Cairo's Fortress on the Mountain

By David W. Tschanz, PhD

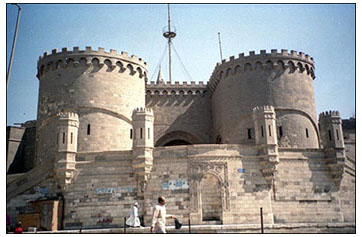

Cairo residents call it the Qal'at al-Jabal, the Fortress on the Mountain, or just al-Qal'ah, the Fortress. The rest of the world simply calls it “The Citadel.” For nearly a millennium it has stood as a silent sentinel, residence, and symbol of power.

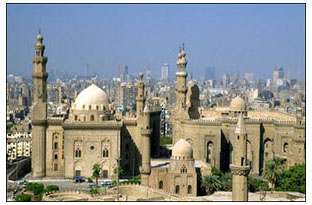

Standing on its battlements, and looking westwards provides a view of over 4500 years of architectural marvels from the mosque of Sultan Hasan, just below to the Pyramids of Giza across the Nile. From atop this fortress the awesome sweep of history is a vivid reality. It is a view that must have given even the sultans who ruled from here, cause to reflect.

But bejeweled rulers and their pampered servants and ministers were not the only ones who toiled here. It takes only a moment and a little imagination to find yourself following the footsteps of the bowmen who once manned the12th-century walls, defending the glistening city along the Nile against all enemies. Just below the battlements, a maze of stairways leads into labyrinths of narrow galleries within the walls. Arrow slits a few inches wide and set at precise angles to give defending archers greater protection create an eerie pattern of alternating shafts of shadow and sunlight.

Watching over Cairo from a spur of limestone detached from its parent Moqattam Hills by quarrying, the Citadel is among the world’s great monuments to medieval warfare, as well as one of the Egyptian capital’s most highly visible landmark along its eastern skyline.

Watching over Cairo from a spur of limestone detached from its parent Moqattam Hills by quarrying, the Citadel is among the world’s great monuments to medieval warfare, as well as one of the Egyptian capital’s most highly visible landmark along its eastern skyline.

The area where the Citadel is now located began its life not as a great military base of operations, but as the "Dome of the Wind", a pavilion created in 810 by Governor Hatim Ibn Hartama, who wanted to take advantage of the areas’ cool breeze and its view of Cairo.

It’s role as a pleasure spot ended somewhat abruptly when war, and the threat of war, caused the great general and military leader Saladin to exploit the site’s strategic location as a fortress.

Saladin

Saladin, who was born in Tikrit, Iraq, and a vassal of the northern Syrian ruler Nur al-Din ibn Zanki, first came to Egypt in 1163. At that time, Egypt's ruling Fatimid dynasty, though immensely rich, was militarily weak. Egypt depended on trade between East and West, but all of the Egyptian ports in Palestine and Syria - where most of the camel caravans coming from the Far East and Persia ended - had been lost to the Crusaders. When Amalric I, the Latin king of Jerusalem, began attacking Egypt, the Fatimid caliph in Cairo, al-'Adid, appealed to Nur al-Din ibn Zanki for help.

In 1163, Nur al-Din sent an army to Egypt under the command of General Asad al-Din Shirkuh, who was accompanied - somewhat reluctantly - by his nephew Saladin. After repelling the Crusaders, they returned home to Syria. Later the Crusaders attacked Alexandria, and Shirkuh and Saladin were called back to deal with them again. In 1168, they returned to Egypt a third time, driving the Crusaders from the outskirts of Cairo and forcing them back to Palestine.

In 1163, Nur al-Din sent an army to Egypt under the command of General Asad al-Din Shirkuh, who was accompanied - somewhat reluctantly - by his nephew Saladin. After repelling the Crusaders, they returned home to Syria. Later the Crusaders attacked Alexandria, and Shirkuh and Saladin were called back to deal with them again. In 1168, they returned to Egypt a third time, driving the Crusaders from the outskirts of Cairo and forcing them back to Palestine.

