1127 Days of Death – a Korean War Chronology – Part I, 1950

By Anthony J. Sobieski

The Korean War, forever known as the ‘Forgotten War’ by many, lasted a total of 1127 days, from June 25th 1950 through July 27th 1953. A total of 38 months. A little over three years in length, but encompassing four years on a calendar. With a beginning that was unlike any other beginning of a ‘war’ up until then, the term ‘Police Action’ became its moniker for many years, with some in the United States and other countries looking to call it anything other than what it really was. It was just too short a time after the end of World War II, with the sacrifices by many, the devastation of so much, burned into people’s memories all too readily. And during the war, who could have guessed there would be an ending that harkened back to the days of World War I, the war to end all wars. Trench warfare and bunkers, large amounts of artillery, and a set day and time to stop shooting. The Korean War was and is a difficult war to describe. Most of the weapons, equipment and tactics were WWII era. Yes, there were some new innovations to the art of killing another human being and to the survival from being killed. But they were far and few between. Personal body armor made its first appearance, and winter ‘Mickey Mouse’ boots, and of course Korea was the first truly jet-age war. Helicopters made their debut, performing search & rescue along with speedy transportation of the wounded. But other than those and a few more, the war was fought with WWII era rifles, artillery, ships (excluding the newer carriers), and at least in the very beginning of the war, fighters, bombers and tanks. Even some of the first men to serve in combat were WWII veterans, many of whom who had already given ‘a pound of flesh’ in the service to their country.

There were 14,725 U.S. servicemen killed in 190 days of combat in 1950. That’s an average of 77 men per day, a staggering number compared to the likes of today’s ‘standards’ of what would be an acceptable death rate in modern conflicts. Remember, the numbers quoted in this article are those KILLED, not wounded. In comparison, 1968 was the deadliest year of the Vietnam War, where 16,899 were killed, for an average of 46 deaths per day. To look at it from another perspective, if the violence of the first year of the Korean War lasted 365 days, there would have been approximately 28,287 deaths during that first year alone. 1950 Korea certainly was a violent place to be.

Before going any further a note about how all of this is reported and recorded. ‘Killed In Action’, or KIA, applies to the vast majority of all deaths in Korea. However, KIA does not include ALL deaths. As in any war, there are tragedies, both purposeful and accidental. The Korean War had its share. Included in these numbers are those who lost their lives, maybe not by an enemies’ bullet or artillery shell, but still during war and still in the service of their country. Aircraft accidents, drowning’s, vehicle accidents and roll-overs (which were very common), fratricide, hemorrhagic fever, other natural diseases, heart attacks, and just about any other way imaginable for a human being to die. All played a part in adding to the death toll. These numbers are all included in the U.S. Government’s statistics of the war, and where possible, are identified as ‘DOC’ Died Other Causes, or ‘Aircraft Crash’ or something similarly descriptive, which made it no less painful for the families back home.

It’s hard to imagine now, but so many monumental moments in U.S. military history from the war happened in those first 190 days of combat. The trials and tribulations of ‘Task Force Smith’, that ill-equipped, ill-trained and ill-fated force sent to Korea in early July. And the numerous ‘Battle of…’ that occurred one right after another. In quick succession, there were the Battles of Osan, Kum River, Taejon, the Notch, First and Second Battles of Naktong Bulge, the Bowling Alley, Unsan, Chosin Reservoir, Kunu-ri, and finally Koto-ri. All within six months, all with numerous casualties. And let’s not forget the defense of the Pusan Perimeter, the Naktong Perimeter breakout, the Inchon Landing and subsequent liberation of Seoul, the drive to the Yalu, and the almost inevitable Chinese intervention and counter-offensive which drove the U.S. forces from the north and changed the entire face and eventual outcome of the war. The only sea battle of the war happened in 1950, with the USS Juneau helping destroy three North Korean torpedo boats. The year also saw the first jet vs jet air-to-air combat in history, with an F-80 Shooting Star shooting down a Mig-15. And the war’s first airborne operation, with the 187th Airborne Infantry Regiment and the 674th Field Artillery Battalion making a combat jump north of Pyongyang, the North Korean capital.

There were 49 Medals Of Honor (MOH) awarded for actions during 1950, out of the eventual 146 MOH medals awarded for the entire war, and these covered all four branches of military service. There was one each awarded to Air Force and Navy members, 19 awarded to Marines, and 28 awarded to Soldiers. One thing about the Medal Of Honor that was not particular to Korea was the KIA rate of those who received the medal: 35 of the 49 medals were awarded posthumously.

