawrence in several instances and describes the nature of insurgencies in terms that he would recognize. The manual outlines several important aspects of insurgencies. These include the asymmetric nature of irregular or insurgent forces, the difficulties of conventional forces to deal with insurgents, the importance of the support of the population and use of the media, and, most importantly, that the insurgents seek a long campaign that will exhaust the stronger forces.[19] The manual also illustrates the importance of the host nation's role in multinational COIN operations by Lawrence's admonition to a fellow British liaison officer to "not try to do too much with your own hands. Better the Arabs do it tolerably than you do it perfectly. It is their war, and you are to help them, not to win it for them."[20] The applicability of this view to recent criticism of the new Iraqi and Afghan government security services is clear.

Irregular warfare will likely be a reality that conventional armies have to face in the near to medium term. Throughout history, asymmetric warfare has long been a tool of the weaker side in a conflict. As traditional nation-states undergo traumatic change and old balances of power erode, conventional war between states will become less likely and non-state actors such as insurgents, terrorists, and smugglers will emerge in increasing numbers. These groups, while growing in power and sophistication, will not usually be able to face conventional armies in open battle and will have to adopt asymmetric tactics, including irregular warfare. Insurgent forces will use the principles that Lawrence described and followed, as they have been proven effective in many campaigns since his battles in the desert. Large armies, like those of the United States, are trained and equipped primarily to wage conventional warfare against similar forces. They are, in many ways, like the conventional Turkish army that found itself trapped in Arabia, trying to destroy a smaller force that it could neither locate nor engage. While changes can, and are, being made to allow armies to reconfigure and adapt for counterinsurgency and other asymmetric operations, modern armies face the dilemma that they cannot be focused on countering asymmetric warfare only. They still must retain the capability to fight and win "normal" wars. Asymmetric struggles rarely pose an existential threat to a major power. The threat of conventional ground, air, or naval warfare, including weapons of mass destruction, will not disappear, and military planners must ensure heavy forces are available to address that threat. The challenge for the United States and other countries will be to determine the correct balance, or "force mix" between conventional and unconventional forces to meet all likely scenarios, both conventional and asymmetric. It is clear, however, that asymmetric warfare will continue as a significant threat to the United States and other nations for the foreseeable future. Asymmetric forces will steadily increase in numbers and military capability. In this environment, both regular and irregular forces alike will be well served by an understanding of Lawrence's principles of irregular warfare and the means to counter them.

Conclusions

The legend of T.E. Lawrence, or "Lawrence of Arabia," was a creation of both his real exploits and extensive media exposure, much of dubious accuracy. Lawrence's eccentric personality and behavior added to the mystery about what really happened in the desert from 1916-18. The reality is that Lawrence, assisting the Arab forces facing the Turks, conceived and executed a two-year irregular warfare military campaign that is a dramatic example of effective asymmetric warfare. His cultural and personal qualities gave him influence and motivated the Arab fighters to follow an outsider. In a difficult and harsh operational environment, he seized and maintained the initiative, capitalizing on his advantages of speed and mobility. He caused the Turks to expend huge amounts of resources and allocate numbers of troops to guard fixed outposts and lines of communication out of all proportions to the personnel that Lawrence employed. More importantly, he prevented those forces from being used elsewhere in a more effective manner. The irregular Arab forces were essentially pinning down the Turks through an asymmetric strategy. Although his operations were only a small supporting piece in the overall conduct of the First World War, Lawrence's campaign demonstrated the potential effectiveness of irregular forces against conventional troops and the difficulties that conventional armies face in combating these forces.

In addition to his military accomplishments, Lawrence wrote extensively after the war and clearly expressed his philosophy of irregular warfare. While Lawrence is not as well known as some of the great military philosophers, he did leave a written legacy that included simple and insightful principles of irregular warfare, principles that irregular forces around the world are applying today. His writings influenced future military writers and generals and the principles of irregular warfare that he outlined are still relevant for insurgent and counterinsurgent alike in the ongoing asymmetric conflicts such as those in Iraq and Afghanistan. Although not as well known as some, except for inaccurate movie portrayals, Lawrence's successful waging of asymmetric warfare and his principles for successful asymmetric operations make him a "Forgotten Master" whose relevance will continue to be significant for the small scale conflicts that are currently part of our world and appear to remain so in the near and medium term.

| * * * |

Show Notes

| * * * |

© 2026 Evan Pilling

Written by Evan Pilling. If you have questions or comments on this article, please contact Evan Pilling at: evan_pilling@hotmail.com.

About the author:

Evan Pilling is a retired naval intelligence and surface warfare officer currently employed as a civilian antiterrorism intelligence specialist with the US Army Reserve Command. He has a Master of Science in National Security Affairs from the US Naval Postgraduate School and lived and worked in the Middle East for over a decade.

* Views expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily represent those of MilitaryHistoryOnline.com.