This time Shirkuh and Saladin stayed on in Cairo, and the Fatimid caliph made Shirkuh his vizier. But within two months, the elderly Shirkuh died, and the caliph chose young Saladin to succeed his uncle.

When the caliph himself died in 1171, amid growing political instability throughout Egypt, Saladin seized power from the ailing Fatimids and established his own Ayyubid dynasty. Yet, during his 24-year reign, Saladin spent very little time in Cairo - he was always away, relentlessly campaigning against the Crusaders in Syria and Palestine.

Saladin's priorities were to protect Egypt from further Crusader attacks and to secure his own position in the face of lingering pro-Fatimid resentment of his takeover. Egyptian historian Taqi al-Din al-Maqrizi (1364-1442) tells us that, on returning to Cairo in September 1176, Saladin decreed that "a citadel" should be built. He also gave orders "to make a new enclosure" - in effect, to extend the walls of al-Qahirah, the private palace-city of the deposed Fatimids, and include within it the old Umayyad city of al-'Askar and Ibn Tulun's ninth-century town of Qata'i'. In one stroke, Saladin made al-Qahirah - Cairo - a city 10 times its previous size and increased the security of the site where he planned to build his new fortress.

Early Years

According to local tales, Saladin selected the location not only for its military value but because of this healthy air. The story goes that he hung pieces of meat up all around Cairo. Everywhere the meat spoilt within a day, with the exception of the Citadel area where it remained fresh for several days, hence its selection. The story bears a strong resemblance to the description of the much earlier great Muslim physician, Ar-Razi (Rhazes), selected the site of Baghdad’s hospital. It is impossible to say whether Saladin used Ar-Razi’s methods, or if the stories became confused and incorrectly ascribed to Saladin.

According to local tales, Saladin selected the location not only for its military value but because of this healthy air. The story goes that he hung pieces of meat up all around Cairo. Everywhere the meat spoilt within a day, with the exception of the Citadel area where it remained fresh for several days, hence its selection. The story bears a strong resemblance to the description of the much earlier great Muslim physician, Ar-Razi (Rhazes), selected the site of Baghdad’s hospital. It is impossible to say whether Saladin used Ar-Razi’s methods, or if the stories became confused and incorrectly ascribed to Saladin.

Either way it is doubtful that the great general chose the site for its “healthy air” and not its strategic advantages both to dominate Cairo and to defend outside attackers.

An Ayubbid, Saladin was also a longtime resident and ruler of Syria, where every town had some sort of fortress to act as a stronghold for the local ruler so it was only natural that he would carry this custom to Egypt.

Construction and Design

Work on the Citadel began in 1176, supervised by Saladin's loyal vizier, Baha' al-Din Qaraqush, or "Black Eagle." The most modern fortress building techniques of that time were used to construct the original Citadel. Great, round towers were built protruding from the walls so that defenders could direct flanking fire on those who might scale the walls. The walls themselves were ten meters (30 ft) high and three meters (10 ft) thick.

The Bir Yusuf (Saladin’s Well) was dug in order to supply the occupants of the fortress with an inexhaustible supply of drinking water. Some 87 meters (285 ft) deep, it was cut though solid rock down to the water table. It is not simply a shaft. There is a ramp large enough so that animals could descend into the well in order to power the machinery that lifted the water.

Writing in 1182, the Valencian traveler Ibn Jubayr, who visited Cairo, described the work in progress:

"We looked upon the building of the Citadel, an impregnable fortress adjoining Cairo, which the sultan thinks to take as his residence.... The forced laborers on this construction and those executing all the skilled services and vast preparations - such as sizing the marble, cutting the huge stones and digging the moat that girdles the walls, hollowed out with pick-axes from the rock - are all foreign Christian prisoners whose numbers are beyond computation."