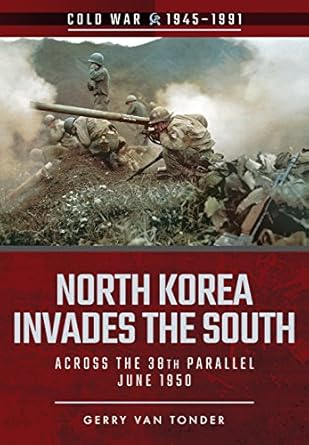

June 1950 - 31

31 men were killed in the last six days of June 1950 that were the start of the Korean War. It was an inauspicious start. The North Korean Army invaded on June 25th and the U.S. response started three days later. So, technically, those 31 men died in three days in June 1950. June 28th was the first day of the war that a U.S. serviceman was KIA. The fledgling USAF has the distinction of having the first deaths of the war. Two B-26s and an F-82 Twin Mustang all crashed in bad weather while returning from combat runs against North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) positions. On the 29th another B-26 augured in during a combat run on a train. And on the 30th, one of the first tragedies of the war occurred, when a C-54G Skymaster from the 22nd Troop Carrier Squadron, transporting members of the 71st Signal Battalion, crashed into a hillside northwest of Pusan, killing all 23 personnel onboard.

July 1950 - 2919

July 1950 was the first full month of combat operations during the war. 2919 men lost their lives in Korea during July, and it would not be the last month with this type of number before the end of 1950. The first four days of the month only had 2 deaths, again Air Force personnel lost in downed aircraft, but these days were just an anomaly for things to come. Task Force Smith, the very first U.S. Army personnel to be sent to Korea to fight, was eventually in position and engaged the enemy on July 5th through July 8th resulting in over 160 KIAs. This was the battle of Osan, the first ground combat of the war for U.S. forces. There were also more aircrew deaths during this time as 3 more F-80 pilots were KIA. The 21st Infantry Regiment, now in Korea en-masse, was fully committed to battle on July 10th around the town of Chochiwon in an effort to delay advancing North Korean units. This ‘effort to delay’ took another 422 lives from the ranks of the 21st Infantry and U.S. military. July 13th saw the first B-29 Superfortress loss of the war, with all 6 aircrew KIA. And on the 14th, the 63rd Field Artillery Battalion was overrun near the Kum River, resulting in 60 KIA, in what would be the first of a number of times during the war that a U.S. artillery battalion would be so close to the front lines as to be overrun by the enemy. This was also the precursor to the July 16th Battle at the Kum River, where the 19th Infantry Regiment and attached units were hit hard in yet another ‘delay action’ resulting in 418 KIA. On the 17th and 18th a few more F-80s and F-51s were lost, along with their pilots. This was quickly followed up by the Battle of Taejon on July 19-20 where it was mostly the 34th Infantry Regiment and supporting units turn to add to the numbers of killed, losing 649 more men in two days. Between July 24th and the 26th elements of the 1st Cavalry Division were in Korea and began seeing action, with the 5th and 8th Cavalry Regiments losing a large portion of the 321 KIA around Yongdong in those three days. The last major action of July occurred on the 27th during the Hadong Ambush where the 29th Infantry Regiment, fighting around the small town of Anui, lost 320 men (103 from ‘B’ Company alone) of the 357 who were KIA on that day. For the remainder of the month, small actions involving the 5th, 7th and 8th Cavalry Regiments, and the 19th, 24th, 29th, 34th Infantry Regiments, along with a smattering of other units, provided another 366 men to the death toll.