When completed the Citadel must have presented a formidable sight. The eastern wall rose sheer out of a rocky gorge, deepened to make it more inaccessible. The northern, southern and western walls - equally massive - looked out across open desert to the two nearby cities of al-Fustat and Cairo.

When completed the Citadel must have presented a formidable sight. The eastern wall rose sheer out of a rocky gorge, deepened to make it more inaccessible. The northern, southern and western walls - equally massive - looked out across open desert to the two nearby cities of al-Fustat and Cairo.

Unfortunately, little remains of the original fortress except a part of the walls and Bir Yusuf, the well that supplied the Citadel with water. The Ayyubid walls that circle the northern enclosure are 33 ft tall and 10 ft thick; they and their towers were built with the experience gleaned from the Crusader wars.

After Saladin

Ironically, Saladin never lived in his Citadel; it was not completed until shortly after his death. Despite his fame, he was at heart a humble, religious man, and whenever he was in Cairo he preferred to stay at a modest house down in the city, rather than in one of the Fatimid palaces. When he died in 1193, the empire he created extended from Cairo to Aleppo in northern Syria, to the borders of Mesopotamia, and southward along the Nile into Nubia, and included Yemen and parts of western Arabia.

After the death of Saladin, his nephew, Al-Kamil, reinforced the Citadel by enlarging several of the towers. Specifically, he encased the Burg al-Haddad (Blacksmith's Tower) and the Burgar-Ramlab (Sand Tower) making them fully three times larger. These two towers controlled the narrow pass between the Citadel and the Muqattam hills. Al-Kamil also built a number of great keeps around the perimeter of the walls, three of which can still be seen overlooking the Citadel parking area. These massive structures were square, up to 25 meters (80 ft) tall and 30 meters (100 ft) wide. In 1218, al-Kamil, now the Sultan, moved his residence to the Citadel building his palace in what is now the Southern Enclosure. While the palace no longer exits, until the construction of the Abdeen Palace in the mid-19th century, it was the seat of government for Egypt.

In the mid-13th century, the only woman ever to rule from the Citadel - Shajarat al-Durr, or "Tree of Pearls" - reigned as sultana for just 80 days before abdicating in favor of her husband, who was a Mamluk, a member of the "slave" military corps that had been the backbone of both the Fatimid and Ayyubid dynasties.

A Mamluk sultan, Baibars al-Bunduqdari (1260-77) isolated the palace compound by building a wall that divided the fortress into two separate enclosures linked by the Bab (gate) al-Qullah. The area where the palace once stood is referred to as the Southern Enclosure, while the larger part of the Citadel proper is referred to as the Northern Enclosure.

An-Nasir Muhammad, a fascinating Mamluk ruler who reigned and was deposed three times (1294-1295, 1299-1309 and 1310-1341), but is still considered the greatest Mamluk sultan, tore down most of the earlier buildings in the Southern Enclosure and replaced them with larger structures. For his new palace, al-Nasir Muhammad borrowed the design of the famous Qasr al-Ablaq, the so-called Striped Palace, in Damascus. To grace the main diwan, or audience hall, al-Nasir had 32 colossal columns of Aswan red granite removed from some forgotten pharaonic temple and hauled up to the Citadel. Five centuries later, drawings by Napoleon's savants would capture this magnificent chamber, known as the Hall of Columns, in all its decaying glory.

An-Nasir Muhammad, a fascinating Mamluk ruler who reigned and was deposed three times (1294-1295, 1299-1309 and 1310-1341), but is still considered the greatest Mamluk sultan, tore down most of the earlier buildings in the Southern Enclosure and replaced them with larger structures. For his new palace, al-Nasir Muhammad borrowed the design of the famous Qasr al-Ablaq, the so-called Striped Palace, in Damascus. To grace the main diwan, or audience hall, al-Nasir had 32 colossal columns of Aswan red granite removed from some forgotten pharaonic temple and hauled up to the Citadel. Five centuries later, drawings by Napoleon's savants would capture this magnificent chamber, known as the Hall of Columns, in all its decaying glory.

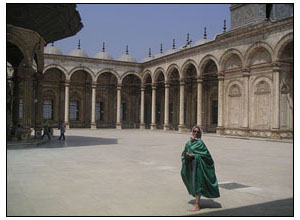

Unfortunately, the only remaining structure left from his building period is the An-Nasir Mohammed Mosque, designed to hold 5000 worshippers. It was begun in 1318 and finished in 1355 and is located near the enclosure gate. Like the pillars that once graced the Hall of Columns, massive pharaonic columns support the highest arches of the mosque, while a forest of Roman and Byzantine marble pillars supports a series of smaller arches.

The mosque's twin minarets, capped with green, turquoise and white tiles, recall Isfahan and Central Asia, and were probably decorated by craftsmen brought specially from Tabriz in Persia. One minaret was positioned to allow the daily call to prayer to reach the barracks area of the Northern Enclosure, and the other was directed at the Southern Enclosure and beyond to the city below.

He also built a great Hall of Justice with a grand, green dome that towered above the other structures in the Southern Enclosure.

Beside it was built the Qasr al-Ablaq (Striped Palace) with its black and yellow marble. This palace, used for official ceremonies and conducting affairs of state, had a staircase leading down to the Lower Enclosure and the Royal Stables where An-Nasir kept 4,800 horses.

The Ottoman Period

The Ottoman Period

The Ottomans controlled Egypt in one way or another between 1517 and the early 20th century, except for a brief French occupation. Much of what is now at the Citadel actually dates from this period. Near the far end of the Northern Enclosure is the Suleiman Pasha Mosque. It was the first Ottoman style mosque built in Egypt and dates from 1528. It was built to serve the early Ottoman troops.

The Lower Enclosure, where the stables of An-Nasir were came to be known as the al-Azab because some of the Ottoman soldiers, known as the Azab regiments, were stationed in the Lower Enclosure. The word Azab can be translated as bachelor and is fitting for these troops who were not allowed to wed until after they retired.

From the late 16th century until the French occupation, the strict military structure of the Ottoman soldiers gradually deteriorated. During this period, the Azab troops began to marry, and were even allowed to build their own housing within the fortress. By the mid 17th century, the Citadel had become an enclosed residential district with private shops and other commercial enterprises, as well as public baths and a maze of small streets.

The Ottomans rebuilt the wall that separates the Northern and Southern Enclosures, as well as the Bab al-Quallah. They also built the largest tower in today's Citadel, the Burg al-Muqattam which rises above the entrance to the Citadel off Salah Saalem Highway. This tower is 25 meters (80 ft) tall and has a diameter of 24 meters (79 ft). In 1754 the Ottomans rebuilt the walls of the Lower Enclosure and added the fortified Bab el-Azab gate.

Ali Pasha

The Ottoman Muhammad Ali Pasha, one of the great builders of modern Egypt, came to power in 1805, and was responsible for considerable alteration and building within the Citadel. He rebuilt much of the outer walls and replaced many of the decaying interior buildings. He also reversed the roles of the Northern and Southern Enclosures, making the Northern Enclosure his private domain, while the Southern Enclosure was opened to the public.

The Ottoman Muhammad Ali Pasha, one of the great builders of modern Egypt, came to power in 1805, and was responsible for considerable alteration and building within the Citadel. He rebuilt much of the outer walls and replaced many of the decaying interior buildings. He also reversed the roles of the Northern and Southern Enclosures, making the Northern Enclosure his private domain, while the Southern Enclosure was opened to the public.

The entire corps of Mamluk princes, suspected of plotting to overthrow Muhammad 'Ali, was massacred within the Citadel in a single afternoon. On March 1, 1811, the viceroy invited the entire Mamluk corps to a special levee. The 475 princes entered the Citadel on horseback, in their customary splendor. Muhammad 'Ali conversed calmly with them and then took his leave. As the princes began to depart, two inner gates of the Citadel were sealed and soldiers above opened fire on the trapped Mamluks. Muhammad 'Ali, listening to the shots ring out, is said to have asked for "a glass of water."