August 1950 - 1828

August 1950 saw another 1828 men killed in Korea. The holding and delay actions of July were an attempt to slow the advance of the NKPA as it overran the south. Heading into August, as U.S. forces withdrew along the Naktong River, there were numerous small unit actions around the towns of Taegu, Masan, and P'ohang, all leading to Pusan. The Battle of the Notch started on August 2nd thru the 3rd with numerous units participating and giving another 158 KIA to the lists. Most of these KIA came from the 5th and 8th Cavalry Regiments and attached units fighting around the Taegu area and the 19th, 27th and 29th Infantry Regiments fighting on the actual Notch near the town of Masan. This battle can be considered the ‘high-water-mark’ for the NKPA’s southern drive and the beginning of the defense of the Pusan Perimeter. There were two battles in August that were part of the Pusan defensive strategy. The First battle of the Naktong Bulge was fought between August 8-18. This was the first engagement where 2nd and 25th Infantry Division troops, fresh to Korea, took part in the fighting. On August 5th there were two losses of F-51Ds and a Navy F4U Corsair, all 3 pilots shot down during bombing or strafing runs. The next few days saw a consistency in numbers of KIA. Task Force Kean was formed under the 25th Infantry Division commander on August 7-8, and also showed the first number of Marines KIA with 28 dead from the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade (1st PMB) out of the 122 total dead for these two days. Task Force Hill was formed on August 9th under the 9th Infantry Regiment commander. This task force was a large force with numerous attached units and was used in an attempt to drive the NKPA from the east bank of the Naktong River. 522 KIA were recorded in only four days of fighting with Task Force Hill. Another small action called the Battle of the Bowling Alley, which started out as a Republic of Korea (ROK) battle, eventually involved elements of the 23rd and 27th Infantry Regiments. Through the middle of the month the Naktong Bulge battle continued, taking a daily death toll of an average of 75 men a day from various engaged units.

The middle of August the U.S. military would experience the first reported episodes of war crimes in two separate incidents. On August 12th, in what was to become called the ‘Bloody Gulch Massacre’, after hard fighting around the town of Masan, 45 men from the 555th Field Artillery Battalion, 23 men from the 5th Regimental Combat Team, and 11 men from the 90th Field Artillery Battalion were executed by their NKPA captors. The next week on August 17th during a smaller engagement of the Pusan Perimeter called the Battle of Taegu in what was coined the ‘Hill 303 Massacre’, 41 members of a mortar platoon in the 5th Cavalry Regiment were found bound and executed. Meanwhile, for the remainder of August there was a marked lull in the action for the Army and Marine units, as the pause would show only 249 deaths along the entire perimeter in eleven days of combat. Air Force and Navy losses during this time amounted to nine aircraft with 11 pilots and crew KIA. August was not done though. On the very last day of the month, August 31st, the Second Battle of the Naktong Bulge would start.

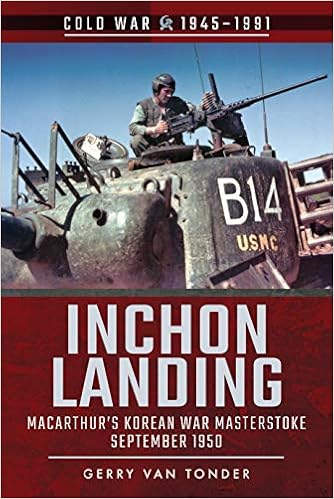

September 1950 - 3474

As we head into September 1950, the Second Battle of the Naktong Bulge is in full swing, and the death toll ever increasing. There were 3474 deaths of U.S. servicemen in September, with the defense of the Pusan Perimeter and subsequent breakout as major contributing factors. During the Second Battle of Naktong, which was another sub-battle of the Pusan Perimeter defense, Task Force Manchu was formed under the 9th Infantry Regiment with the intent of aggressive patrol actions on the Naktong River. With 386 KIA occurring on September 1st alone, and in the subsequent five days another 883 men were killed, this task force, with the 7th Cavalry, 9th, 21st, 23rd, 24th, 27th, 38th Infantry Regiments and various assigned units bore the brunt of battle deaths. The 1st PMB was committed to battle by on September 3rd and 32 Marine KIA are part of the total. The first week of September also saw three F-80Cs, three F51Ds, and a B-26B shot down, with 10 airmen lost. The second and third B-29 losses of the war occurred on subsequent days, along with all 16 of their crew. From September 10-14, there were 355 KIA, almost all U.S. Army with a few USAF pilots lost. The majority of these deaths occurred with the 1st Cavalry Division fighting around the Taegu area near the Pusan Perimeter. This was the beginning of the ‘Naktong Perimeter Breakout’ from around Pusan. The famous Inchon Landings, otherwise known as Operation CHROMITE, with the 1st Marine and 7th Infantry Divisions landing on the west coast were a total tactical surprise and success. No book or writing can accurately show just how much of a success, but looking at the death toll can shed light on it. The landings were so successful it’s hard to understand that on the 1st day, September 15th, there were only 114 total deaths for the day, and out of that number there were only 2 Navy KIA and 18 Marine KIA directly due to the landings, as the rest came from Army units fighting around the Naktong River and Pusan. The 2nd day of the actual landings there were only 9 Marine KIA. 29 total KIA in two days while landing an entire division and attached units while under fire. Yes, Inchon was extremely successful. There were the inevitable aircraft, pilot and aircrew losses during this time, with anther B-29A loss, along with an RF-80A, F4U-4B, F-80C, and an F-51D, two AT-6Fs, and 7 airmen KIA. Marine KIA began to add up starting on the 17th with the drive toward Seoul. This began with overrunning Kimpo Airfield and continued on into the Seoul district of Yongdungpo. The Marines suffered 384 KIA throughout the Battle for Seoul.

While the Inchon Landings received most of the initial publicity, it was the Army fighting during the Naktong Perimeter Breakout that did most of the suffering. The Inchon Landing and Battle for Seoul were not the cause of the majority of KIA in the second half of the month. A plethora of Army units, again almost all part of the breakout from Pusan and the push north-west, were hard fought. The 1st Cavalry, 2nd, 24th, and 25th Infantry Divisions all provided 955 more men to the death toll in small actions around towns, hamlets and areas with names like Haman, Battle Mountain area (in the Sobuk Mountain range, also called Hills 743 and 665) Chindong-ni area, Pugong-ni (Hill 409), Chiryon-ni, Uiryong, Waegwan, Shindo, Chang-dong, Chungam-ni, Myrang, Imjin Mountain, Hansan-dong, Chinju, Kumchon, and a host of others. The Navy also lost men on the 26th after the destroyer USS Brush hit a mine off of Tanchon, with 14 men KIA. There were also aircraft losses for the last ten days of the month, six F4U’s, five F-51D’s, two H03S-1 helicopters, an F7F-3N, AD-4, and a B-26B, with 20 flyers KIA. And sadly another war crime was reported in September, the Taejon Massacre. Reports vary, but between 42 and 60 captured U.S. servicemen, held in the Taejon Prison, were bound and executed by the NKPA.

October 1950 - 490

There were 490 deaths in October 1950. The U.S. Navy started off October 1st with the minesweeper USS Magpie hitting a mine and sinking, with 16 KIA. However, there was a definite lull in the ground war and battle deaths were drastically reduced. Not including June with its six days of combat, October 1950 was the lowest month of 1950 for deaths. The ‘invasion’ of North Korea began on October 9th, led by the 1st Cavalry Division. This breakout was met with light scattered resistance, with only 35 KIA in three days of fighting. On the 12th the U.S. Navy added more numbers to the death toll when two minesweepers, the USS Pirate and USS Pledge, both hit mines off the island of Sin-do in the Wonsan Harbor and sank, with a combined 15 KIA. The Paekchon Ambush occurred on October 13th, with HQ Battery of the 77th Field Artillery Battalion being overrun and suffering 34 KIA. Six of those KIA were POWs who were murdered by their NKPA captors.

A number of unit actions occurred in the second half of the month that kept the KIA numbers small but constant. The newly arrived 65th Infantry Regiment saw its first action, with 12 KIA on October 17th. The war’s first airborne operation occurred on the 20th, with the 187th Regimental Combat Team (RCT) jumping north of Pyongyang. With only 4 KIA on that day, it was a resounding success and caught the NKPA off guard. In ensuing days though the 187th would have another 48 KIA while fighting in the Battle of Yongju. The 1st Marine Regiment fought an engagement on Hill 109, outside of the town of Kojo, on October 27th. A precursor of hill fighting to come in later years, they had 28 KIA. There are two days in October that are worthy of note. The first is October 25th, where there were no deaths of U.S. military personnel in Korea, a truly remarkable thing considering the death toll since June. And the second is October 28th, where a single young U.S. Marine was the only recorded death, being awarded the Silver Star for giving up his life in defense of his position outside of Kojo. Also, throughout October aircraft losses and deaths continued to pile up. Ten F-51D’s, nine F-80C’s, four B-26B’s, four USN and USMC F4U-4’s, a B-29A, C-47, and an AT-6 all were lost with a total of 48 aircrewmen killed.

October and on into November 1950 were also infamous for one more thing; the Tiger Death March. Starting during the last few days of October and on into November, the march north of U.S. POWs began. As the Breakout from Pusan and Inchon Landings sent the NKPA reeling, they hurriedly started moving the POWs who were captured since July north. Many men did not make it, having died on the way in ones and twos, small numbers, and larger groups. There is no definitive total as to the number of prisoners and number of deaths occurring on the march. Reports vary from 700-800 POWs with a conservative 100-plus deaths directly related to the death march. Those who died during the trek died from exposure, wounds during battle and outright murder by their NKPA captors.