The Muhammad Ali Mosque, also known as the Alabaster Mosque, is built in Ottoman Baroque and imitates the great religious mosques of Istanbul, and dominates the Southern Enclosure. Ottoman law prohibited anyone but the sultan from building a mosque with more than one minaret, but this mosque has two. This was one of Muhammad Ali's first indications that he did not intend to remain submissive to Istanbul.

Behind Muhammad Ali’s gilded mosque stands a far more elegant one, the Mosque of al-Nasir Muhammad. The beautifully crafted masonry, the elegant proportions, the ornate but controlled work on the minarets, all indicate that the building is a Mamluk work of art. The conquering Ottomans carried much of the original interior decoration off to Istanbul, but the space is nevertheless impressive. The supporting columns around the courtyard were collected from various sources including ancient Egyptian structures.

South of the Muhammad Ali mosque in the Hawsh is the Gawharah (Jewel) Palace. This structure was built between 1811 and 1814 and housed the Egyptian government until it was later moved to the Abdeen Palace.

Just through the Bab al-Qullah in the Northern Enclosure one finds Muhammad Ali's Harem Palace that was built in the same Ottoman style as the Jewel Palace. The palace served as a family residence for the Khedive until the government was moved to Abdeen Palace.

Modern Era

The Citadel functioned as a military hospital during the British occupation and was returned to Egyptian control after World War II.

The Citadel functioned as a military hospital during the British occupation and was returned to Egyptian control after World War II.

Since 1949 the Citadel has housed the Military Museum of Egypt, originally founded by King Faruq. While the Museum has many artifacts illustrating warfare in Egypt, one of the most interesting attractions is the Summer Room. This room contains an elaborate system of marble fountains, basins and channels meant as a cooling system, and are probably the last such example in Cairo.

In the livery court behind the carriage gate of the museum is a statue of Sulayman Pasha that originally stood in the city center. Just beyond this museum is a small Carriage Museum in what was the British Officer's mess until 1946. Borrowed from the larger Carriage Museum in Bulaq, it contains eight carriages used by the Muhammad Ali family. Just behind this museum is the Burg at-Turfah (Masterpiece Tower), one of the largest of the square towers built by al-Kamil in 1207.

The National Police Museum is also located at the Citadel. It was built over the site of the Mamluk Striped Palace just opposite the Mosque of an-Nasir Muhammad. It has displays of law enforcement dating back to the dynastic period. The terrace also provides a wonderful view of Cairo.

| * * * |

Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. 1989. Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction. Leiden; New York: E.J. Brill, 66.

Jarrar, Sabri, András Riedlmayer, and Jeffrey B. Spurr. 1994. Resources for the Study of Islamic Architecture. Cambridge, MA: Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture. http://archnet.org/library/documents/one-document.jsp?document_id=6053.

Rabbat, Nasser O. 1995. The Citadel of Cairo: A new interpretation of Royal Mamluk Architecture. Leiden; New York: E.J. Brill.

Rabbat, Nasser O. 1989. The Citadel of Cairo. Geneva : Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

Williams, Caroline. 2002. Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, pp.195ff.

| * * * |

© 2026 David W. Tschanz, PhD

Written by David W. Tschanz,

About the author:

David W. Tschanz currently lives in Florida after a 23 year stint in Saudi Arabia from 1989-2012. He has been a contributor to Command Magazine, Strategy & Tactics and StrategyPage.com, Against the Odds and Wild West among others for more than three decades. He has written over 1100 published articles and nine books on a variety of topics ranging from military history to designing Exchange Server infrastructure. He currently edits and publishes Cry “Havoc!” the journal of Mensa’s Military History Special Interest Group and is chairman of the Venice, FL Civil War Roundtable.

* Views expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily represent those of MilitaryHistoryOnline.com.