November 1950 - 3646

November 1950 would prove to be the month with the most deaths for U.S. forces during the first year, and in fact during the entire conflict, with 3646 dead. The Chinese People's Volunteer Army (CPVA), which was commonly referred to as Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) initially engaged U.S. forces near the town of Unsan North Korea. November 1st saw the U.S. military reach its own ‘high-water mark’ of the war when the 21st Infantry Regiment captured the village of Chonggodo, just south of the Yalu River. CCF patrols then made contact with elements of the 1st Cavalry Division on the same day, who lost 28 men KIA. But this contact did not give U.S. forces any inkling of what was to come next. November 2nd saw a massive clash of armies known as the Battle of Unsan. All but 27 out of the 501 KIA on this date occurred during the battle. The 8th Cavalry Regiment along with the 99th Field Artillery Battalion was overrun and their ranks decimated. ‘B’ Company 2nd Chemical Mortar Battalion and the 5th Cavalry Regiment were also hit hard. Imagine 474 men killed in one day during one battle, almost more than the entire month of October. The CCF entrance into the war changed forever any outcome that anyone could envision. While the Battle of Unsan was going on, other smaller actions in other locations continued. The 7th Marine Regiment was engaged in the Majon-Dong-Sudong area, losing 51 KIA in two days fighting on and around Hill 532. The 19th Infantry Regiment lost 100 KIA on 4-5 November while fighting on Hill 123 northeast of Anju along the Chongchon River. And on November 6th, the 27th Infantry Regiment lost 28 KIA from a guerilla ambush in the hills around the Kumchon-Sibyon-Ni area. In the skies over Korea the first all-jet combat in history occurred with an F-80 shooting down a Mig-15 on November 8th. However that didn’t stop aircraft losses from continuing to rise, with a total of 33 pilots and aircrew losing their lives during the first two weeks of the month. This number includes two more B-29s with a combined loss of 11 crewmen. Yet another ambush, this time by the NKPA, killed 43 men of the 24th Infantry Regiment near Yonchon on the 11th. Through the middle of the month, combat actions slowed and were very light, but this was about to change drastically on November 25th when a large CCF counter-offensive crashed into the UN lines causing the majority of U.S. deaths for the month and year in the ensuing days. The 1st Marine, 2nd, 3rd, 7th, 24th and 25th Infantry Divisions are all hit extremely hard by the CCF onslaught. And thus began the Battle of the Chongchon River, which was the initiation phase that would lead to the eventual Battle of the Chosin Reservoir. 2335 men were killed or captured (and subsequently died or murdered) in the last five days of November 1950. The number is staggering. 1264 Soldiers were KIA in three days of holding actions along the Chongchon River, November 26-28. Regimental Combat Team-31, otherwise known as Task Force Faith/Maclean, which was formed out of the 7th Infantry Division to protect the Marine’s right flank at Chosin, was decimated with 247 KIA, another contributing factor to the total dead. There was a slight slowing in the fighting on the 29th, although Task Force Drysdale, a multi – service task force of Marine, Army and UN units, added over a 100 deaths to the lists. And then 793 dead on November 30th, which has the inglorious distinction of being the single most deadliest day of the Korean War. This is when the struggle at the Chosin Reservoir began in earnest.

There are two things of note about the last week of November that should be recognized. The numbers of these recorded deaths include men who were captured and subsequently died while in captivity. The way the U.S. Military tracked and reported its numbers necessitated that the date of capture or wounded would be used as the initial date of loss. A prime example of this would be the 38th Field Artillery Battalion, which lost 214 dead while running the Kunu-ri Gauntlet (also referred to as the Battle of Kunu-ri) along the Chongchon River. A vast majority of this number were actually captured by the CCF, but died while in captivity, hence November 30th is their reported date of death. And secondly, while the Chosin Reservoir is recorded as one of the greatest battles in the annals of the USMC, it should also be remembered that the majority of battle deaths during this time were sustained by U.S. Army units.

December 1950 - 2337

The beginning of December 1950 saw the Battle of Chosin Reservoir in full swing and contributed the vast majority of deaths during this last month of the year. There were 2337 deaths in December, and 1496 occurred in the first two days alone. 765 KIA on December 1st and 734 KIA on December 2nd. The 9th and 38th Infantry Regiments, along with the 82nd AntiAircraft Artillery, 2nd Engineer Combat, and 503rd Field Artillery Battalions ran the Kunu-ri Gauntlet and were cut to pieces, while on the eastern shore of the Chosin the 15th Anti-Aircraft Artillery and 57th Field Artillery Battalions, along with the 31st and 32nd Infantry Regiments were paying their price in blood. Air operation losses were light during the first week of the month, with three B-26Bs, two F4U’s, a F-51D, RF-80 and an RB-45C lost and 16 airmen dead. December 6th is another perfect example of the ‘fog of war’ and just how hard it is to track personnel losses while in combat. The 57th Field Artillery Battalion, finally reconstituting and counting heads, identified another 85 artillerymen as KIA on the 6th, although they more than likely were killed on 1-2 December. As the fighting in and around Chosin subsided, the Marines were still taking losses there, losing 157 on December 6th thru 8th around the towns of Hagaru-ri and Koto-ri, and hills North, Fox and 1081. The second week of December showed a marked decrease in combat operations, both with UN forces and with the CCF as the Korean winter settled in. Death still occurred though, now in small numbers as winter positions became fortified and solidified. On December 15th, 34 men from Task Force Dog were lost while covering the Hamhung escape route from Chosin to Hungnam Harbor. None of their bodies were ever recovered.

Very small engagements continued with small numbers of KIA occurring each day for the rest of the month, slowly adding to the total. The remainder of December 1950 left many wondering what 1951 would bring. And daily death was a constant thought and affected all ranks. Case in point on December 23rd, General Walton Walker, commanding general of the U.S. 8th Army in Korea, was killed in a traffic accident while returning to his HQ from a meeting. And a day later, on Christmas Eve 1950, an enemy shore battery engaged the destroyer USS Ozbourn off of Wonsan, killing 1 seaman. No one wishes to die on Christmas Day, but during wartime it is inevitable. 1 KIA and 1 DOC occurred on the 25th. From the 26th through the 29th, while ground combat became less and less possible, the air war continued. Seven aircraft losses, four F-80Cs, an F9F, and two B-26s, with their corresponding 12 crewmen KIA. And lastly, on New Years Eve 1950, 10 infantrymen lost their lives to close out the first year of fighting in Korea.

| * * * |

Author Notes: This article concentrates on the United States involvement in the Korean War and does not include the number of United Nations (UN) and Republic of Korea (ROK) forces killed. There are many ways to review, interpret, and present statistical data such as this, and there have already been a number of books written with tallies of KIA for either battles, dates of battles or units that fought those battles. This article takes a different approach. The main source for the numbers quoted in this article is the Korean War Project which maintains a digital file of all deaths that occurred associated with Korea by date, unit, and location. This digital file is the most comprehensive source available, compiled from numerous sources, namely the TAGOKOR, DIOR, PMKOR, NARA, and respective service documentation.

• TAGOKOR File - The Army Adjutant General's Office Korean War Casualty File

• DIOR File - The Directorate for Information Operations and Reports File

• PMKOR - The Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) Personnel MissingKorea File

• NARA RG 330 - National Archives and Records Administration Records Group 330, Records of the Office of the Secretary of Defense

• Service records of the U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy Numerous disparities have been found in documentation from different sources, and this is to be expected. There is no definitive Korean War death list. This article is based on the reported and recorded deaths per day per unit.

Other Reference:

• Korean War Project www.koreanwar.org

• Korean War Educator www.koreanwar-educator.org

• Veterans of Foreign Wars publication: ‘Battles of the Korean War 1950-1953’

• Book: South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu – By Roy E. Appleman, published 1961

• Internet sources such as Wikipedia and various search engines to verify proper spellings and locations of towns, cities and geographical areas of importance, aircraft and ship identifications, and the cross-referencing of units and dates throughout the year

• Various Command Reports and Unit Daily Journals

| * * * |

© 2026 Anthony J. Sobieski

Published online: 07/20/2019.

About the author:

Anthony Sobieski is a Department of Defense employee and retired U.S. Air Force reservist. He is a recognized Korean War historian and author, having published three books on the subject; FIRE MISSION! (2003), FIRE FOR EFFECT! (2005), and A Hill Called White Horse (2009).

* Views expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily represent those of MilitaryHistoryOnline.com.